Ranked: France’s most extraordinary archaeological discoveries

Fascinating finds

France is a veritable treasure trove for archaeologists, and under layers of rock and sediment lie historic sites and artefacts that tell untold stories of the nation’s past. These range from Roman ruins and dinosaur skeletons dating back millions of years to a collection of gold coins hidden in the walls of a Parisian townhouse. In our opinion, these are the most fascinating finds in the history of France. Ready to dig in?

Click through this gallery to see the most astonishing discoveries ever uncovered in France...

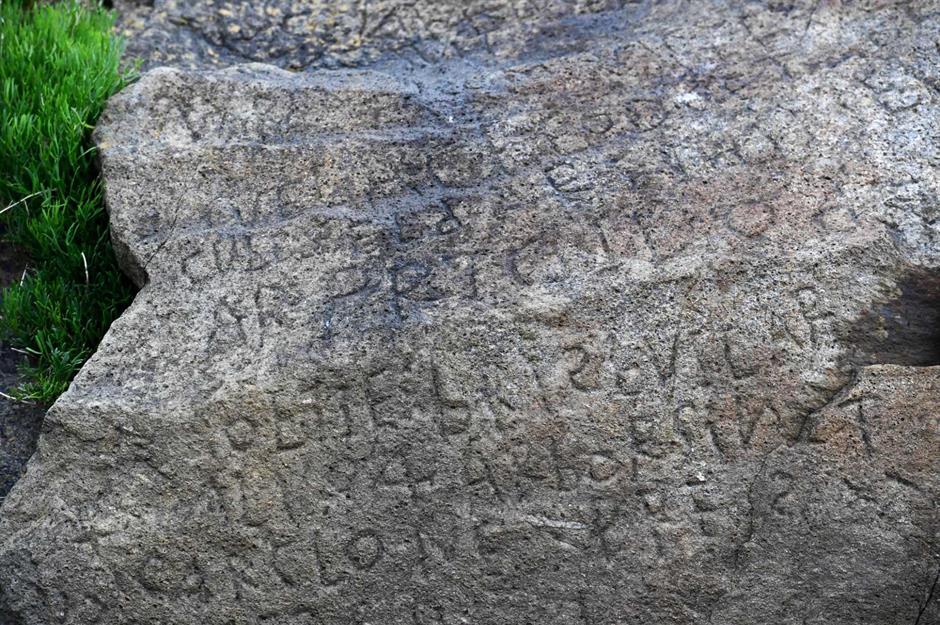

27. The Plougastel-Daoulas code

French villagers in Plougastel-Daoulas in Brittany discovered a rock – only visible at low tide – with a mysterious, unintelligible inscription. No one locally could translate the message, so they launched a competition with a prize of €2,000 (£1,671/$2,103) for anyone who could decipher the message. Two code-breakers succeeded in 2020, concluding that the rock described the death of a man named Serge who died at sea after his rowing boat capsized in the 1780s. It was written in a mixture of Breton and Welsh.

26. The Rue Mouffetard treasure

In 1938, a construction worker was demolishing a wall at 51-53 Rue Mouffetard in Paris when small rolls of canvas appeared. Inside, he found a handful of gold coins. This sparked the discovery of over 3,000 Louis XV coins in the property dating from 1726 to 1756. Documents revealed that they belonged to Louis Nivelle, who gifted them to his daughter but died before disclosing their location. Proceeds from the coins were split between the city, Nivelle’s descendents and the construction workers.

Love this? Follow us on Facebook for travel inspiration and more

Sponsored Content

25. Le Tumulus des Sables

In 2006, curious schoolchildren playing in their school playground in Saint-Laurent-Médoc accidentally dug up human bones. On closer inspection, archaeologists uncovered a burial site used from the Neolithic era to the Iron Age (roughly 5500 to 1000 BC). Radiocarbon analysis of the teeth showed that the inhabitants ate a land-based diet with little seafood, despite being close to the sea. Among the jumble of bones, they found Bell Beaker-style pottery, arrowheads and bone buttons.

24. The Marliens monument

From above, these strange mounds of earth in Marliens, around 12 miles (20km) southeast of Dijon, look like an otherworldly crop circle. Instead, they're thought to be an unusually-shaped Neolithic monument – one quite unlike anything archaeologists have found elsewhere. During the excavation, the French National Institute for Preventive Archaeological Research (INRAP) also uncovered Bronze Age wells and burial sites. The raised monument is still the oldest, most interesting feature, but its purpose and date of creation remain a mystery.

23. Château de l’Hermine

Archaeologists knew for several years that the remains of a medieval castle lay beneath an 18th-century mansion in the western city of Vannes. But they didn’t realise how extensive the remnants were until excavations began in 2023. Château de l’Hermine was originally built by the Duke of Brittany, Jean IV, in the 1380s. A ground floor emerged featuring two large towers, a ceremonial staircase, a moat and even an advanced toilet system. Fifteenth-century coins, jewellery and cooking utensils also lay among the ruins.

Sponsored Content

22. The Lava treasure

Félix Biancamaria, his brother and a friend were fishing off Corsica’s west coast in 1985 when they discovered hundreds of gold coins from the 3rd century AD. The coins feature the heads of Roman emperors including Gallienus, Claudius II (pictured), Quintillus and Aurelien. Later, Biancamaria sold the gold coins (which were technically the property of the state) and was convicted for the crime in 1994. He was arrested again in 2010 for attempting to sell another treasure from the hoard – a gold plate worth up to €8 million (£6.7m/$8.4m).

21. Filitosa

Human faces carved into granite rocks make for an unusual sight among the rolling hills and olive plantations of Corsica. But that’s exactly what Charles-Antoine Cesari discovered, lying face down on his land and covered with shrubs, in 1946. Further excavations revealed dozens of stone menhirs carved around 1200 BC, making Filitosa one of Europe’s most beautiful prehistoric art collections. Some believe the figures were created by warriors allied to Egypt’s pharaohs, as they depict intricate helmets and swords.

20. Cabrières Biota

Amateur palaeontologists Eric Monceret and Sylvie Monceret-Goujon were fossil hunting near Montpellier when they found an astounding site boasting almost 400 fossils in excellent condition. Researchers from the University of Lausanne dated the fossils to the Ordovician period, roughly 470 million years ago. They include fungi, corals and molluscs, as well as arthropods and jellyfish. It’s thought the animals were living here to avoid extreme temperatures around the equator during a period of global warming.

Sponsored Content

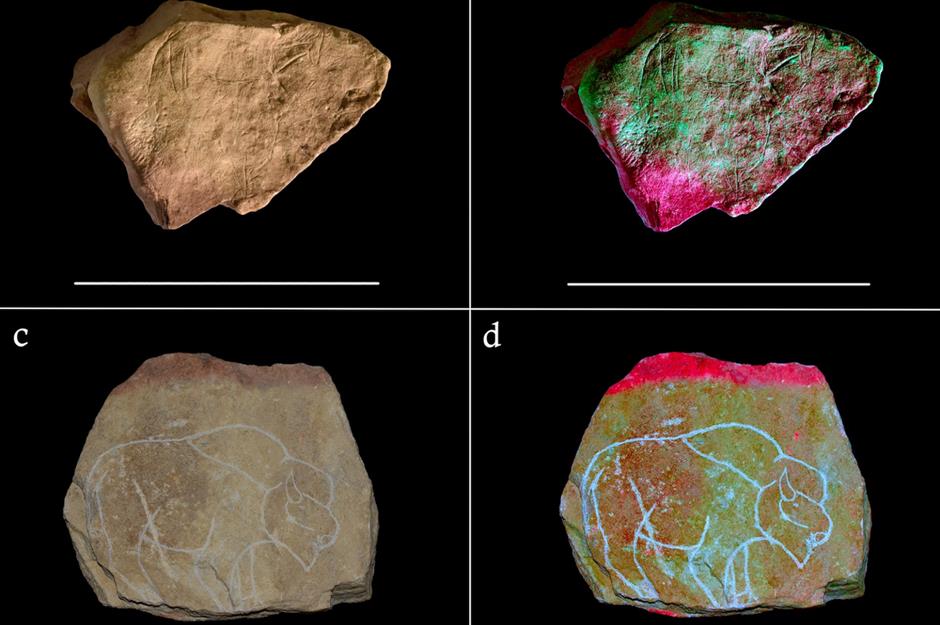

19. Magdalenian plaquettes

Could ancient tribes have created the first cartoons? These 15,000-year-old stone plaquettes were first discovered in a rockshelter near Toulouse in the 19th century, and were later acquired by the British Museum in London. They show animals – including reindeer, boar, fox and beaver – engraved in stone by the hunter-gatherer Magdalenian people, possibly for the purpose of storytelling. New research suggests that these plaquettes were deliberately placed close to open fires because the dancing light made the shapes come alive.

18. The Sainte-Colombe ruins

Bulldozers were ploughing through a patch of land in Sainte-Colombe near Lyon when they came across a 75,000-square-foot (7,000sqm) Roman neighbourhood dating from the first century AD. Nicknamed 'Little Pompeii', its inhabitants are thought to have been driven from their homes by a fire, which helped preserve the buildings and artefacts in remarkable condition. A temple, a market square, food shops and two homes are among the ruins, alongside bricks, doors, wine jugs and mosaic floors.

17. Arles-Rhône 3

Discovered in 2004, the Arles-Rhône 3 is a 102-foot-long (31m) shipwreck – a Gallo-Roman barge that sank while it was in use on the River Rhône. It was incredibly well-preserved by the muddy riverbed and its cargo of limestone blocks. Archaeologists believe it was transporting the blocks from quarries located nine miles (15km) north of Arles in the 1st century BC. After being lifted off the riverbed, it was reconstructed inside the Arles Museum of Antiquity, where you can still see it today.

Sponsored Content

16. Pyrenean mastodon

In 2014, a farmer near Toulouse unearthed a gigantic skull with two tusks on his land. He kept it hidden for two years before taking it to the Muséum de Toulouse. Experts believe it to be the bones of a Pyrenean mastodon, an extinct relative of the elephant that roamed the Earth between 11 and 13 million years ago, although the exact species is still unknown. It was an incredibly rare discovery, and the last time the remains of such a creature were discovered in the region was in 1857.

15. The Avanton Gold Cone

Mystery surrounds this golden cone hat, which was first discovered in a field near Avanton in 1844. It’s one of four similar gold hats uncovered in France, Germany and Switzerland. Archaeologists have dated the hat, which stands at 22 inches (55cm) high, to 1000-900 BC during the Late Bronze Age. Questions remain around its original significance, and experts think it could be a religious headpiece with astronomical importance, due to the sun and moon patterns inscribed on its sides.

14. Ucetia

Rumours of a lost Roman city near Nîmes circulated for years, and in 2017 archaeologists uncovered concrete proof. While excavating a school building site near the town of Uzés, they uncovered the footprint of several buildings from the 1st century BC. Urban houses with bread ovens, hypocausts (ancient central heating systems) and wine vases were present, as well as two large mosaics featuring central medallions, one of which is adorned with an owl, a duck, an eagle and a fawn.

Marvel at Europe's most extraordinary underground attractions

Sponsored Content

13. Font-de-Gaume

Just a handful of Europe’s caves with palaeolithic paintings are still open to the public, and Font-de-Gaume is one of them. Inside you’ll find more than 200 paintings of bison, horses, mammoths and reindeer dating back around 14,000 years. The artworks were discovered by teacher Denis Peyrony in 1901, when he scrambled 1,300 feet (400m) up a steep slope near his home in Les Eyzies to investigate the cave. They remain some of the earliest multicoloured cave paintings ever found in France and in Europe.

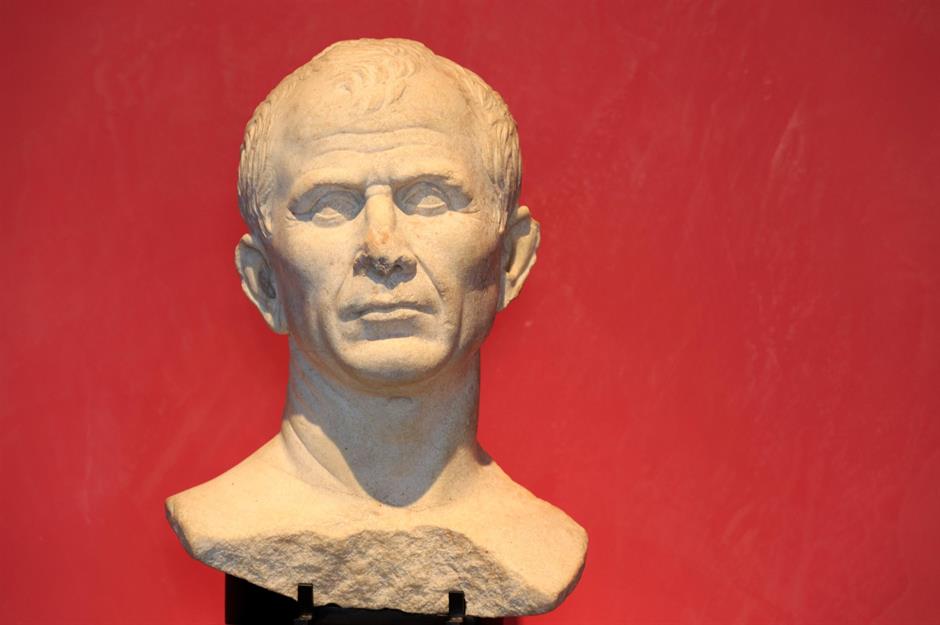

12. The Arles bust

In September 2007, underwater archaeologists diving in the River Rhône in Arles came across a life-sized marble bust on the riverbed. Once they’d hauled it to the surface, they realised it was a depiction of Julius Caesar. The Roman dictator had founded a colony in Arles in 46 BC, and the bust, with its lined face and balding head, boasts realistic features typical of Roman Republic-era portraits. It’s the oldest image of Caesar known today.

11. The Agris helmet

If you walk through the Musée d'Angoulême, you’ll spot this gleaming ornate helmet dating back to 350 BC. Made from iron, bronze and gold, it’s one of the world's most beautiful examples of Celtic metalwork. French explorers found fragments of the helmet while venturing through a cave in Agris in May 1981. Formal excavation revealed other parts and it was reassembled. With its intricate detailing, it’s thought to be a ceremonial headpiece, rather than one made for battle.

Sponsored Content

10. The Saint-Bélec slab

This 4,000-year-old engraved slab is thought to be the oldest known three-dimensional map in Europe. First discovered in 1900 by archaeologist Paul du Châtellier while digging up a prehistoric burial ground in Finistère, it was taken to a private museum before moving to the Musée des Antiquités Nationales in 1924. Unfortunately, it was then forgotten in the museum’s cellar until it was rediscovered in 2014. Using 3D surveys, researchers believe the slab bears a prehistoric map of an area around 19 by 13 miles (31 by 21km) in western France.

9. Thermes de Cluny

In the very heart of downtown Paris you’ll find one of the most extensive Roman bath complexes in northern Europe – one of only a few remaining buildings from the ancient Roman city of Lutetia. The 2,000-year-old baths were partly preserved by the Hôtel des Abbés de Cluny, a 15th-century townhouse built next to and on top of the ancient structure. Today the frigidarium is the best preserved room, with its vaulted ceiling and reliefs depicting ships.

8. The Tautavel tooth

Twenty-year-old Valentin Loescher was volunteering at a dig in the Arago Cave near Tautavel when he pulled a tooth out of the dirt. The history of art student had unwittingly discovered what could be the oldest human remains found in France, said by palaeoanthropologists to date back around 560,000 years. It’s thought that the incisor belonged to an adult who lived during a cold, dry period of history. It’s likely they would have hunted horses, reindeer, rhinoceroses and bison.

Sponsored Content

7. The Cosquer Cave

Experienced scuba diver Henri Cosquer was exploring the Calanques on the south coast when he spotted a gap in the rockface, 118 feet (36m) below sea level. He followed the 574-foot-long (175m) crevice into an underwater cave, filled with more than 480 paintings dating back 30,000 years. Handprints, penguins, deer and bison were among the illustrations depicted on the walls. Rising sea levels meant that the cave had been inaccessible for around 20,000 years. The original cave has been sealed off, but you can visit a replica on land.

6. The Swimming Reindeer

Artistry was just as important 13,000 years ago as it is today. Engineer Peccadeau de l'Isle was working for a railway company in 1867 when he came across a rockshelter in the village of Montastruc. Here, broken into two pieces, he found an impressive reindeer sculpture carved from a mammoth tusk in 11,000 BC during the last Ice Age. The artist’s skills can be seen in the exact proportions and realistic depiction of the animals. It’s one of France’s most important historical artworks, although it now resides in the British Museum in London.

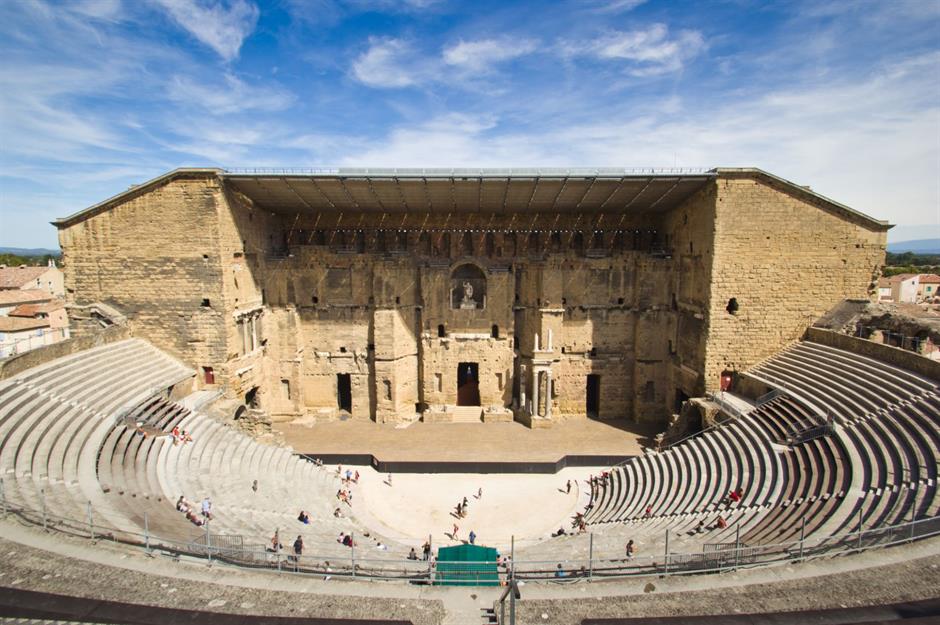

5. The Roman Theatre of Orange

Located near the southern French city of Avignon, this sprawling site is one of the best-preserved Roman theatres in the world. Built and opened in the 1st century AD, this UNESCO World Heritage Site could seat more than 9,000 people and hosted ancient performances ranging from tragic dramas to mime shows. After its closure in AD 391 it fell into disrepair, and became subsumed by houses until restoration work began in 1825. Over the next 100 years, excavations revealed 76 original columns and evidence of a wooden acoustic roof.

Sponsored Content

4. Titanosaur skeleton

Archaeology enthusiast Damien Boschetto was walking his dog in a forest in Montouliers when he came across a bone poking out of the ground. It turned out to be the skeleton of a 33-foot-long (10m) titanosaur that lived between 70 and 72 million years ago. Remarkably, it was 70% intact – a rare occurrence – with bone connections visible from the back of the skull to the tail. It’s currently being studied at the Musée de Cruzy, where it will hopefully eventually go on display.

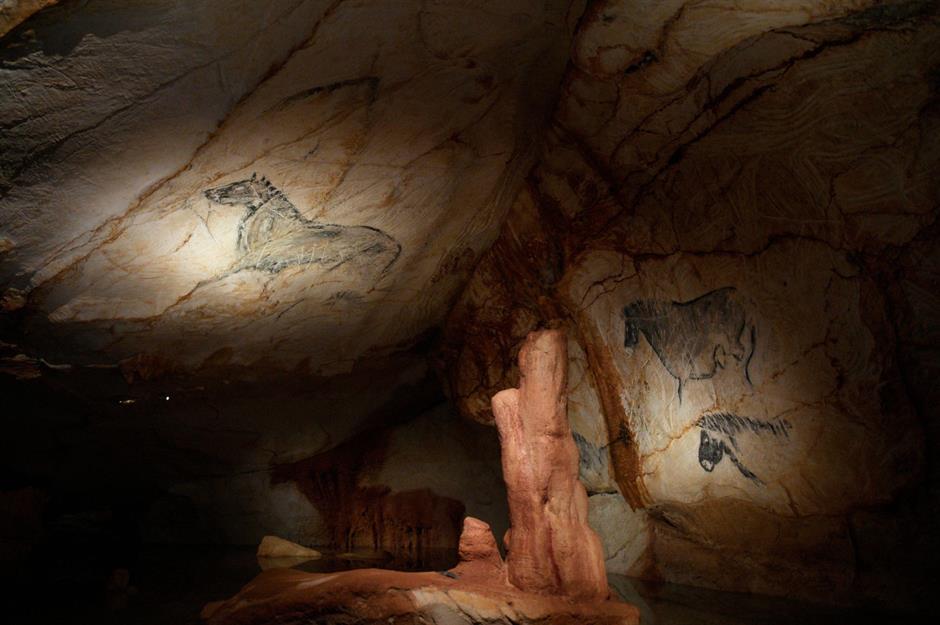

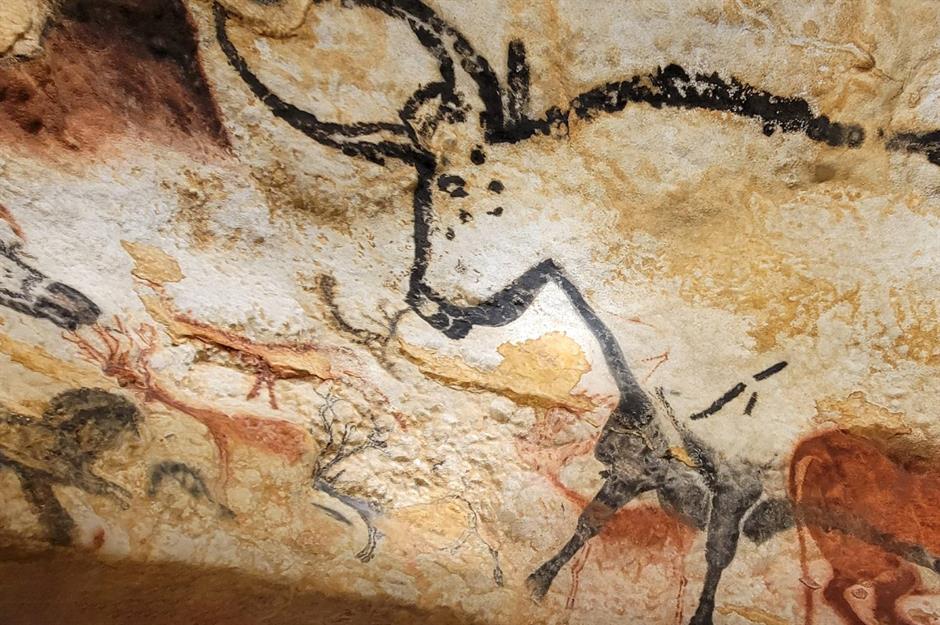

3. Lascaux Cave

In 1940, four teenage boys accidentally stumbled across the Lascaux cave network near Montignac in the Dordogne. They told their teacher, Léon Laval, who alerted archaeologist Henri Breuil to their discovery. Inside, he found vivid wall paintings of cows, bison, horses and humans that were estimated to be 20,000 years old. The caves were closed to the public in 1963 to preserve the paintings, but they are widely thought to rank among the best prehistoric artworks ever discovered.

2. Glanum

For more than 1,500 years the ancient town of Glanum was buried beneath the olive trees and fields of Saint-Rémy-de-Provence. Only the triumphal arch and mausoleum at the town's entrance were visible above ground. In 1921 excavations began under Jules Formigé and Pierre de Brun, sparking decades of digging that revealed an astonishingly extensive set of Roman remains. Today, you can see evidence of a grand Roman forum, temples, shops, public baths and rich residential villas.

Sponsored Content

1. The standing stones of Carnac

No one knows why the 3,000 standing stones at Carnac are positioned in symmetrical, evenly-spaced rows. Some believe them to be a burial site, while others think they were religious monuments. Today, they're thought to be the world’s largest group of man-made standing stones. Erected around 6,000 years ago, the menhirs were first excavated and surveyed by the Scotsman James Miln in the 1870s. Archaeologists think they're even older than the formations at Stonehenge, to which Carnac is often compared.

Now discover our ranking of France's prettiest small towns and villages

Comments

Be the first to comment

Do you want to comment on this article? You need to be signed in for this feature