Amazing archive photos show café culture through the years

100 years of coffee, conversation and culture

Explore the salons, tiled bistros and bustling shop counters that have defined café culture for more than 100 years. From the literary cafés of Paris and Vienna’s grand coffeehouses to bohemian haunts in Prague and vibrant NYC diners, these evocative photos capture how cafés became cultural institutions. More than just places to sip espresso, they were hubs of reflection, romance and revolution.

Click or scroll through this gallery to travel back in time, and pour yourself a cup...

c.1890: A café with games in Vienna, Austria

This suburban coffeehouse in the district then known as Rudolfsheim captures the quiet elegance of Viennese café culture at the turn of the century. The café offered its patrons a billiards table as well as a familiar place to linger over coffee, read the paper or exchange gossip.

These neighbourhood cafés were the everyday counterpart to Vienna’s grand coffeehouses, and were equally essential to the city’s social rhythm.

1890: The playroom of Vienna's Café Eckl

This photo shows the ‘playroom’ in Café Eckl, a classic case study for Vienna’s storied coffeehouse tradition. Located in the Neubau district, it opened in 1802 and served wealthy locals for over a century.

With billiard rooms, a reading salon and an English-style garden, it offered more than just coffee – it was a space for leisure, lifestyle and conversation. By the 1890s, cafés like Eckl were central to Viennese life, laying the foundation for the intellectual and artistic café culture that would flourish well into the 20th century.

Sponsored Content

c.1890: The legendary Café de la Paix in Paris

An icon of Parisian elegance, the Café de la Paix stood at the heart of the Grands Boulevards, attracting opera-goers, artists and aristocrats. Opened in 1862 beside the Grand Hôtel, its opulent Napoleon III interiors made it a landmark of the Belle Époque – a period of peace and artistic and scientific flourishing in France between 1871 and 1914.

By 1890, the café's regulars included French novelist Émile Zola, Russian composer Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky and the Prince of Wales, later King Edward VII, drawn by its proximity to the Palais Garnier opera house.

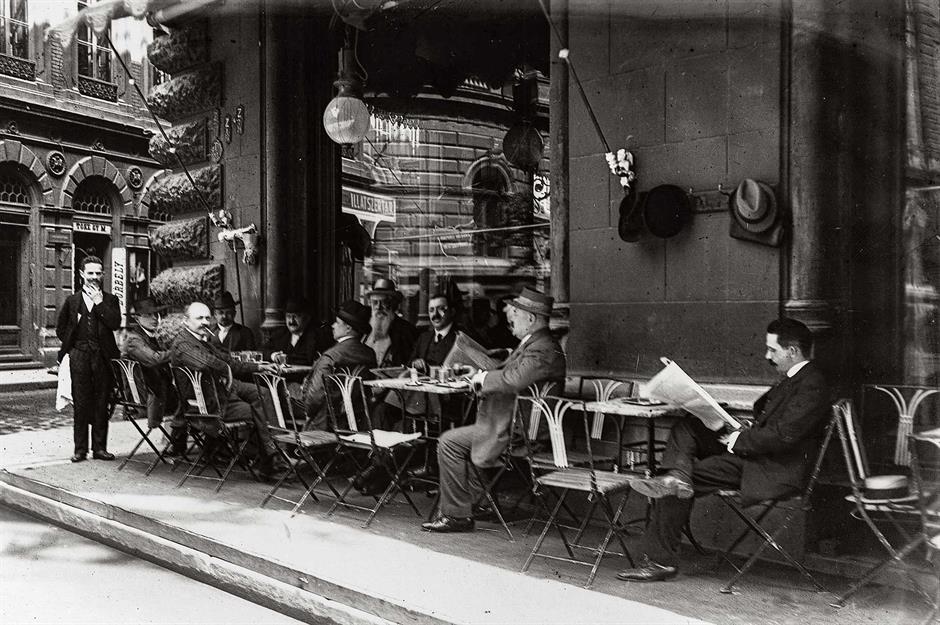

c.1890: Parisian alfresco elegance

Set in the leafy Bois de Boulogne park, Le Pré Catelan was one of Paris’s most fashionable outdoor cafés during the Belle Époque era. Housed in a pavilion built during the reign of Napoleon III, it offered a serene escape from the city’s bustle. On warm afternoons, Parisians gathered beneath the trees to socialise over coffee and ice cream, embodying the spirit of leisure and sophistication associated with the period.

c.1900: A whimsical escape in Montmartre

The Jardin de Paris at the infamous Moulin Rouge nightclub featured a striking giant stucco elephant, purchased from the 1889 Paris World's Fair. Guests could ascend a spiral staircase inside the elephant’s leg to reach a unique performance space, where belly dancers entertained patrons in the torso of the animal.

This alfresco café quickly became a lively hotspot where Parisian society mingled, enjoying bold spectacle and vibrant nightlife in the heart of Montmartre, which was quickly becoming the city's most artistic and bohemian neighbourhood.

Sponsored Content

c.1900: Lyons tea shops in London

From the late 19th century onwards, Lyons tea shops became a beloved fixture across the UK, offering affordable, accessible refreshment in stylish surroundings. The first shop opened in Piccadilly, London around 1894, with roughly 200 more proceeding to open nationwide.

Staffed by efficient waitresses who were affectionately known by the name 'Gladys', these cafés were vital social hubs where Londoners and tourists enjoyed quality tea, light meals and a welcoming atmosphere amid the bustle of the city.

c.1904: Elegance and empire in Havana, Cuba

This opulent Havana café reflects the city’s status as a cosmopolitan hub under Spanish and then US influence. Such spaces were typically reserved for Cuba’s super-rich, foreign visitors and businessmen, offering refined service and European-style interiors.

The country’s elite had made a fortune in the sugar industry but for the majority of ordinary Cubans these venues remained out of reach. Many sugar workers lived on – and below – the breadline, helping sow the seeds for Fidel Castro’s Cuban Revolution in the 1950s.

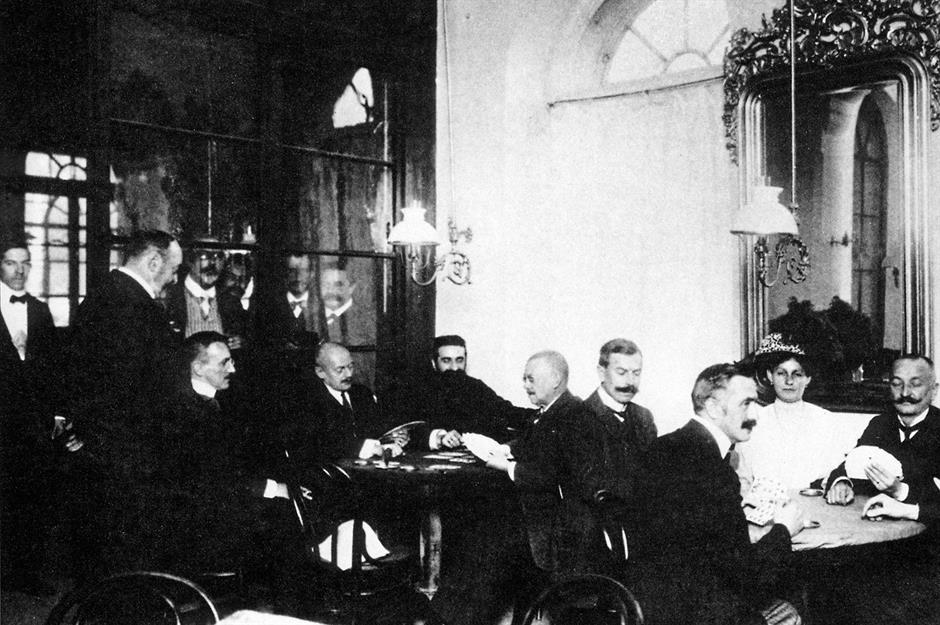

c.1910: Intellectuals gather in Budapest, Hungary

Opened in 1887, Central Café quickly became a cultural and political hotspot in Budapest’s Belváros district. Renowned for its modern architecture and elegant décor, it attracted university students, writers and activists who gathered to debate ideas and forge social movements.

Around 1910, the café was a key meeting place for Hungary’s intellectual elite and political groups. Within a few years of this photo being taken, the outbreak of World War I would bring drastic changes for Budapest and its citizens.

Sponsored Content

1912: The Veranda Café on the Titanic

The Veranda Café and Palm Court aboard the RMS Titanic marked the height of early 20th-century luxury and elegance at sea. Opened in 1912, this lavish space provided first-class passengers with a serene setting to relax amidst exotic palms and stylish décor. The Titanic’s public rooms embodied the optimism and grandeur of the Edwardian era, a brief moment of spectacle before the ship’s tragic maiden voyage.

1913: Uncertainty mounts at a café in Bulgaria

Captured the year before World War I, this scene in Kutlowitsa (now known as Montana) offers a rare glimpse into everyday life in early 20th-century Bulgaria. In 1913, the country had just emerged from the Balkan Wars, which reshaped borders across the unsettled region. Cafés like this one were essential social spaces, where men met to discuss politics, share news and find a sense of normalcy amid the upheaval.

1941: Coffee before takeoff in Washington, D.C.

This quiet airport café scene was captured in July 1941, just months before the US entered World War II. As commercial aviation expanded, airport eateries offered a new kind of public space: modern, mobile and democratic.

Travellers and service staff gathered over coffee and light meals in between arrivals and departures. At Washington, D.C.’s municipal airport, such spaces reflected a nation on the move, hovering between peacetime routine and the coming upheaval of war.

Sponsored Content

1943: A taste of normality in Sweden

During World War II, Sweden remained neutral, but not untouched. Food shortages and rationing meant sugar and coffee were strictly limited - yet the tradition of 'fika' endured. This ritual sharing of coffee and cake remained a cherished cornerstone of Swedish life, and locals queued eagerly in cafés like this one for a rare moment of everyday joy, even in austere times.

In much of the rest of Europe at this time, scenes like this were rare.

c.1950: Post-war calm in England, UK

Fresh daffodils and patterned wallpaper add cheer to this modest tearoom, where a mother and her children stop for a quiet moment.

In post-war Britain, cafés like this served a vital social role. As rationing on tea, sugar and other foodstuffs gradually ended and towns recovered from wartime damage, tearooms became affordable spaces for families and women to meet, rest and enjoy simple pleasures.

1959: Outdoor café culture in Belgrade, Yugoslavia

By the late 1950s, Belgrade’s café culture flourished in a unique post-war setting. The city was the capital of Yugoslavia, an Eastern European nation which, under the regime of socialist dictator Josip Broz Tito, had broken from the Soviet Union and embraced a more independent path.

Street cafés like this became popular urban spaces for men and women to socialise, read and watch the world go by. In a city balancing socialist ideals with Western influences, coffee culture could offer both connection and quiet defiance.

Sponsored Content

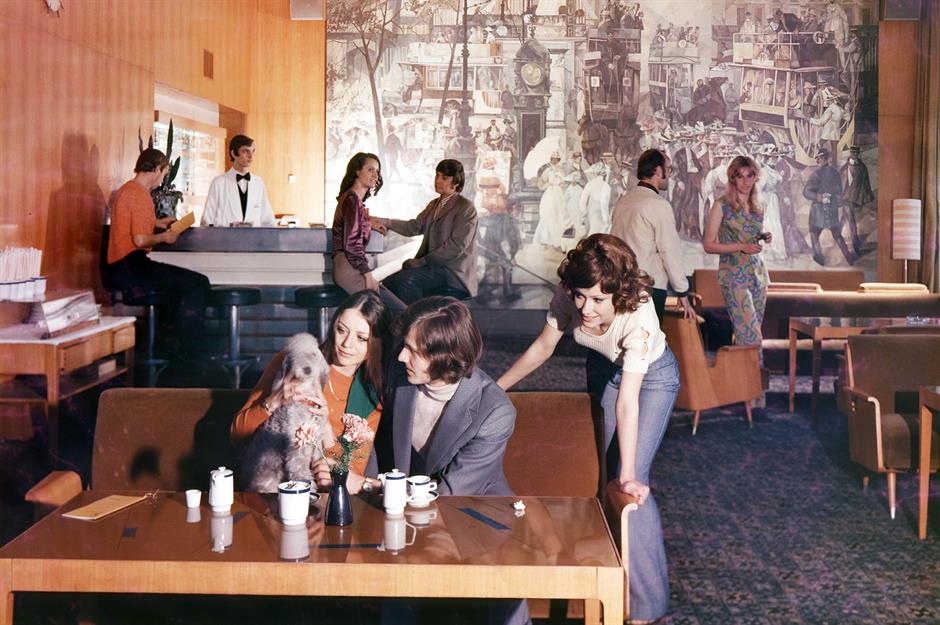

1972: A café beyond the wall in East Berlin

Germany and its capital, Berlin, were partitioned after World War II, and in the socialist, Soviet-aligned east, cafés could be relaxed social spaces in an otherwise ordered world. By 1972, daily routines in East Berlin unfolded under tight state surveillance behind the Berlin Wall, but cafés like this one continued to offer conversation, connection and quiet escape.

Coffee could be in short supply – often rationed or replaced by questionable substitutes – but the ritual of meeting over a cup remained deeply valued, an ordinary act that carried significance in a restricted society.

1987: Night owls in NYC

The Lone Star Café, captured here in 1987, was a downtown New York institution known for legendary country music performances and the huge iguana on its roof. Located at 13th Street and 5th Avenue, it drew a mix of rock stars, politicians and late-night regulars.

By the late 1980s, New York's café scene was a microcosm of the city itself. From diners to coffee bars and music venues, cafés were energetic, evolving places and served as spaces where artists, professionals and night owls crossed paths.

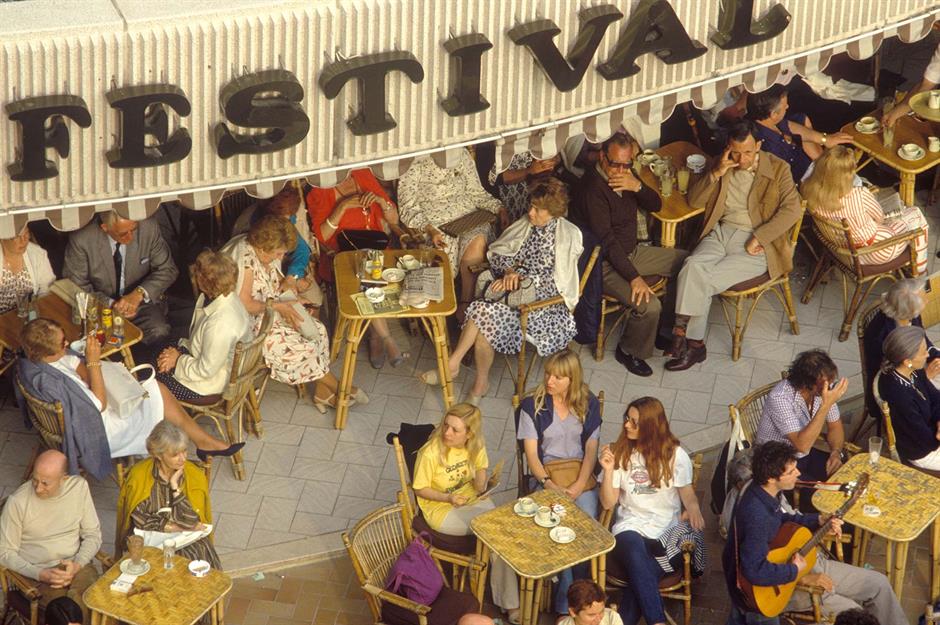

1980: Sun, style and cinema in Cannes, France

Set beside the Palais des Festivals, the Festival Café in Cannes offered tourists a front-row seat to Riviera glamour. By 1980, the city was firmly established as an international hotspot, thanks to the Cannes Film Festival and a legacy of jet-set appeal.

Cafés like this became part of the spectacle where visitors could sip drinks and people-watch under the Mediterranean sun.

Sponsored Content

1989: A proper London cuppa

At Peter’s Café in Chelsea, London taxi drivers are pictured here on a break in 1989. Traditional cafés like this remain an essential pit stop for the city’s black cab drivers, providing a place to swap stories, catch up on the day’s news and refuel between fares.

Known as 'greasy spoons', they offer classic dishes like full English breakfasts or fish and chips, washed down with cups of tea served from a steaming urn on the counter.

1989: Coffee and change in Prague, Czechoslovakia

As the Velvet Revolution gathered momentum in Czechoslovakia – one of several revolutions across Eastern Europe that accompanied the collapse of the Soviet Union – Prague’s cafés became havens for activists and intellectuals. Long central to the city’s cultural life, these spaces once again became sites of quiet resistance and shared purpose, as peaceful protest led to the fall of communist rule.

Comments

Be the first to comment

Do you want to comment on this article? You need to be signed in for this feature