The fascinating history of America's hidden empire

From colonists to colonies

America has always thought of itself as a republic – not an empire. Founded on ideals of liberty, America has spent much of its history fighting against empires: the British in 1776, Hitler's thousand-year reich, and the so-called "evil empire" (as Ronald Reagan famously termed the Soviet Union). But there's plenty of imperialism in America's past too – first in North America and then across the world.

Click through this gallery to go on a chronological journey through the surprising story of American empire…

Concept versus reality

'American empire' can be a slippery phrase. Today it is often used to describe a sort of abstract empire: the global reach of the American economy, the cultural influence of American music and movies, and the political effects of America’s superpower status.

But less often discussed is the literal empire that America had and partly still has: the rapid annexation of hundreds of millions of acres of Native American lands, the steady accumulation of islands across the Caribbean and Pacific, and the occupation of larger colonial possessions such as the Philippines. This gallery will track America's territorial empire – at home and abroad.

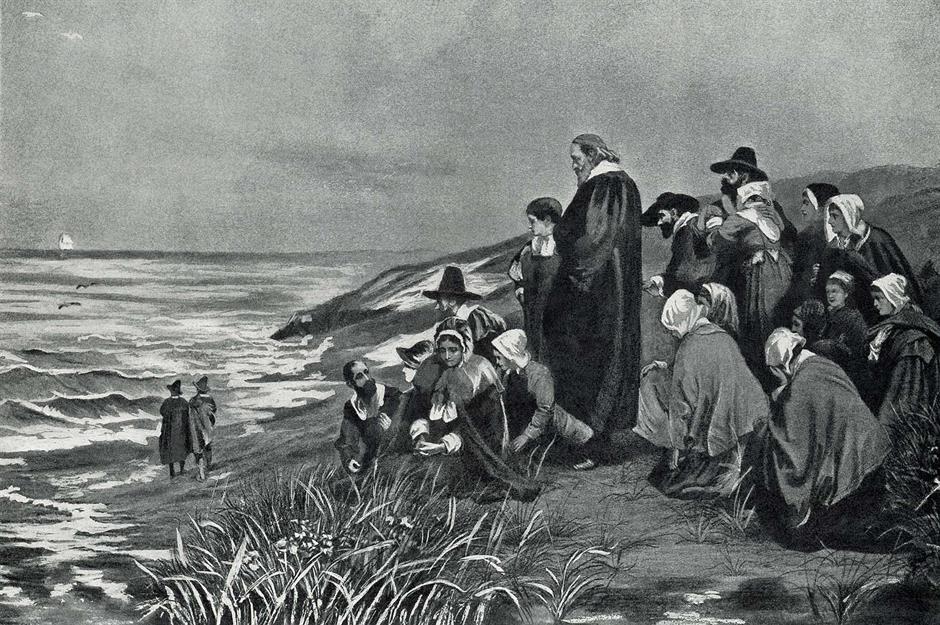

1776: Mixed beginnings

America started as both an imperial and anti-imperial project. From the settlers at Jamestown to the pilgrims of the Mayflower, the European settlements that would become America were set up by colonial men and women who owed allegiance to colonial crowns. They’re still known as colonists and their regions as colonies – of which there were eventually 13.

But American identity was forged during the American Revolution, in which the colonists rebelled against an overseas king to found a republic based on liberty. This liberty was enshrined in the Constitution, but it didn't quite mean what it means today. In the world of 18th-century nation-building, freedom was no barrier to expansion, annexation, and conquest.

Sponsored Content

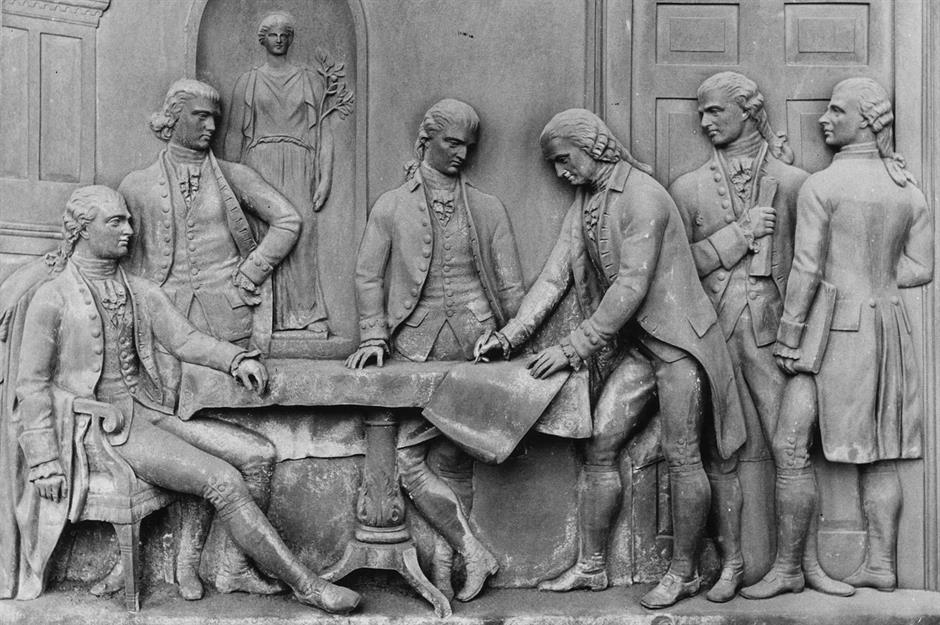

1783: A new power rises

Yale historian Paul Kennedy argues that "from the time the first settlers arrived in Virginia … this was an imperial nation, a conquering nation," and certainly the Founding Fathers weren’t as anti-empire as you might think. George Washington called America "an infant empire"; Alexander Hamilton dubbed it "the embryo of a great empire"; and Thomas Jefferson wrote in 1786 that the US was "the nest from which all America, north and south, is to be peopled."

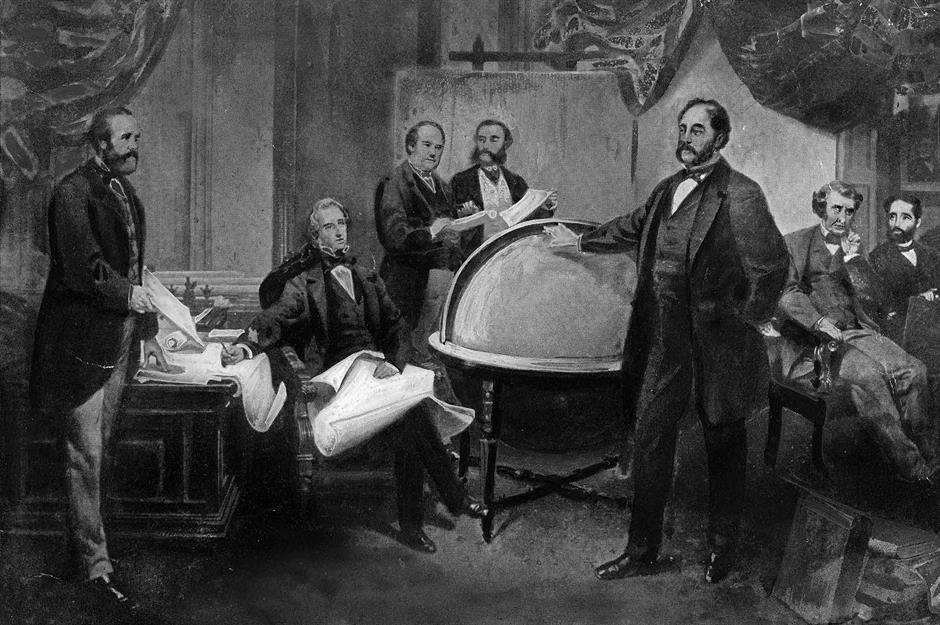

The signing of the 1783 Treaty of Paris (pictured) officially ended the war against the British, and with it what is usually termed ‘the colonial period.' But as American eyes turned westwards, another colonial period was just beginning.

1780s: Expansion begins in earnest

British rule had been a barrier to expansion (a 1763 decree banning settlement west of the Appalachian Mountains had been hugely unpopular), and from 1780 pioneers began pouring west to make their fortunes. The land's native inhabitants stood in their way, leading to a series of bloody wars often ended by unequal treaties imposed by the federal government. After losing the sprawling Northwest Indian War, a confederacy of native nations was forced to sign the Treaty of Greenville in 1795, ceding modern-day Ohio and parts of several other states.

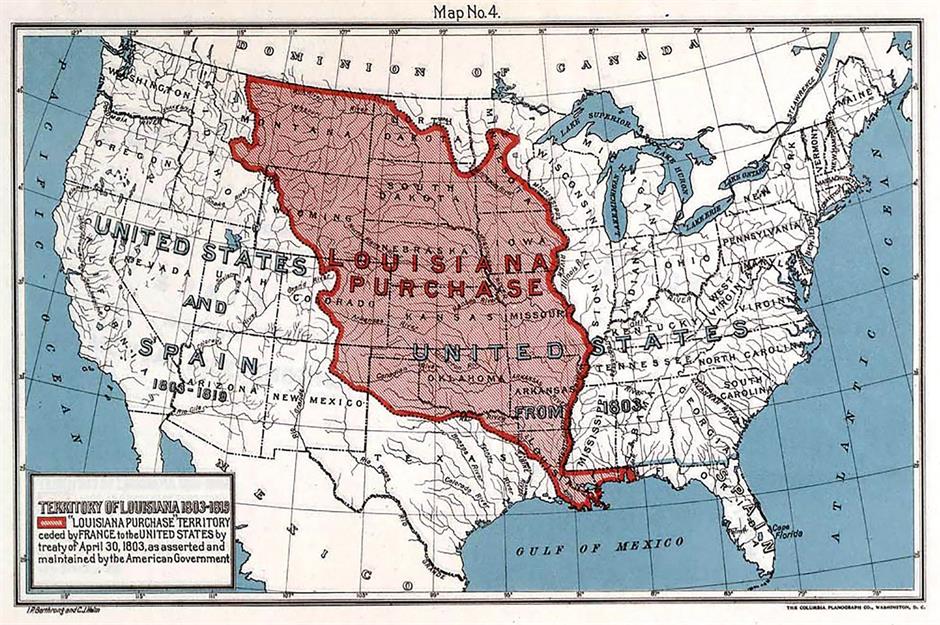

1803: The Louisiana Purchase

Invasion and annexation have long been the traditional ways to increase the size of your dominion, and while America was no stranger to either, it realized early on that buying land could be quicker and simpler than fighting for it. The top five largest land purchases in history were all conducted by the United States in the course of the 19th century – and the Louisiana Purchase was the largest of them all.

Napoleonic France needed cash for its Napoleonic Wars, and sold its entire North American territory: 828,000 square miles stretching from Louisiana in the south up beyond what is now the Canadian border. America paid $15 million for land covering 15 modern-day states.

Sponsored Content

1819: Florida

France was not the only European power that knew its North American influence was waning, and was keen to take a chunk out of the US bank account. The Spanish had been the first Europeans to make inroads into what is now the United States, setting up camp in St Augustine in 1565, but by the 1800s their grip on Florida had been tenuous for some time. In 1819, Spain agreed to give up its claim to the peninsula in exchange for American assumption of $5 million of debt.

Love this? Follow us on Facebook for history content and travel inspiration

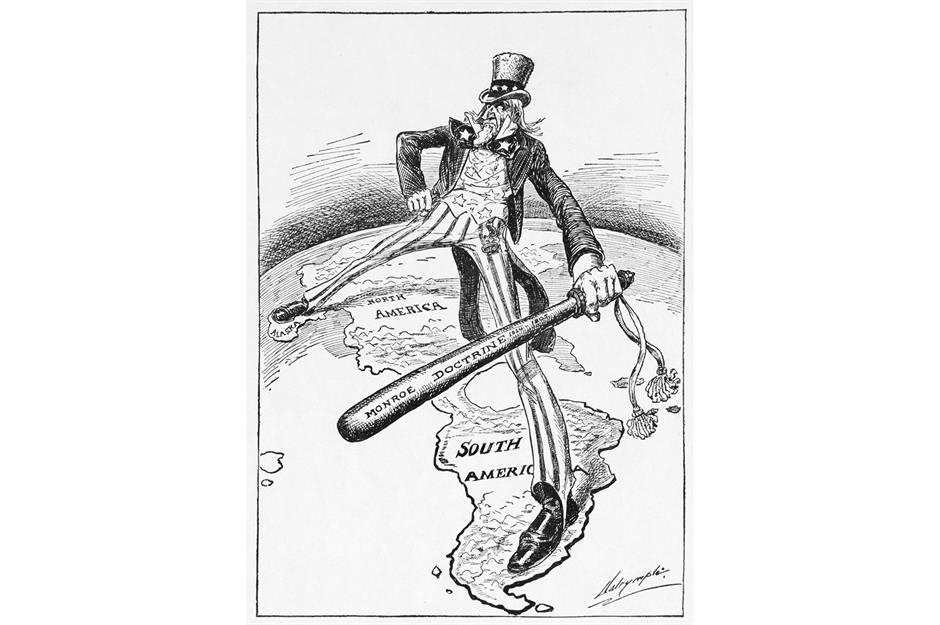

1823: The Monroe Doctrine

Fast forward four years, and America was flexing its muscles on the world stage. George Washington famously warned against "the insidious wiles of foreign influence," and in 1823 5th President James Monroe picked up the theme by warning Europe that the US would not tolerate colonial endeavors in North or South America, and that both were in America's sphere of interest.

The Monroe Doctrine became a longstanding template for American foreign policy. It was sort of anti-imperialist, as it explicitly pushed back against European empire, but it put no limitations on America and implied US influence across two continents. Eminent historian William Appleman Williams described this attitude as "imperial anti-colonialism."

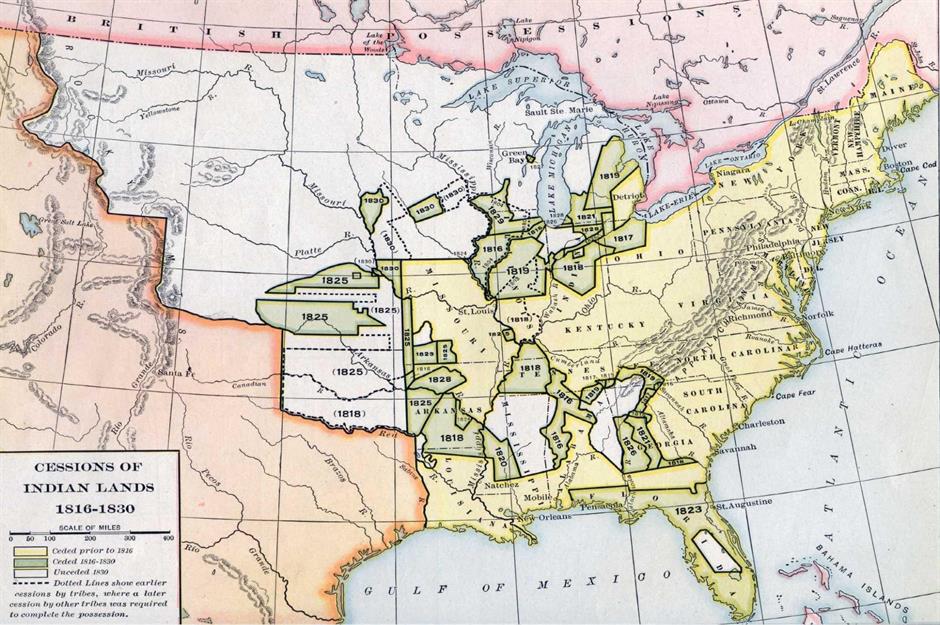

1830: The Indian Removal Act

Whether the land was bought, conquered, or simply 'settled,' Native American inhabitants were shown little mercy by the American expansionist machine. This map shows ceded Indigenous land between 1816 and 1830 – the year of the Indian Removal Act, which authorized the forced relocation of approximately 100,000 Native Americans to reservations in Oklahoma. Known as 'the Trail of Tears,' around 15,000 starved, froze, or died of exhaustion and disease on the march west, and it remains one of the most infamous episodes in US history.

Sponsored Content

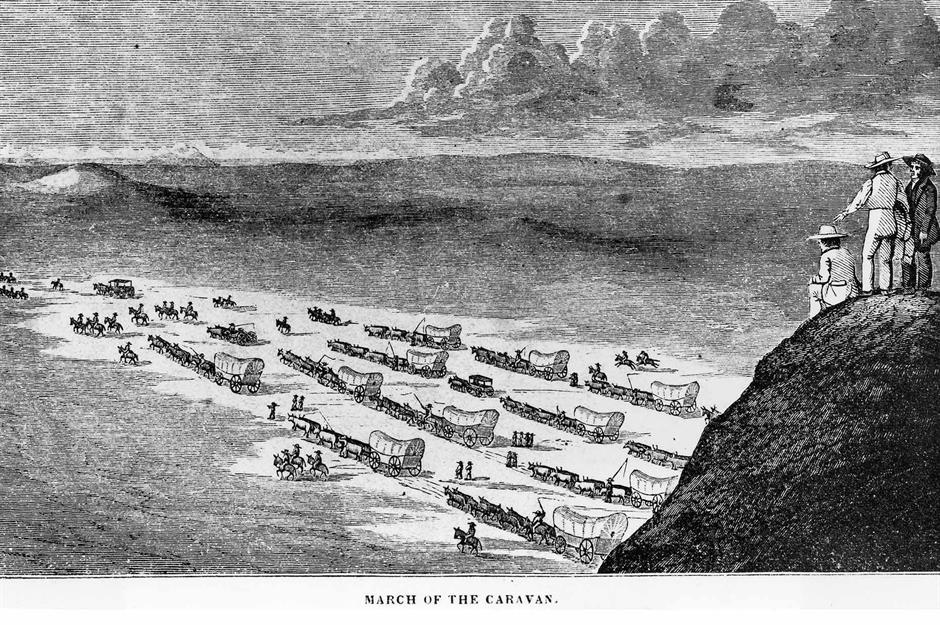

1845: 'Manifest destiny'

In 1845, newspaper editor John O'Sullivan wrote that it was "our manifest destiny to overspread the continent, allotted by Providence." The phrase became a byword for America's attitude towards the west – that the United States was divinely predestined to bring democracy and Christianity to the whole of North America. The western horizon became a symbol of romance and opportunity, and writer Horace Greeley famously urged, "go west, young man, and grow up with the country."

This mindset closely resembles colonial attitudes elsewhere in the world, and was controversial even in its time. Some Americans considered it a shallow justification for land theft, and contradictory to the principles of a republic.

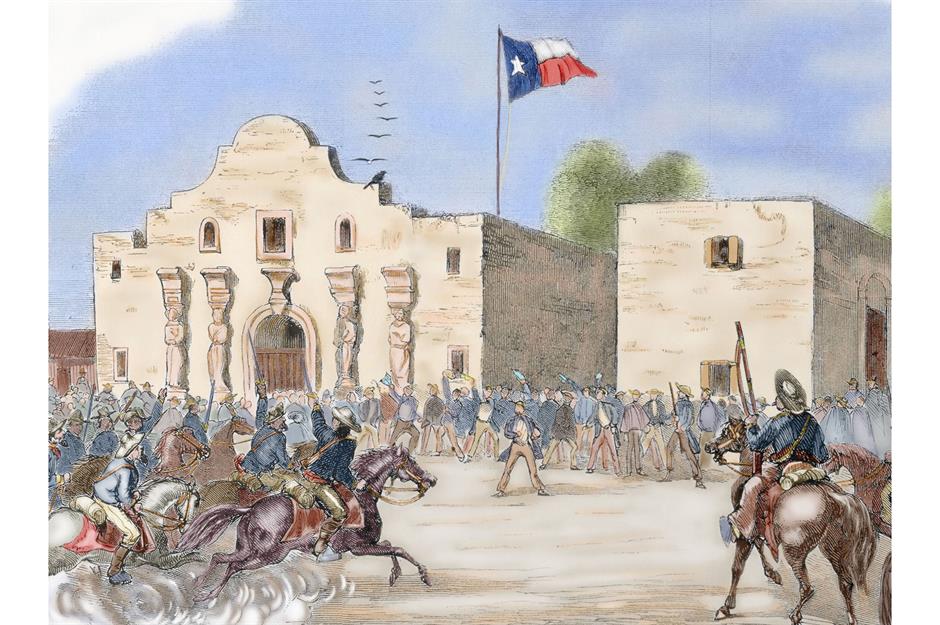

1845: Texas Annexation

President James Polk was never a candidate for Mount Rushmore, but his time in the Oval Office saw America's greatest territorial expansion to date. The 1846 Oregon Treaty secured much of the northwest, but Texas was a far greater prize. The soon-to-be state had fought a successful war of independence against Mexico in the 1830s, and was willingly annexed by the US in 1845.

The Texan question highlights another stain on America's republican credentials: slavery. Mexico abolished slavery in 1829, and Texas rebelled partly to defend it. By 1845, much of Europe had outlawed the practice, but it took the US another 20 years – and a civil war – to do so.

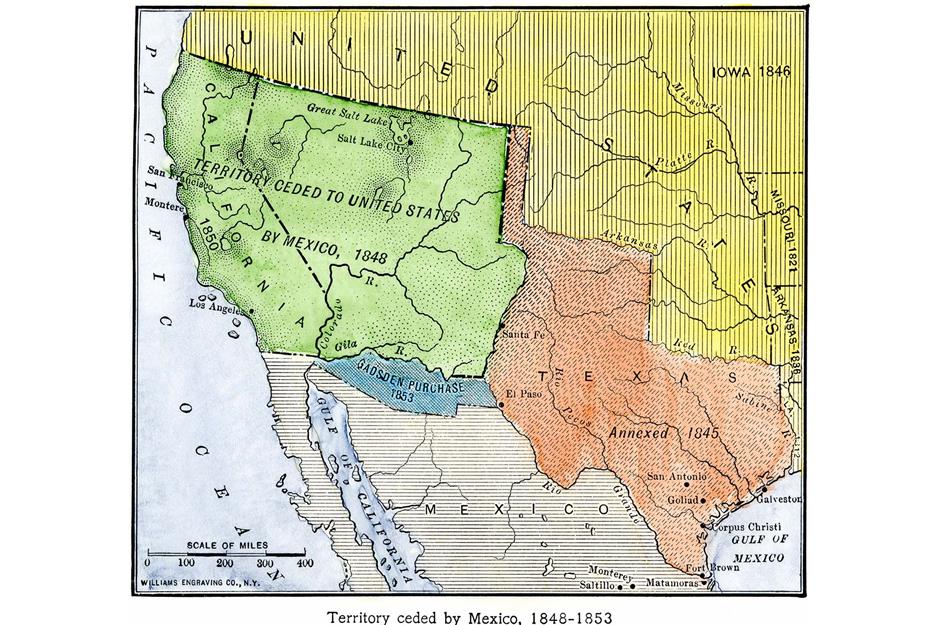

1848: Mexican Cession

Mexican-American relations simmered following the Texas Annexation, and a border dispute soon boiled over into a war that the US convincingly won. At peace talks America again reached for its wallet and paid Mexico $15 million, while the Mexicans ceded an astonishing 525,000 square miles of land – 55% of their pre-war territory, covering the states of California, Nevada, Utah, Arizona, and New Mexico.

Though never exactly benevolent, America's occupation of California – exacerbated by the 1848 gold rush – stands out for its brutality. Now widely termed 'the California genocide,' it saw up to 16,000 Native Americans killed in cold blood.

Sponsored Content

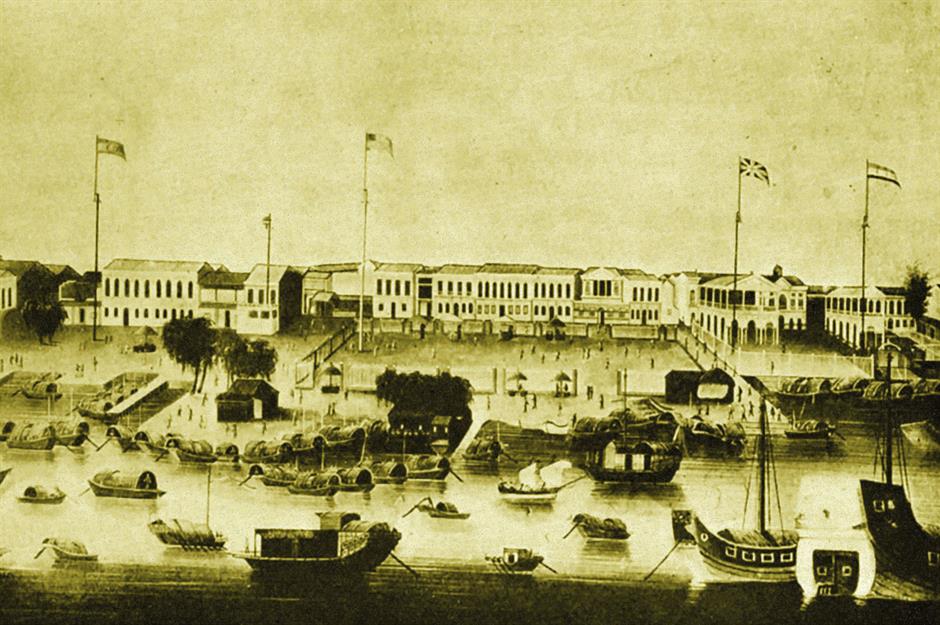

1850s: Across the seas

By the 1850s, manifest destiny had brought American dominion to the shores of the Pacific, and it soon began expanding across the ocean. Trade and commerce have long been the building blocks of empire, and America was now powerful enough to aggressively pursue commercial interests abroad. It planted outposts on islands across the Pacific, and set its gaze on the lucrative China trade.

Western powers never colonized China, but they imposed unequal treaties, secured land concessions, and staged military interventions throughout the 19th century. Treaties in the 1840s and 1850s granted America privileged access to Chinese ports and exempted Americans from local laws. Between 1848 and 1863, the US maintained its own enclave in Shanghai – the American Concession.

1853: Commodore Perry and gunboat diplomacy

The Japanese were even more resistant to foreign trade, having closed their borders to outsiders more than two centuries before. In 1853, Commodore Matthew Perry sailed four well-armed warships into Tokyo Bay, and suggested that his terrified hosts make terms – an extremely literal case of gunboat diplomacy. This proved persuasive, and Japan became the latest recipient of American commerce.

US Senator Albert Beveridge would later say in a speech: "American factories are making more than the American people can use; American soil is producing more than they can consume. Fate has written our policy for us; the trade of the world must and shall be ours."

1867: The Alaska Purchase

France, Spain, and Mexico had all yielded vast tracts of land in exchange for a quick buck, and in 1867 it was Russia's turn. Unlike earlier acquisitions, Alaska did not border US territory, and the $7.2 million deal for 586,412 square miles of barren wilderness was ridiculed by critics.

It was nicknamed 'Seward's Folly,' 'Seward's Icebox,' and 'Seward's Polar Bear Garden' after Secretary of State William H Seward, and one senator joked he'd only vote for the purchase if it stipulated "that the Secretary of State be compelled to live there." Alaska has since paid for itself many times over. Gold was discovered in the 1890s; the state was strategically crucial during World War II; and oil was found in 1968.

Sponsored Content

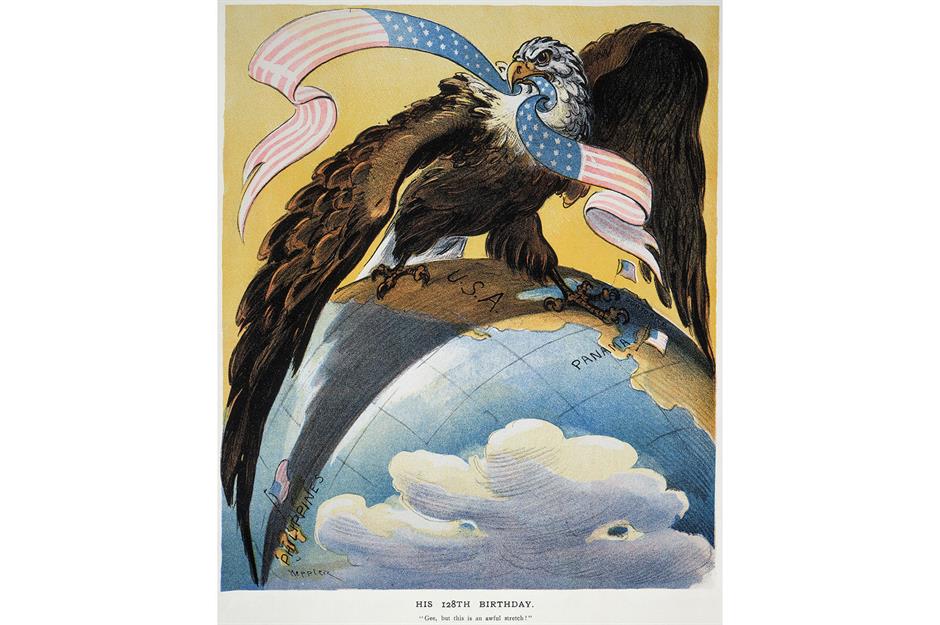

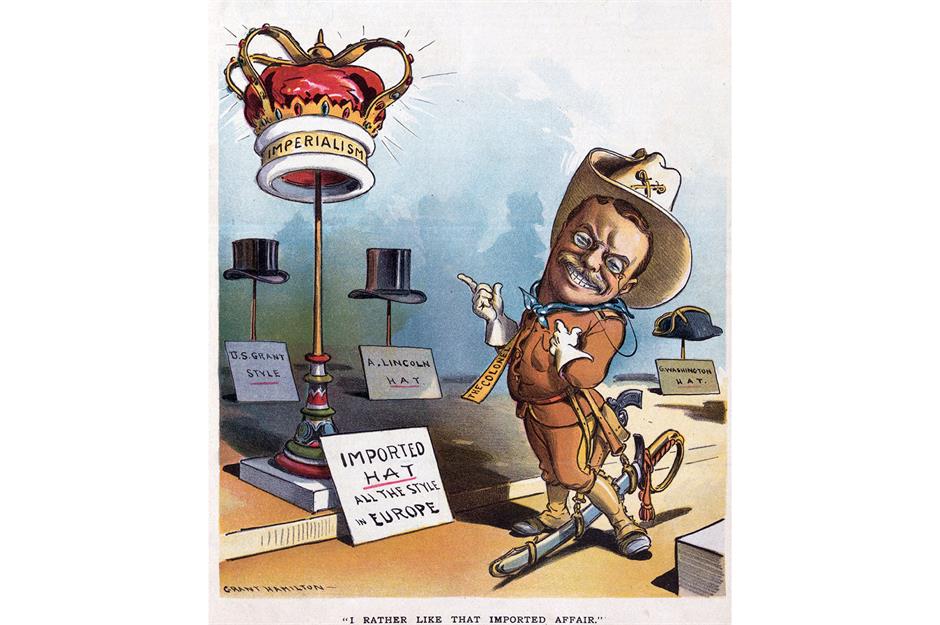

1890s: 'New Imperialism'

The late 19th and early 20th centuries are known worldwide as the age of 'New Imperialism,' as resurgent racism and rivalry between great powers saw a surge in colonial expansion. This time, America was in the vanguard, and the era would see the annexation of Hawaii, the seizure of the Philippines, a rapid accumulation of Pacific islands, various coercive actions in Latin America, and more.

Some historians paint this period as an aberration – a rare departure from America’s historic ideals. Others, pointing to longstanding policies on Native Americans, portray it as continuity and consequence.

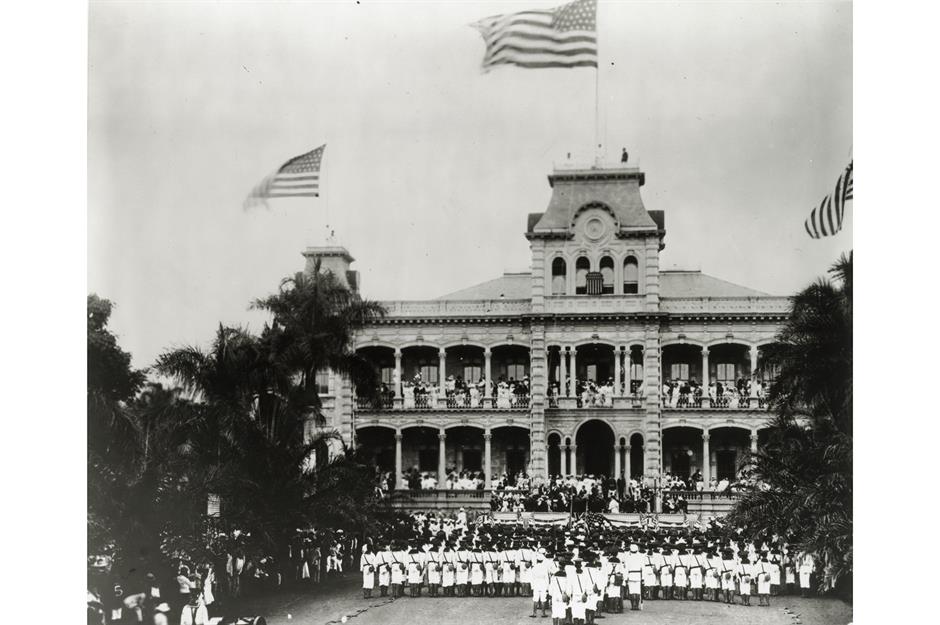

1898: Hawaii is annexed

Hawaii became the 50th US state in 1959, but barely six decades previously it had been a sovereign land with an established monarchy. Commerce was, again, the key factor: American businessmen chipped away at Hawaii's independence throughout the 19th century, and had already succeeded in outlawing the native Hawaiian language.

Hawaii's last ruler, Queen Lili'uokalani, was finally removed in a bloodless coup by American sugar magnates and US marines in 1893; pictured here are US sailors at the formal annexation ceremony outside Iolani Palace five years later. In 1993, the US government marked the centenary by issuing an official apology for "the overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaii."

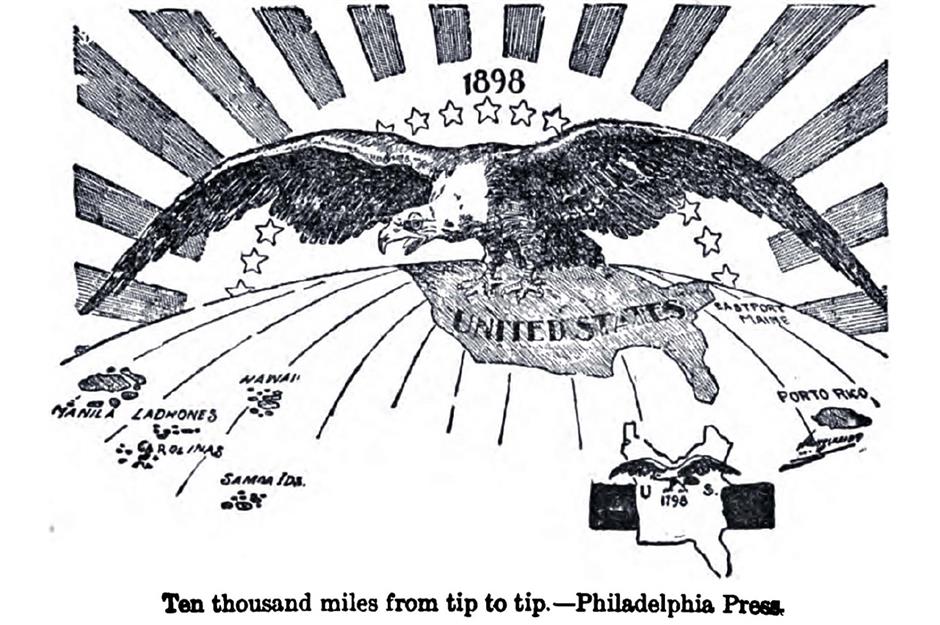

1898: Guam, Puerto Rico, Cuba, and the Philippines

1898 was a career year for US imperialism, as victory in the short-lived Spanish-American War saw Guam, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines added to America's colonial stable. America fought in support of Cuban independence from Spain, and under the surrender terms Spain ceded Guam and Puerto Rico (which remain US territories) and gave up the Philippines in return for $20 million.

Cuba's nominal independence was undercut by laws guaranteeing America's political and economic interests and granting use of Guantanamo Bay. The not-yet-president Theodore Roosevelt cut his teeth in the war, leading a notorious cavalry brigade known as the 'rough riders.'

Sponsored Content

1899: The Philippine-American War

The Philippines resisted their new colonial masters, and when the star-spangled banner was raised in Manila it heralded a bloody three-year war. A colonial mindset suffused the conflict, with US general William Shafter commenting: "It may be necessary to kill half of the Filipinos in order that the remaining half of the population be advanced to a higher plane of life than their present semi-barbarous state affords."

Hundreds of thousands died – mostly from famine and disease – but the revolutionaries were pacified. For 48 years America controlled the archipelago, first through the military and then via a series of civil administrations.

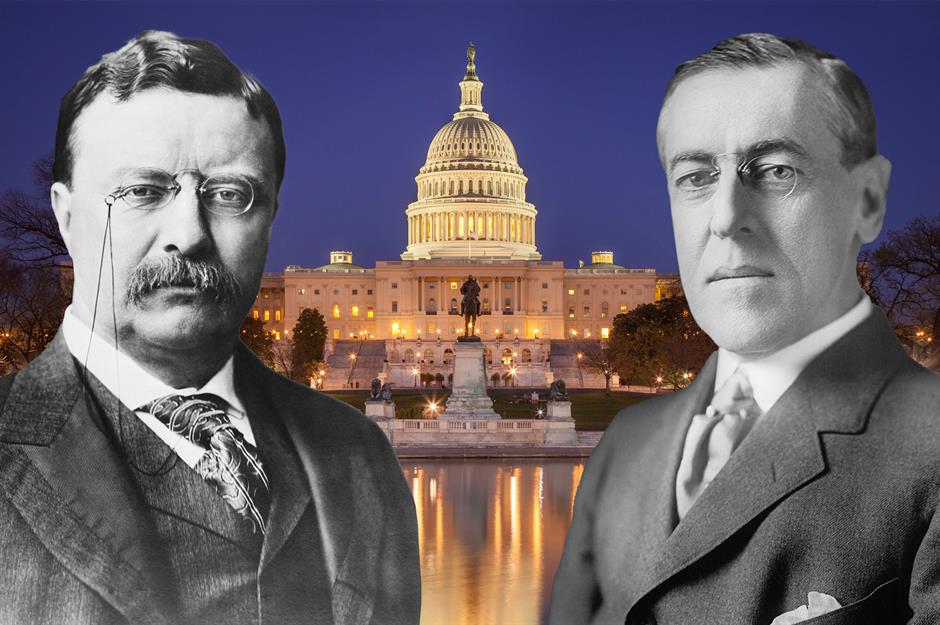

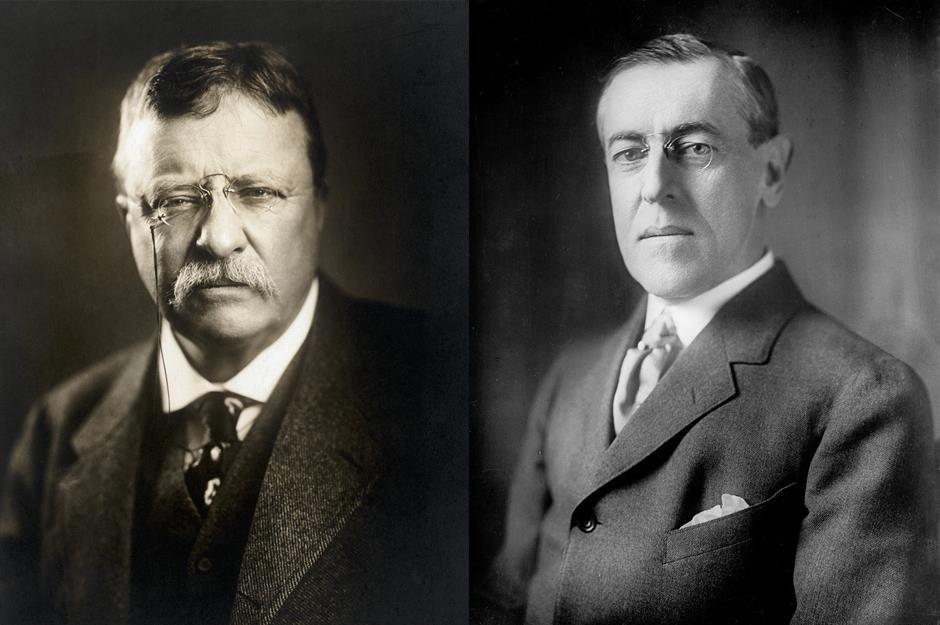

1901: Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson

Presidents Theodore Roosevelt (1901-09) and Woodrow Wilson (1913-21) are figureheads for this era of empire, and both men unabashedly used the term 'colonies.' Roosevelt began his tenure as an advocate of expansion, a believer in racial hierarchy, and a champion of military might. "I should welcome almost any war," he said, "for I think this country needs one."

In 1899, British writer Rudyard Kipling penned his famous poem The White Man’s Burden about the Philippine-American War, in which he paints American imperialism as a divinely-ordained civilizing mission – not unlike manifest destiny. Roosevelt called the work "poor poetry, but good sense from the expansion point of view."

1903: The Panama Canal

Connecting the Atlantic and Pacific oceans saved ships five months and 8,000 miles at sea. The French had attempted to build the Panama Canal in the 1880s, with huge loss of life and funds, but Roosevelt was sure America would succeed where Europe had failed. He supported Panama's independence from Colombia in 1903, and in return secured exclusive rights to build and administer the canal.

The ensuing 'Panama Canal Zone' became a de facto American colony – profits flowed into American pockets, and the zone operated under a system sometimes compared to apartheid. Only in 1979, amid deadly protests and mounting pressure, did America cede control. It was a neat case study of the different strands of American empire: territorial, political, economic.

Sponsored Content

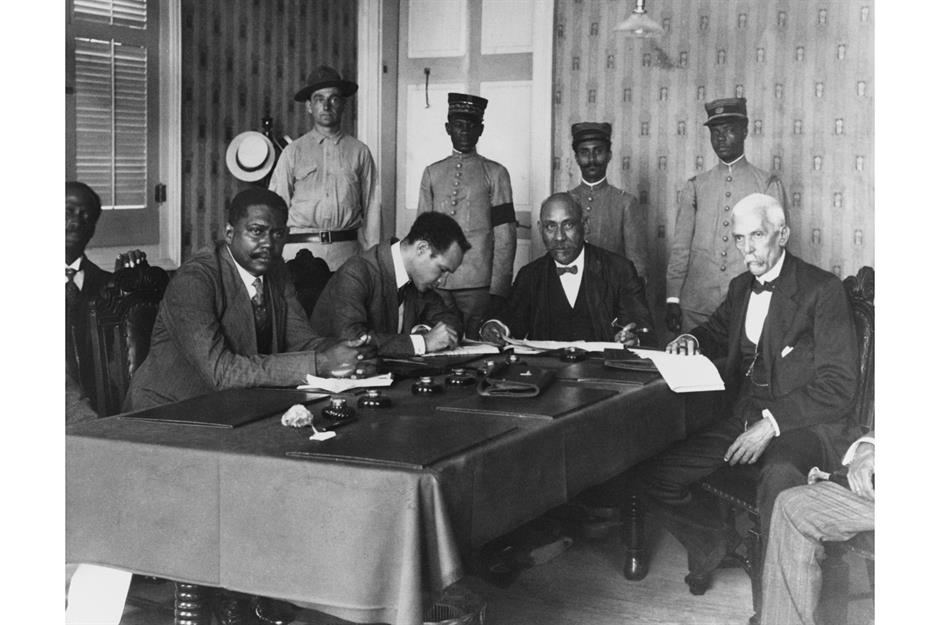

1915: The Haiti expedition

President Woodrow Wilson was an idealist, but his ideals have not aged well, and he staged more foreign military interventions than any other president. Case in point: the Haiti expedition of 1915. The country had been rocked by a string of political assassinations, so Wilson sent in the marines to restore order, protect US interests, and fend off other foreign powers.

America promptly took over the central bank, installed a pro-US president, created a US-controlled military police, and granted itself the right to intervene in Haitian affairs at any time. Racial segregation, press censorship, and forced labor followed, leading to a peasant rebellion in 1919. America only withdrew from the country under President Franklin D Roosevelt in 1934.

1940s: World War II

World War II saw America at its most anti-imperialist: fighting Nazi fascism and the ultra-nationalist Empire of Japan. Simultaneously, it saw US marines encamped across Europe, East Asia, and North Africa, and years-long occupations in Tokyo and Berlin. The shattered European powers emerged from the war with disintegrating empires and vast debts – mostly to America.

After the war, the Marshall Plan committed billions of dollars to Europe's reconstruction, and secured a favorable environment for American goods and companies, plus limitless political capital. World War II was a victory for democracy over autocracy; it also consolidated America as the most powerful nation on Earth.

Empire endures

Post-war America looked less like a traditional empire: the Philippines declared independence in 1946, Alaska and Hawaii became states in 1959, and manifest destiny faded into history. But the international reach of the CIA, interventions in Korea and Vietnam, and its status as ‘leader of the free world’ saw America's global influence hit new heights.

Today, there are American military bases in at least 70 countries around the world, while more than 100 boast branches of McDonald’s. The legacy and nature of American empire remains a highly controversial topic.

Now discover fascinating photos of America in the early 1900s

Sponsored Content

Comments

Be the first to comment

Do you want to comment on this article? You need to be signed in for this feature