The woman who spent five years cycling around the world

A life-changing journey

Back in 2015, Hannah Darvill was restless. She had ended a long-term relationship a few years earlier and was becoming increasingly frustrated by her uninspiring job in consulting. So, she decided to quit. Turning her back on her hectic London lifestyle, Hannah embarked on a nomadic existence and spent the next five years exploring the world by bike. It was an experience that would prove transformative.

Click through the gallery to discover her fascinating story…

The inspiration

“In my mid-thirties, I gradually pulled various rugs out from under myself in pursuit of a deeper relationship with myself and others. I’ve always loved travelling and having cycled solo from London, England to Lesbos in Greece a few summers before, I was not new to solo bicycle travel. But the decision I made in 2015 to quit working and become nomadic was different as it was less about going anywhere in particular and more about having a lot more time just to be. I told friends I hoped to fall in love with new places, paces and faces,” says Hannah.

The journey begins

How to finance such a lengthy trip was obviously going to be a major concern, but a friend helped Hannah calculate that renting out her house for a few years could cover both her mortgage and travel expenses, so long as she kept them to a minimum. She set out from her home in Hackney, London in September 2015 and arrived in France not long after. An early challenge was getting to grips with wild camping, a key aspect of travelling long term within her means. “I knew I had to nail it, so I started trying more or less straight away but I was so scared," recalls Hannah.

Sponsored Content

Feeling the fear of camping and doing it anyway

“By November all the campsites around the Mediterranean had closed so I had no choice but to feel the fear and do it anyway,” she says. Experience taught her that “the correct way to do it is to camp somewhere you cannot possibly be seen. The wrong way to do it is to camp somewhere you could conceivably be seen, then lie awake all night wondering if that sound of a beetle under the tent or your stomach rumbling is actually an axe murderer creeping up on you. After three to four months, I’d got the hang of it.”

Travelling light

The other big challenge was having to carry as little as possible. “Having done a fair bit of cycle travel before, I already had a pretty clear idea about the basics you have to have, especially if you’re travelling solo. You can only get it down so much. You’ve got to have camping gear, you’ve got to eat and have water, you’ve got to have clothes for different weather conditions. I had very little technology, just a Kindle and phone with no SIM card in it for offline maps and keeping in touch with people via WiFi.”

Love this? Check out our Facebook page for more travel inspiration

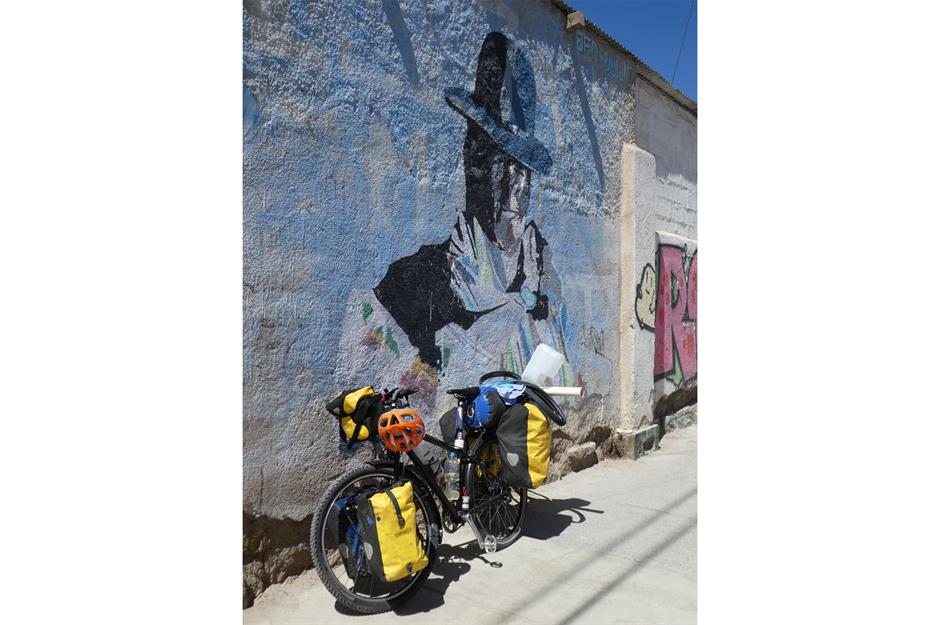

Although not that light

“It’s very liberating to travel light. That said, my Thorn touring bike weighs about 18kg and I usually had 20-25kg of stuff in my six panniers giving a total of about 40kg, or approximately 2/3 of my touring body weight. One thing I always had that a lot of cycle tourists don’t have is one proper outfit for wearing off the bike, a pair of jeans and a shirt and a couple of t-shirts, because I spent quite long periods in cities and I did not want to be walking around in Lycra shorts and a stinky yellow t-shirt."

Sponsored Content

The first 18 months

For the first 18 months of her travels Hannah toured around Europe, cycling in various loops as far as Lisbon and Istanbul via Lesbos, where she volunteered at an unofficial refugee camp for a while. She travelled down to Portugal, east as far as Turkey, north as far as Sweden and then back down to the Iberian Peninsula again.

Route planning

When it came to day-to-day route planning, she rarely had a specific destination in mind. “It kind of depended on the country I was in. In Europe there are so many roads going everywhere that it often didn’t matter that much,” she says. “At other times I’d plan to meet friends or my brother in a specific place and they’d fly out, sometimes with a bike, sometimes not, and meet me for a route section or a city or a country and that would give me a reason to be in a place by a certain date.”

A birthday and Brexit

One of the main reasons Hannah stayed in Europe for all of 2016 was that she wanted to celebrate her 40th birthday in the UK with friends. The Brexit Referendum was, of course, dominating the news agenda that year and she arrived back in the UK the day the result was announced having had a friend vote for her. “Because of that result it would now be impossible for a British citizen to cycle around Europe for the length of time I did back then,” she notes sadly.

Sponsored Content

The next stage

The next stage of her trip was inspired by a talk she heard at the Cycle Touring Festival about the relative ease for a European or British passport holder to cycle from Colombia to Patagonia as you don’t need any visas. Having organised a conference in Vancouver, Canada in 2017, Hannah figured it made sense to start there and then pass through the US, Mexico and Central America on her way to Colombia.

The challenging road culture of the US

It’s fair to say that cycling through the US during 2017 was not Hannah’s favourite experience, largely down to the attitude of other road users. “I don’t think the road culture there is very cyclist friendly. There’s a sense that you should get off the road, because roads are for cars. I can think of at least one occasion when someone drove in such a way that I’m in absolutely no doubt that their intention was to terrify me,” she says.

A suspicion of independent travellers

She also sensed a general suspicion of independent travellers. “There’s a huge homelessness problem in the US and I found that if you’re travelling with a tent, you’re generally assumed to be homeless and not welcome. I was hassled by the police a number of times and on one occasion they even tried to get me to move on in the middle of the night. Eventually I managed to persuade them I couldn’t travel in the dark and they let me stay until dawn.”

Sponsored Content

Cyclist friendly Central and South America

Although many people Hannah met on her way through the US warned her that Central and South America, which she spent all of 2018 and 2019 cycling through, were going to be dangerous, she found the complete opposite to be true. “All of Latin America was very welcoming and travelling there is a smooth experience. Anyone who imagines the region as chaotic or hostile is gravely mistaken,” she says.

A warm welcome

“Central America in particular has a culture of welcoming bicycle travellers at fire stations and churches and other places. These places are often staffed by volunteers, and they were always more than happy to have someone different there for a night. Sometimes you’d camp inside if it was raining, sometimes out.” She recalls one fire station in Guatemala where the staff sweetly put out cones around the tents of the travellers camping there in order to protect them in case anyone drove by.

Camping in intriguing locations

“El Salvador and Honduras were slightly tense due to the elections being held there in 2017 and 2018, so people often encouraged us to camp near to their home where they felt they could keep an eye on us,” Hannah recalls. “This image was taken on a football pitch near someone’s house." Despite the nervousness in the air, Hannah remembers that when they were out cycling "people wound down their car windows to say, ‘Welcome to El Salvador'."

Sponsored Content

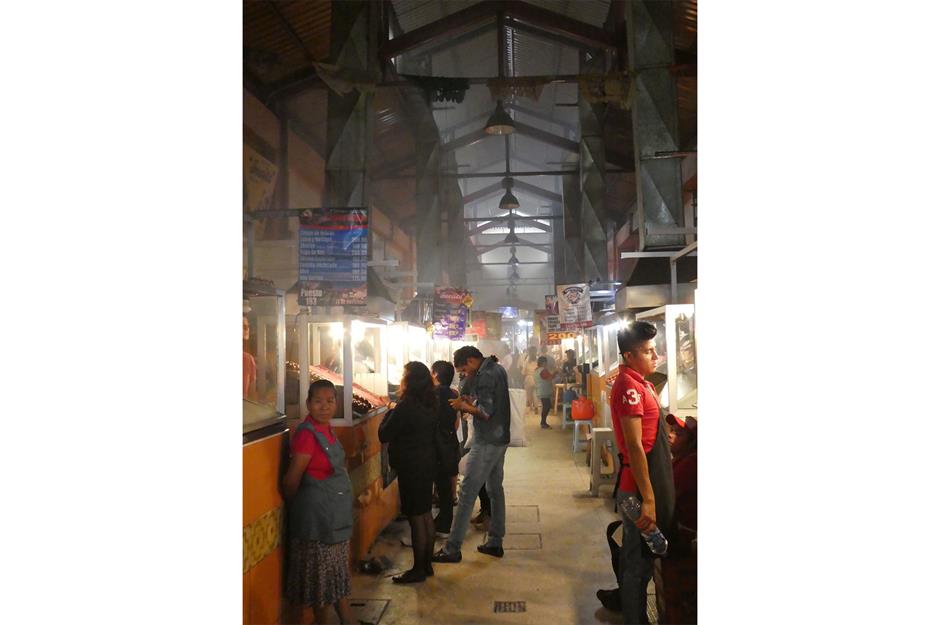

Seeing how people really live

Hannah found that cycling was a way to discover the places that ordinary travellers would miss. “Conventional travel, even backpacking, tends to take you from ‘place of interest’ to ‘place of interest’. Cycle touring means you spend most of your time at the places in between. That, combined with the pace, means you see more of how people actually live. It can also be a leveller, as most people will assume that someone who is cycling and quietly looking for spots to camp for free is probably not rich.”

Invaluable insights

“Like it or not, tourism changes a place. When you spend time in random small towns where tourists don’t go you see how ordinary people live, while having minimal impact on their way of life. In warm climates so much of daily life takes place outside; you really see a lot from the saddle of a bicycle,” says Hannah.

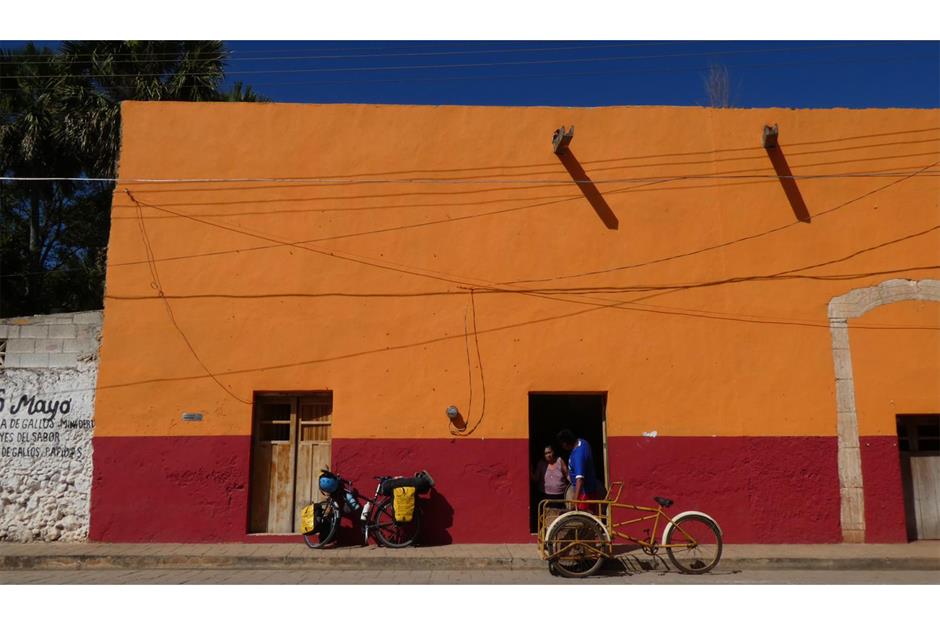

Favourite countries

Mexico and Colombia were particular favourites from this leg of Hannah’s journey. “They’re so vast and varied. I was in each of those countries for six months and I felt that I’d barely scratched the surface," she tells us. "I didn’t cycle all the way through Mexico because my priority was to get quickly to Oaxaca in the south and learn Spanish. I spent several months there and absolutely loved it, before continuing through Yucatán to Belize. I hope to return to Mexico and see some of the parts I didn’t see.”

Sponsored Content

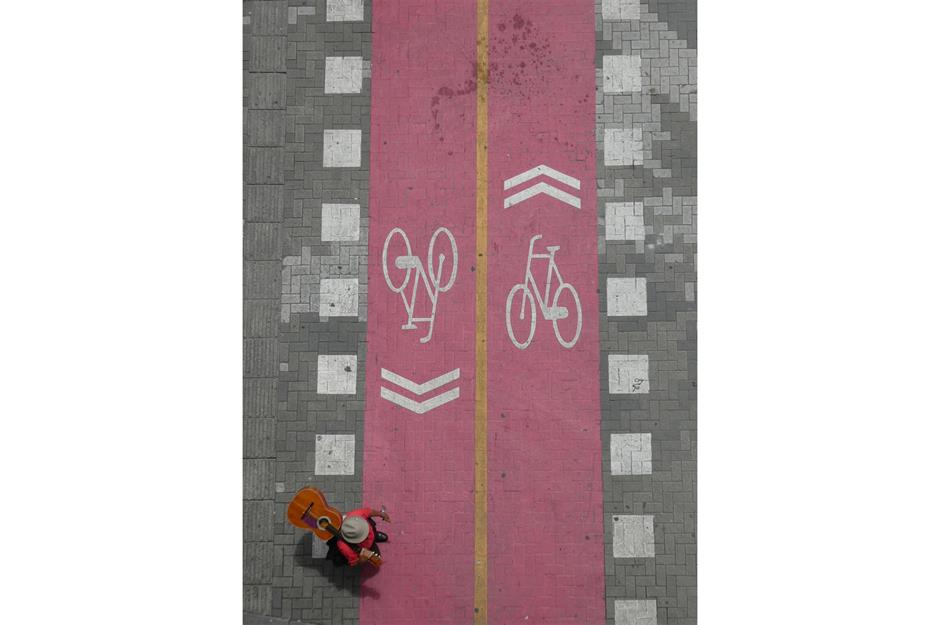

A people looking to the future

“My friend Claire did ride all the way through Mexico and her experience mirrored mine: people couldn’t have been more supportive or helpful. And the tiny minority involved in organised crime couldn’t be less interested in a passing cyclist," says Hannah. In Colombia, she found “there was an incredible sense of them feeling they've got the worst of their violent troubles behind them and want to look to the future now. That was amazing to witness.” Her experience of cycling in the country was also very positive. “Colombians hold their professional cyclists in high esteem, and this is reflected in the courteous way they share the road.”

Staying high in Peru

She reached Peru in April 2019, a country she found challenging for its sheer scale. Avoiding the cities and freeways of the coast means staying on roads high up in the Andes, in Hannah’s case often between 9,840 feet (2,999m) and 16,400 feet (4,999m) above sea level. There are few roads running from north to south so Hannah followed a remote, off-road route first mapped by bikepacking bloggers ‘The Pikes’ and known as the Peru Divide.

A helping hand

But although the terrain was challenging, she found the people to be extremely helpful to cyclists. On one occasion she took a small boat across a river in order to avoid a long journey by road and was struck by the fact that the boatmen “thought absolutely nothing of loading my heavy bike onto their tiny boat via a rickety plank.” Sometimes she would even hitch a lift up interminable ascents with friendly mining engineers.

Sponsored Content

Thoughts of ending the journey

After more than three years on the road, it was in Peru that Hannah began to think about bringing her journey to an end. “I realised that after reaching Patagonia I’d like to return to Europe and settle somewhere I could access a community and be closer to my friends,” she says.

Experiencing the world’s largest salt flat

Hannah travelled through Bolivia on the way to Argentina, a route that took her over the Salar de Uyuni, the world’s largest salt flat. Although beautiful it made for somewhat bumpy cycling conditions. “They advise against camping overnight on the salt due to the supposed risk of being hit by a drunk driver, but I couldn’t resist. In the morning, I had lots of fun trying to take funny pictures of objects on the salt while completely naked; if anyone had driven towards me, I’d have had plenty of time to put clothes on.”

Challenging roads

The roads in Argentina and Patagonia made cycling challenging and sometimes even dangerous. “In the north of Argentina, while on one of the very few paved roads, I was almost hit by a coach whose driver overtook me as another coach was oncoming,” says Hannah. Patagonia’s Carretera Austral highway, she tells us, is “a sought-after road trip but it’s largely unpaved and instead made of gravel and fine dust. Elsewhere the roads are completely flat, horrendously windy and dull. Whatever the terrain, unpaved roads are incredibly hard work on a heavy bike, especially in rain or wind.” But as it turns out, the roads were soon going to be the least of Hannah’s worries.

Sponsored Content

The pandemic hits

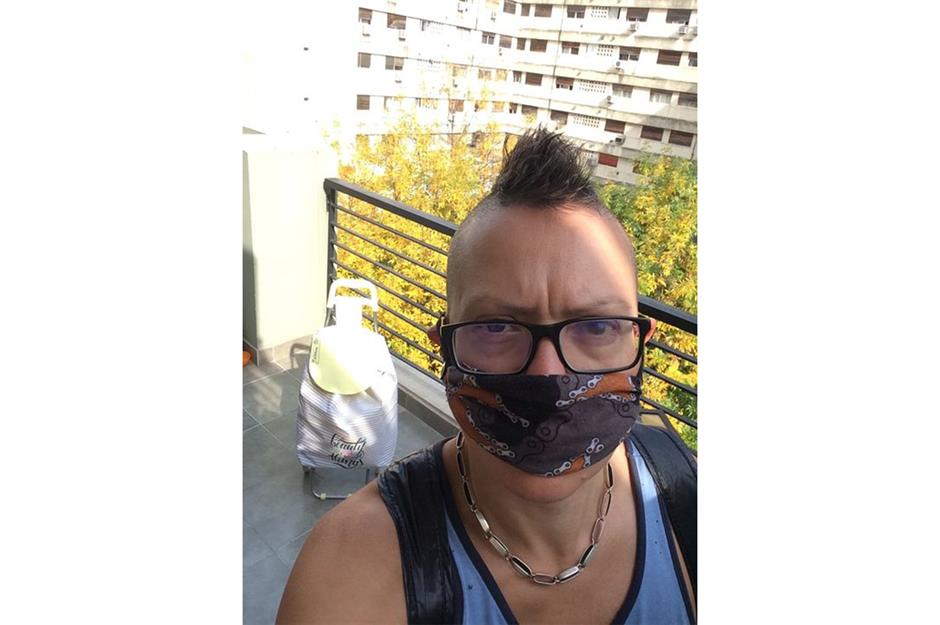

It was while she was in Patagonia that the COVID-19 pandemic hit. When it became clear that both Chile and Argentina were going to close their borders, Hannah was worried that she would be stuck on the Chilean side and have no chance of getting back to Buenos Aires for her intended flight back to Europe. “Mercifully, a border guard showed common sense and let me back into Argentina. Then I rode east and reached the nearest city, Rio Gallegos, just as Argentina was going into what turned out to be the world’s longest and strictest lockdown.”

Incarcerated

“Along with several other independent travellers I was effectively incarcerated in a municipal gymnasium for about two weeks, with a police car parked outside 24/7 to make sure we didn’t try to escape.” They were brought rice or pasta meals twice a day and allowed to speak to their respective embassies and, in the end, Hannah was allowed to board a special domestic flight to Buenos Aires on the condition she left the country, “which in practice I couldn’t do as all flights in and out were cancelled. Instead, I spent several weeks in a one-room apartment in Buenos Aires until the British Embassy organised the repatriation of citizens in May 2020.”

Freedom and the final leg of the journey

Having found Spain to be a particularly enjoyable country, and very cyclist friendly, Hannah had hoped to fly straight there and apply for residency before the Brexit deadline at the end of 2020. However, COVID restrictions made that impossible so she initially had to return to the UK. Instead, on 1 July she and her bike flew from London to Porto in Portugal. “I ended up cycling up to Santiago de Compostela, via the deserted Portuguese ‘Camino,’ to seek residency in Galicia and begin the next chapter of my life,” she says.

Sponsored Content

A new home, a new life

Eighteen months later, she bought an old watermill, O Muíño da Balsiña, in Galicia (northwest Spain). She now lives here with her cat, Xoana, welcoming friends, cyclists and paying guests. She still occasionally heads out on her bike, or in her van, with no idea where she will end up that night.

A life changing experience

Reflecting on how her journey changed her, Hannah says “having been a very social 30-something Londoner, my nomadic years turned me into a 40-something person who now actively prefers their own company. Interestingly, nearly all my friendships deepened while I was travelling, I think from having to be more intentional about how we kept in touch and the fact most of them came to meet me at least once to cycle or just hang out. That meant a lot to me. I also shared many vulnerabilities during those years of change and adventure, which I think served as an invitation to friends to do the same.”

Hannah’s tips

Hannah has three key tips for cyclists contemplating a similar adventure, the first being to “learn leave-no-trace wild camping as soon as you can. It’s what made long-term travel financially possible for me. Some people opt to impose on local people for a place to sleep but my preference is to find a hidden spot where I’m not bothering anyone, and no one will bother me. Also, learn to spot and use available infrastructure such as abandoned buildings, shelters, tables and water sources.”

Sponsored Content

Think about how you want to travel

The second tip is to “consider a mix of solo and pair travel. You’ll learn different things about yourself from the two experiences. If you decide to join forces with another traveller, communicate beforehand about your rhythms and priorities, because compromise is not always a good thing.”

Don't be a purist

Lastly, “unless you’re really pushed for time or trying to set a world record, don’t always take the fastest route. Take the quietest or most scenic one. Be open to riding a long way some days and almost no distance on others. Take a train or a bus or get a lift when the going isn’t enjoyable. Don’t over-plan; see where the road takes you.”

Comments

Be the first to comment

Do you want to comment on this article? You need to be signed in for this feature