Famous landmarks that were almost destroyed

Saved from the brink

Skylines and landscapes around the world would look pretty empty without their famous monuments. But some of the planet's most distinguished landmarks almost didn't stand the test of time.

Click through the gallery to discover the beloved attractions that were nearly lost over the centuries...

London Eye, London, England

The London Eye was dreamt up in the 1990s by husband-and-wife architect team David Marks and Julia Barfield, as part of a competition for a monument to mark the millennium. The competition didn’t bear fruit, but the architects decided to take the project forward themselves.

Construction of the now-famous London landmark began in 1998. It’s pictured here in 1999, laying horizontally across the River Thames, ready to be lifted into position.

London Eye, London, England

When the landmark opened to the public in 2000, it quickly became a beloved fixture of the London skyline and one of the capital’s top attractions. But the temporary observation wheel was due to be dismantled five years after it was installed.

However, such was its appeal that Lambeth Council granted permission for the wheel to become a permanent attraction. More than three million people enjoy the views from the revolving pods each year.

Love this? Follow us on Facebook for travel inspiration and more

Sponsored Content

Hollywood Sign, Los Angeles, California, USA

The Hollywood Hills would look rather bare without the world-famous sign, but the tall white letters were only meant to be there temporarily. The sign, which originally read 'Hollywoodland', was erected to mark a new housing development in the 1920s.

Its creators only intended the letters to stand for 18 months. But a century later, the Hollywood Sign remains one of California’s most distinctive landmarks.

Hollywood Sign, Los Angeles, California, USA

Despite becoming a glittering symbol of Hollywood, the sign (which lost its 'land' in 1949) fell into disrepair. It continued to deteriorate right up until the late 1970s when the wooden letters were replaced with metal.

Now, it’s impossible to envisage Los Angeles without this iconic sign nestled in the Hollywood Hills.

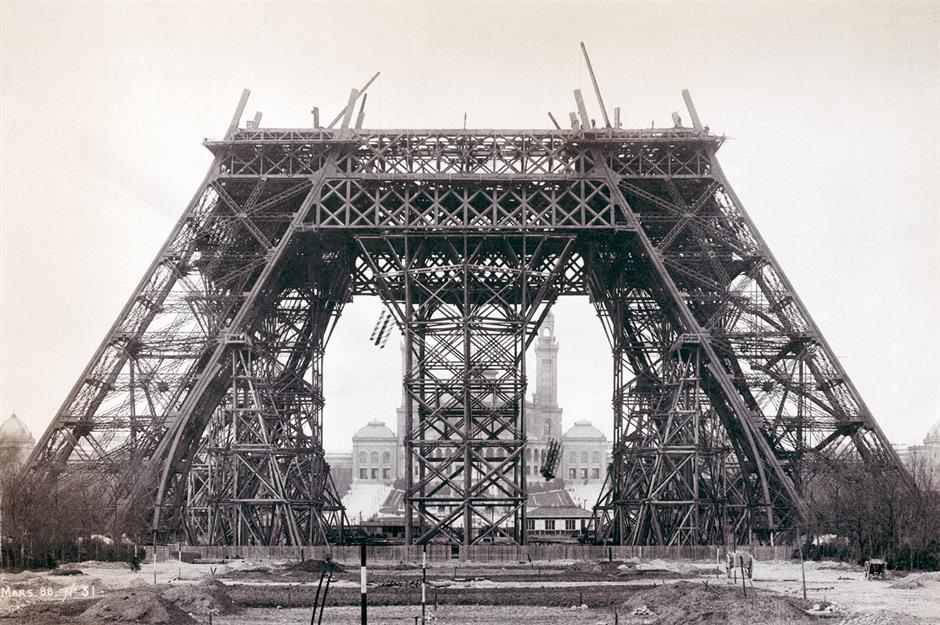

Eiffel Tower, Paris, France

It’s hard to imagine the Paris skyline without the Eiffel Tower, but the landmark was originally intended to be a temporary installation. It was built for the International Exposition of 1889, serving as the impressive gateway to the show, with the tower itself soaring to 984 feet (300m).

It was due to be pulled down in 1909, which would have given it a 20-year lifespan.

Sponsored Content

Eiffel Tower, Paris, France

In a bid to save the tower, architect and civil engineer Gustave Eiffel waxed lyrical about the landmark’s potential uses in the fields of science, technology and meteorology. He described it as an “observatory” and a “laboratory the likes of which has never before been available to science”.

The city eventually conceded, and the tower was used for meteorological and astronomical experiments. Today, of course, it’s an iconic tourist attraction visited by millions each year.

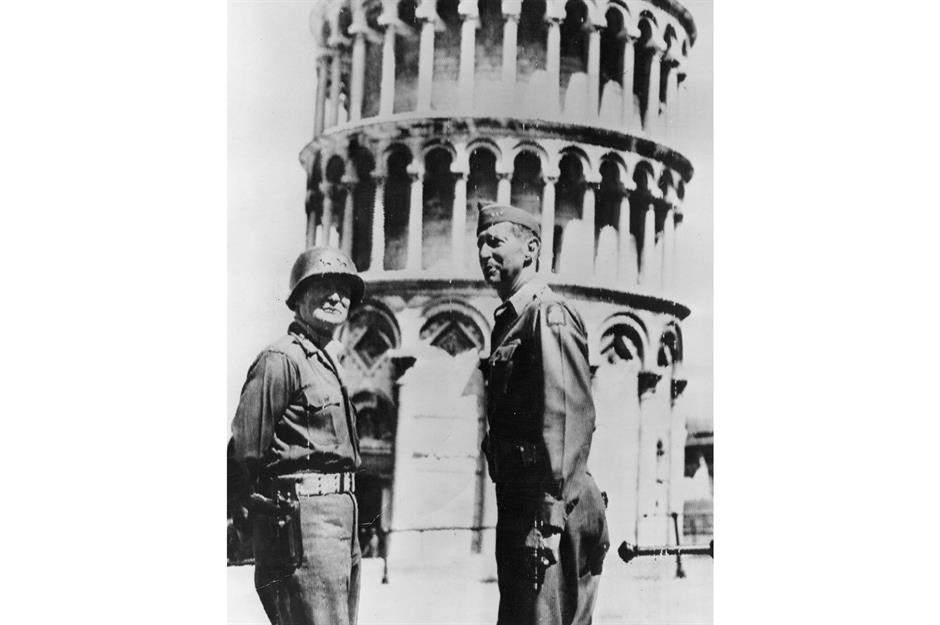

Leaning Tower of Pisa, Pisa, Italy

The Leaning Tower of Pisa is a feat of medieval architecture and a symbol of one of Italy’s prettiest cities. But its life was almost cut short during World War II.

Leon Weckstein, a GI in the United States Army, was under orders to demolish the beautiful tower, if necessary, due to fears it was occupied by German forces. The tower’s future hung in the balance. It’s pictured here in 1944, after the undamaged tower had been taken by the Allies.

Leaning Tower of Pisa, Pisa, Italy

Upon reaching the target, Weckstein was captivated by the tower. In fact, he was so entranced that he found he could not go ahead with the orders to demolish it.

In his memoir, Through My Eyes, Weckstein wrote, “The tower, the neighbouring cathedral and baptistery, were too beautiful”. As he stood enraptured, German shells began to fall, the American soldiers fled, and the tower was spared.

Sponsored Content

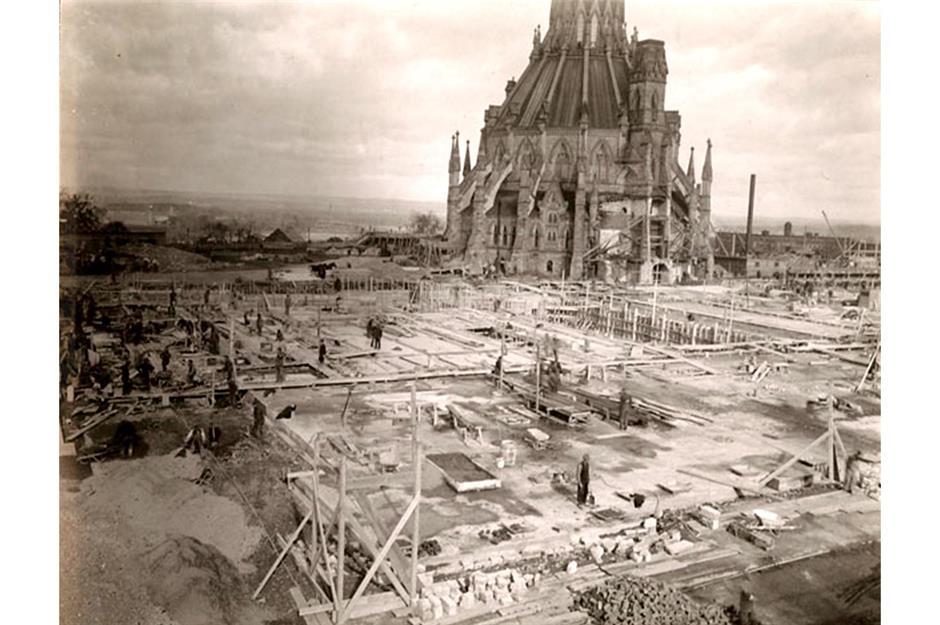

Library of Parliament, Ottawa, Canada

Crowning Ottawa’s Parliament Hill, this rotund Gothic building dates to 1876 when it was built as part of the Parliament of Canada’s sprawling Centre Block. The stunning library has stood the test of time, surviving a blaze in 1916 which ravaged the rest of the parliamentary complex.

The library is shown in the background of a photograph from 1916, rising from the wreckage as construction work begins on the rest of the complex.

Library of Parliament, Ottawa, Canada

The fire, started by sparks in a wastepaper basket, swept through the buildings, destroying almost everything in its wake. However, against the odds, the Library of Parliament was saved as its mighty iron doors were closed.

The other buildings were rebuilt by 1927. Today, they still stand proudly in Canada’s capital, with the library the site’s crowning jewel.

Cologne Cathedral, Cologne, Germany

Cologne Cathedral dates to the 13th century, although much of it was constructed during the 1800s. But it almost didn’t survive the 20th century. Cologne was hit hard in World War II, with buildings razed to the ground and the city centre devastated.

The cathedral wasn’t spared. It reportedly took 14 bomb hits during the war, with its lofty spires a useful reference point for the Allied Forces. Here, the cathedral is seen amid the flattened city in 1945, as US troops move through the ruins.

Sponsored Content

Cologne Cathedral, Cologne, Germany

Although the cathedral suffered extensive damage – including holes in its walls and spires and shattered stained glass – it remained standing. Much of the artwork and sacred relics inside were protected, and the cathedral was eventually restored.

Today, it’s one of Germany’s most-visited attractions. With its soaring twin spires, it remains one of Europe’s most impressive cathedrals.

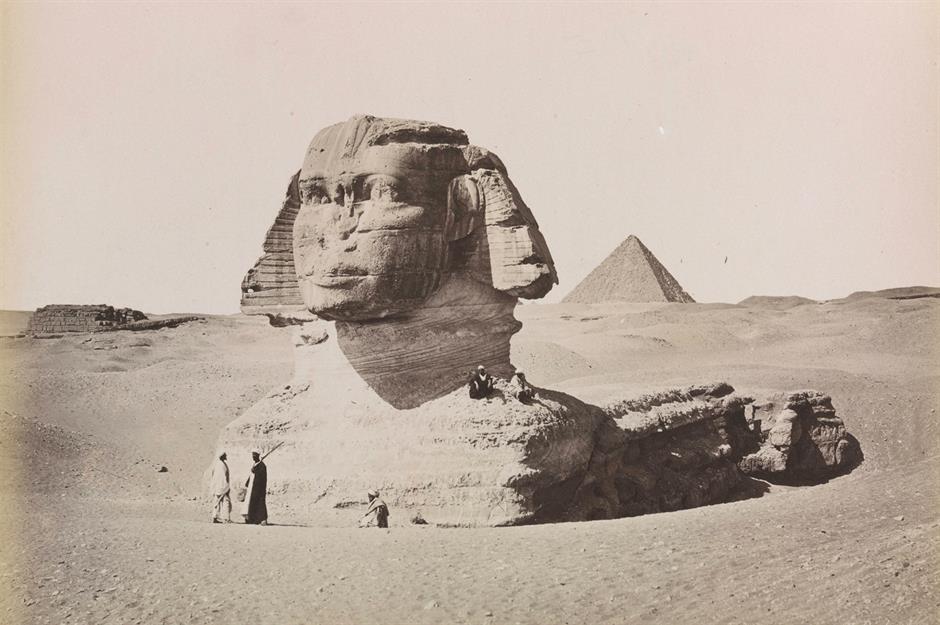

Great Sphinx of Giza, near Cairo, Egypt

Part of the Giza pyramid complex (whose Great Pyramid is one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World), the Sphinx is a mammoth limestone monument of a mythical creature with a human’s head and a lion’s body. It’s thought the statue was built around 2500 BC for King Khafre and it’s on many a traveller’s bucket list.

However, it was almost lost to the whims of Mother Nature. It’s pictured here circa the 1870s, buried to its shoulders by desert sands.

Great Sphinx of Giza, near Cairo, Egypt

At some point during its long history, the Sphinx was abandoned. Early attempts to excavate the landmark were unsuccessful and its figure had suffered serious erosion.

It wasn’t until the 20th century that the ancient monument was finally completely excavated, saving it from further damage and revealing it as one of the largest monolithic statues in the world.

More of the world's landmarks under threat from climate change

Sponsored Content

Grand Central Terminal, New York City, New York, USA

Grand Central in New York opened in 1913 and has been a beloved Midtown Manhattan landmark ever since. It serves as both a railroad terminal and a shopping and dining complex and is known for its elegant four-faced clock and buzzing main concourse.

It’s pictured here during its construction in 1912. The building attracts hundreds of thousands of people per year, but it almost didn’t last past the 1960s.

Other incredible images of famous tourist attractions under construction

Grand Central Terminal, New York City, New York, USA

Long-distance rail travel took a hit after World War II and the station fell into decline. Neglected and decaying, the once opulent building faced the wrecking ball in the 1950s and 1960s.

However, it was eventually saved by campaigners, including former First Lady Jackie Kennedy Onassis, and granted landmark status by 1976. In the decades that followed, it was restored and once again took on the glittering shape we see it in today.

Dome of the Rock, Jerusalem

The Dome of the Rock, with its giant golden dome and intricate mosaics, dates to the 7th century. The site it’s built upon is sacred to both Jewish and Muslim peoples.

The building has suffered a tumultuous history, taking several blows from Mother Nature and being reimagined multiple times throughout its existence. It's pictured here in the 1920s before the 1927 Jericho earthquake.

Sponsored Content

Dome of the Rock, Jerusalem

The sacred building was also damaged in a pair of earthquakes in the 9th century and again in the 11th century, when its mighty dome was destroyed. But each time, the shrine has been restored and rebuilt.

Extensive renovations took place in the 1990s and it remains an important pilgrimage site for people across the globe.

Anne Frank House, Amsterdam, Netherlands

This unassuming canal-side house in Amsterdam was made famous by Anne Frank, a young Jewish girl who hid in a secret annex with her family during the Nazi regime and kept a diary of her experiences. Although Anne didn’t survive the war, her diary was preserved and later published.

This image from 2017 shows the room she occupied, as preserved by the Anne Frank Foundation.

Anne Frank House, Amsterdam, Netherlands

After World War II, the building faced an uncertain future, and it looked likely that it would be demolished to make room for a factory. However, campaigners fought to preserve the building on account of its important wartime history and, happily, they were successful.

By the mid-1950s the house had been saved. In the 1960s, it opened as a public museum, as it remains today.

Sponsored Content

Colosseum, Rome, Italy

One of the world’s most famous Roman monuments almost didn’t survive into this century. The life of this giant amphitheatre, famed for its bloody gladiatorial battles during the Roman era, has spanned around two millennia. But major earthquakes over the centuries have threatened to pull this ancient landmark to the ground.

One in 1349 caused its south side to collapse. In 1703, the landmark was rocked again by another earthquake that affected the Abruzzo region. It’s captured here in a 1747 painting, several decades after the second disaster.

Colosseum, Rome, Italy

More recently, in 2016, a devastating earthquake struck Rome and wider Italy once again, forming further cracks in this fragile ancient landmark. But for now, the amphitheatre still stands tall against the odds, drawing visitors in their millions each year.

Sydney Opera House, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia

This landmark nearly didn’t see the light of day at all. Construction began in March 1959 but initial hopes the venue would open its doors in January 1963 (on Australia Day) were quickly dashed.

Among the problems were architect Jørn Utzon’s bold and somewhat underdeveloped design, spiralling costs and construction headaches, in part due to the innovative curved roof surfaces. All of this meant that by the original opening date, only the podium would be completed.

Sponsored Content

Sydney Opera House, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia

The problems and delays led to political pressure to scrap the project, as the costs continued to rise. In 1966, Utzon resigned – leading to a public outcry.

Following the architect’s departure, a new team was brought in to redesign the opera house's interior. This only piled on the costs, as parts of the existing structure had to be demolished or adapted. It finally opened in October 1973, a mere 14 times over budget.

Forbidden City, Beijing, China

Once a home for China’s imperial rulers, Beijing’s Forbidden City sprawls across 178 acres and today houses the Palace Museum. It’s also the largest collection of ancient wooden structures in the world.

Yet, it was almost lost forever, as fire has threatened to completely ravage the historic complex on more than one occasion over the centuries.

Forbidden City, Beijing, China

The Forbidden City suffered extensive damage in 1644 when it was captured by Chinese rebel leader Li Zicheng and his forces. Zicheng was quickly overthrown by Manchu invaders, but he set fire to large swathes of the imperial complex as he fled.

Much of the structures were rebuilt throughout the Qing dynasty. It has been a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1987.

Sponsored Content

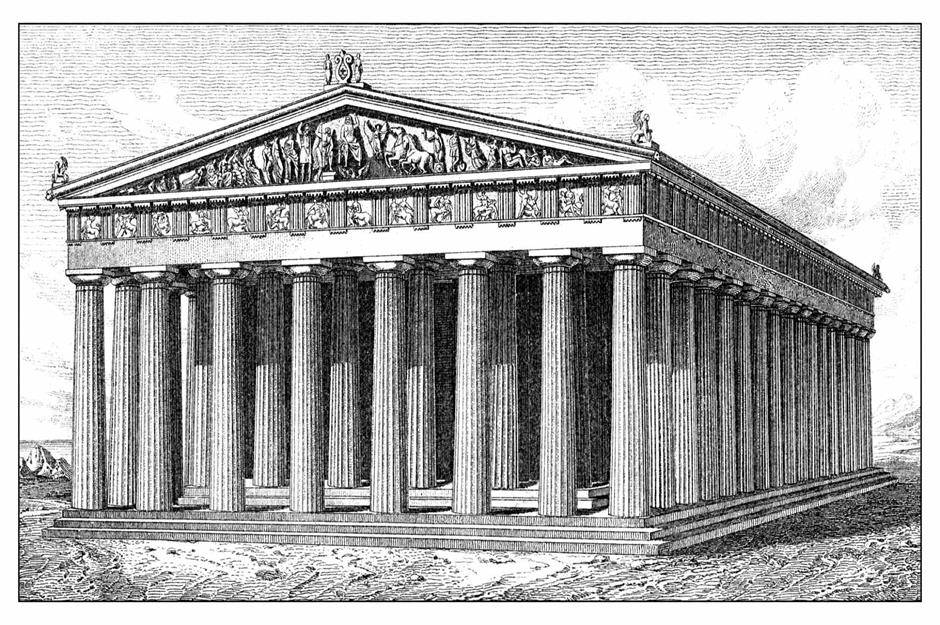

Parthenon, Athens, Greece

It’s one of the world's most recognisable archaeological sites but the Parthenon almost succumbed to a bombardment in 1687 by the Venetians. Part of a larger siege of the Acropolis at Athens, the strikes came amid a war with the Ottoman Empire over control of the Greek islands and territories.

The bombardment partially destroyed the temple, which was built between 447 and 438 BC. It led to a long period of neglect.

Parthenon, Athens, Greece

A large-scale restoration project finally began in 1975, and the Acropolis became a protected UNESCO World Heritage Site 12 years later. However, it faces continuing threats from extreme weather events and tourists – which number around two million each year.

Work to restore the Parthenon to its original state is ongoing, ensuring this historically important site is not lost for future generations to appreciate.

St Paul’s Cathedral, London, England

St Paul’s Cathedral, with its titanic dome and elegant columns, took its present shape in the 17th century, designed by lauded English architect Christopher Wren. Earlier iterations were destroyed by Viking Raiders and later Cromwell’s cavalry during the English Civil War of the 1600s.

Work on the cathedral had lasted from 1675 to 1710. But it was almost destroyed once again during World War II. It's pictured here surrounded by smoke in 1940.

Sponsored Content

St Paul’s Cathedral, London, England

The cathedral took several direct hits as bombs shook London during the Blitz, but it miraculously stayed standing, becoming an emblem of resilience and wartime resistance. Once the conflict was over, St Paul’s was restored to its former glory and was a site of post-war celebration.

Now, the cathedral attracts millions of visitors per year and has hosted important events, including preaches by Dr Martin Luther King Jr and the marriage of Prince Charles and Diana.

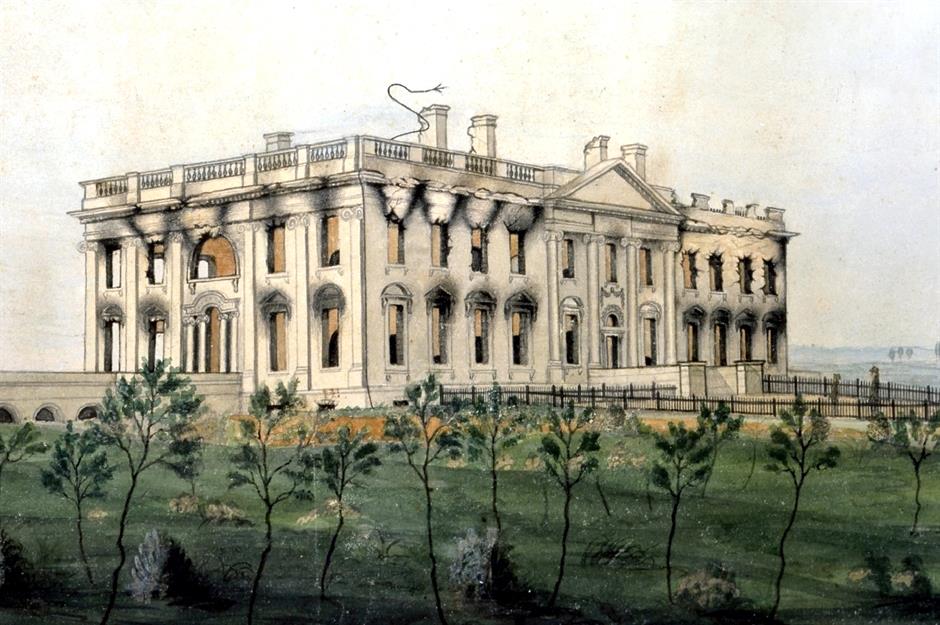

The White House, Washington DC, USA

The world’s most famous presidential building, the White House has been home to America’s president since 1800, when John Adams first moved into the unfinished residence with his wife. But it was almost completely destroyed in 1814.

During the War of 1812, the British stormed Washington DC, burning several federal buildings, including the White House, forcing then-president James Madison to flee the city.

The White House, Washington DC, USA

Following the devastation, the White House was reconstructed by James Hoban, the Irish-born architect who originally designed the building. Hoban had the residence ready for President James Munroe by 1817, and his ongoing reconstruction included the addition of the North and South porticos in the 1820s.

Along with the Capitol Building, the White House remains the most recognisable symbol of the American government.

Sponsored Content

United States Capitol, Washington DC, USA

The Capitol Building in Washington suffered a similar fate during the War of 1812. It too was set alight by the British during the Burning of Washington in 1814 and was left almost completely devastated.

This painting by American artist George Munger features the mighty building in the aftermath of the blaze. It shows the blackened walls and the hollow shell of the rotunda without a façade or a roof.

United States Capitol, Washington DC, USA

At the time of the fire, the Capitol Building was still only partially completed but, luckily, the use of fireproof materials prevented the landmark’s complete collapse. One of the building's original architects, Benjamin Henry Boneval Latrobe, was rehired to restore it in 1815 (he was eventually succeeded by Charles Bullfinch). The work would take around four years.

The building we see now took shape in the mid-1800s, when its mammoth cast-iron dome was erected.

Now discover what the world's most famous landmarks looked like a century ago compared to today

Comments

Be the first to comment

Do you want to comment on this article? You need to be signed in for this feature