The fascinating story of the Empire State Building

Empire State of Mind

Though the Big Apple continues to evolve around it, the Empire State Building has remained a constant of the New York skyline for more than 90 years. Rising from the streets of Midtown Manhattan, this National Historic Landmark has come to define the city that never sleeps, even more so than bagels and Broadway. Join us as we walk back through the life of this steel colossus – once the world's tallest building, now its most photographed.

Click through the gallery to learn the incredible story of the Empire State Building, America’s record-breaking skyscraper…

Reaching for the sky

Let’s turn back the clock to 1889, when the Eiffel Tower was completed in Paris and proclaimed the world’s tallest man-made structure at 984 feet (300m). This sparked a new fascination with skyscrapers, spurring American architects to start making plans for a building that could surpass the Iron Lady. By the turn of the 20th century, the race to the clouds was on in New York City – the Metropolitan Life Tower (700ft/213m) sprung up in 1909, followed by the Woolworth Building (792ft/241m, pictured here under construction) in 1913. But neither could steal the Eiffel Tower’s title.

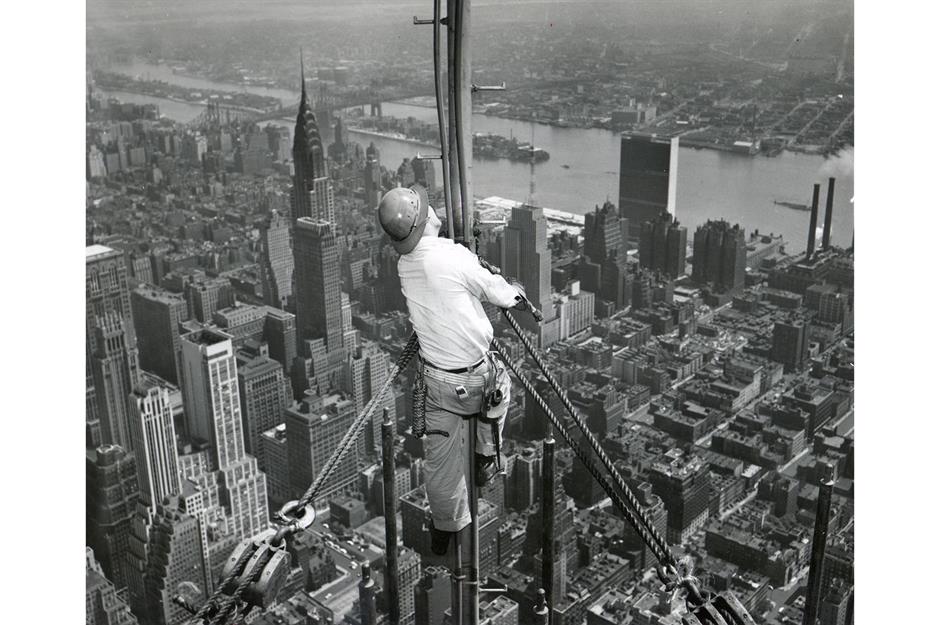

Hot property

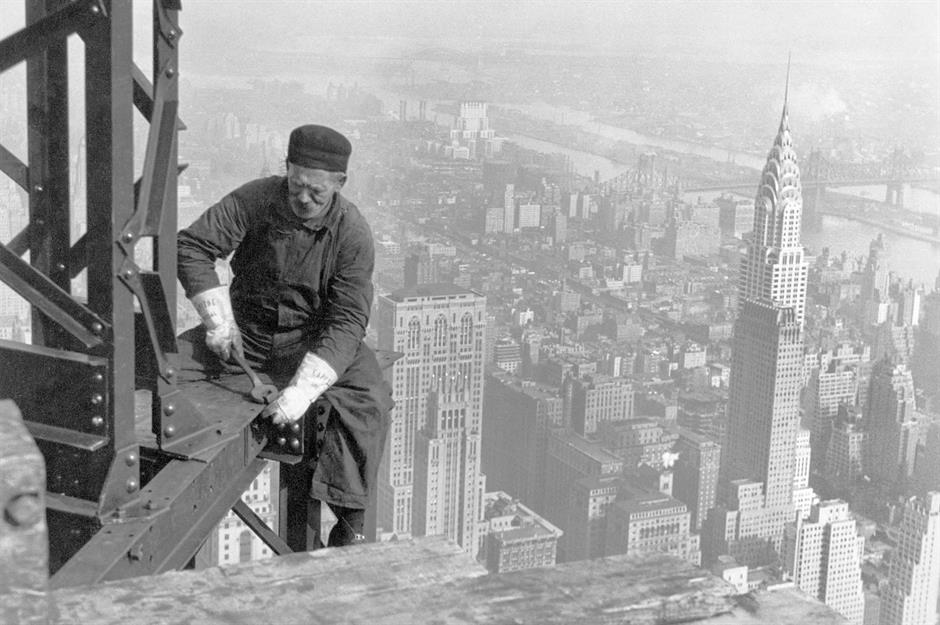

In the late 1920s, the competition heated up as New York’s economy experienced what was then its biggest boom in history. Among the main challengers in the skyscraper race were 40 Wall Street and the Chrysler Building (on the right in this 1930 image of an Empire State Building construction worker). Named after automobile magnate Walter P. Chrysler, the golden Art Deco tower eclipsed both 40 Wall Street (927ft/283m) and the Eiffel Tower to become the world’s tallest building in 1930, soaring to 1,046 feet (319m). However, the Eiffel Tower gaining an antenna in 1957 grew its total elevation to 1,083 feet (330m).

Sponsored Content

Art Deco dreams

But a third contender for the crown emerged when former General Motors executive John Jakob Raskob and previous New York Governor Al Smith joined forces in 1929 to announce plans for the Empire State Building (Smith is pictured here laying its cornerstone). They commissioned architects from Shreve, Lamb and Harmon for the design, with Raskob supposedly asking William Lamb to make the skyscraper as high as he could without it falling down. It’s said that Lamb drew inspiration from two notable Art Deco buildings in envisioning the ESB, the Reynolds Building in Winston-Salem (another of his creations) and Carew Tower in Cincinnati.

A futuristic feature

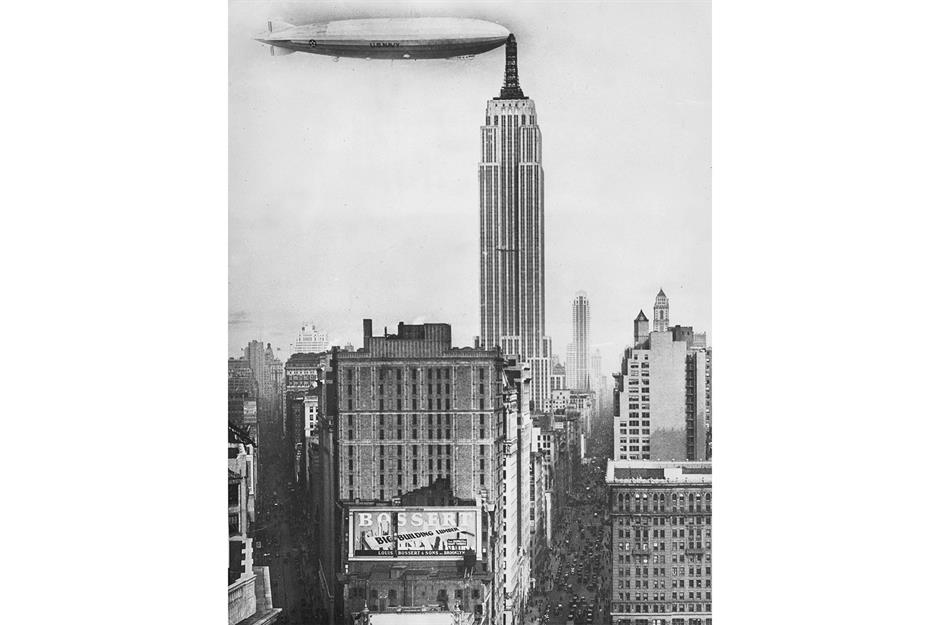

To create additional height without the bulk, Raskob suggested the Empire State Building (named after the nickname for New York State) might benefit from a 'hat'. This 'hat' became a 200-foot (61m) spire initially aimed to double as a docking station for airships, which were eccentrically believed to be the future of transatlantic travel. Despite intentions, the mast was only successfully used for that purpose once, when a small dirigible tethered itself to the ESB’s roof in September 1931. The high winds that swirl around the top of the building were found to make moorings practically impossible.

Clearing the way

To make space for the Empire State Building in the midst of the expanding metropolis, another iconic New York landmark was sacrificed. In 1929, Raskob and his partners bought the land on which the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel (pictured), located on Fifth Avenue and 34th Street, stood. With the estimated $20 million from the sale (£289m/$367m today), the hotel later reopened on Park Avenue, while its original shell was demolished, its contents auctioned off, and the foundations of the Empire State Building laid. On 17 March 1930, construction officially began on the ESB.

Sponsored Content

Up against it

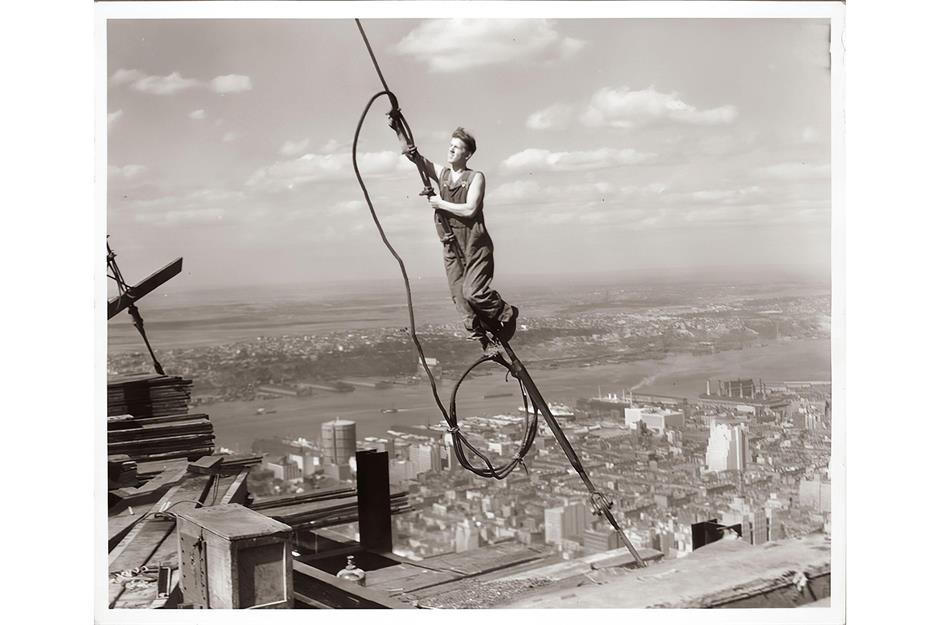

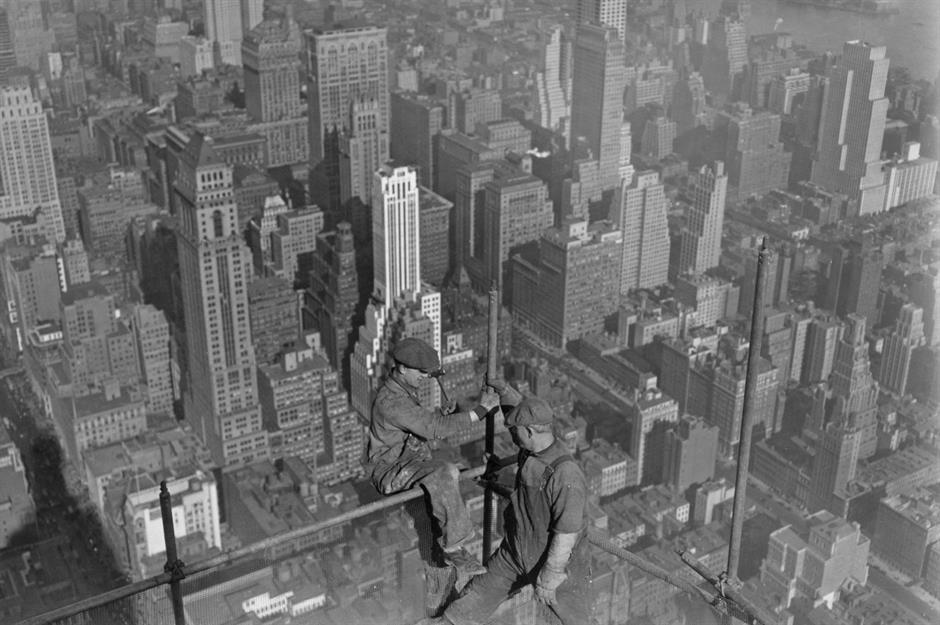

But in the time between Raskob and Smith making their announcement in August 1929 and building work commencing, the Wall Street crash happened. Pitching America towards the Great Depression, it triggered the deepest and longest-lasting economic slump the Western industralised world had ever seen at the time. Yet construction on the Empire State Building continued apace, providing vital jobs to labourers in NYC. Photographer Lewis Hine famously captured some of the process, showing steelworkers in action as they toiled away at dizzying heights. This shot he called Icarus.

Work in progress

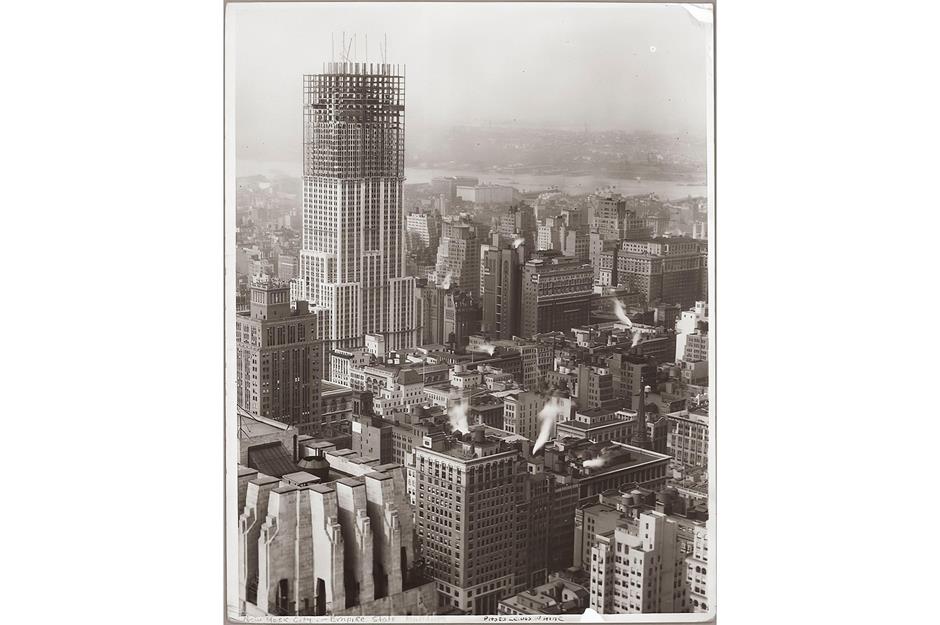

Building contractors Starrett Bros. and Eken – as well as impressing with their experience and insight – won the bid for the construction job by promising Raskob they could have the Empire State finished in 18 months. Poised to be the world’s first 100-plus-storey building, the ESB’s Pittsburgh steel skeleton rose by an average of four and a half storeys per week. To make the vertical frame, 210 steel columns were used. While most of them were divided into smaller sections, 12 of the rods ran all the way up to the mooring mast.

Love this? Follow us on Facebook for more history and travel features

Man power

As many as 3,400 labourers, including European immigrants and Native North Americans, worked on the ESB on any given day. Crowds swarmed in the streets below to watch the men “crawling, climbing… swooping on gigantic steel frames,” as reported by London’s Daily Herald. The riveters put on quite the show too; working in teams of four, one would heat the rivets and toss them to another, who would catch the red-hot rivets in a can and place them into their holes. A third man then supported the rivet while another hammered it into the beam. They repeated this process from ground level to the 102nd floor.

Sponsored Content

A coordinated effort

To maximise efficiency during construction, a railway – whose carts could carry eight times the load of a wheelbarrow – was established at the site to ferry building materials. Enormous cranes lifted steel girders to the upper storeys, while the 10 million bricks required for the skyscraper were stored in a basement hopper, so as not to clog up the surrounding streets. While all of that was going on outside, the building’s interior was a hive of electricians, plumbers and decorators making the Empire State ready for tenants. Sadly, this immense project was not without a human cost: at least five workers died during the ESB’s construction.

Opening day

After a record-fast 410 days (13 and a half months) of construction and seven million man hours of hard graft, the completed Empire State Building was unveiled with great ceremony. On 1 May 1913, President Herbert Hoover pressed a button in Washington DC to switch the tower’s lights on for the very first time. Meanwhile in NYC (pictured), a ribbon was cut, city mayor Jimmy Walker gave a speech, and the skyscraper was officially opened. Finished on schedule and under budget (due to the Great Depression lowering labour costs), the Empire State Building’s total price tag was $40,948,900 (£669m/$846m today) – well below the expected $50 million.

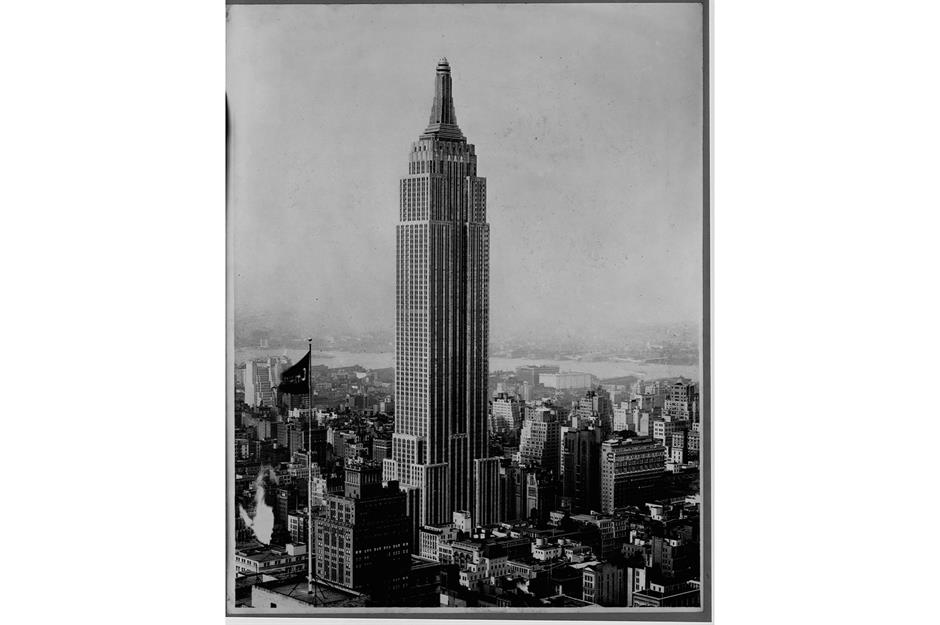

The world’s tallest building

On completion, the Empire State became the world’s tallest building, towering at 1,250 feet (381m) to the top of its spire. Its weight of 365,000 tonnes included 730 tonnes of stainless steel and aluminium, as well as 200,000 cubic feet of Indiana limestone and granite. It retained the title of world’s tallest man-made structure for nearly 40 years, until the first World Trade Center tower was finished in 1970. Its current height is 1,454 feet (443m, courtesy of a new antenna fitted in 1985), making it the fourth tallest building in New York City, the sixth tallest in the US, and 43rd tallest tower on Earth.

Sponsored Content

ESB in numbers

The Empire State Building sits on a two-acre base and rises up to 103 floors, though it’s VIP access only on its very top floor. From street level, 1,860 steps snake up to the 102nd floor, but there are also 73 huge elevators on hand if you need them. In-keeping with the Art Deco movement's love of vertical lines and geometric shapes, the vast skyscraper boasts 6,514 windows – all of which need regular cleaning. This vertigo-inducing photograph from 1932 shows a team of fearless window washers suspended above 34th Street.

A cinematic superstar

Though fundamentally a corporate office building, it wasn’t long before NYC’s newest skyscraper was taking on more glamorous roles. It caught the eye of Hollywood not long after opening: in 1933, a model of the Empire State Building featured in the pioneering monster movie King Kong (pictured), which spectacularly ends with the titular gorilla clinging to its spire while fending off biplanes. Since then, the landmark has appeared in more than 90 movies, including the epic romances An Affair to Remember and Sleepless in Seattle.

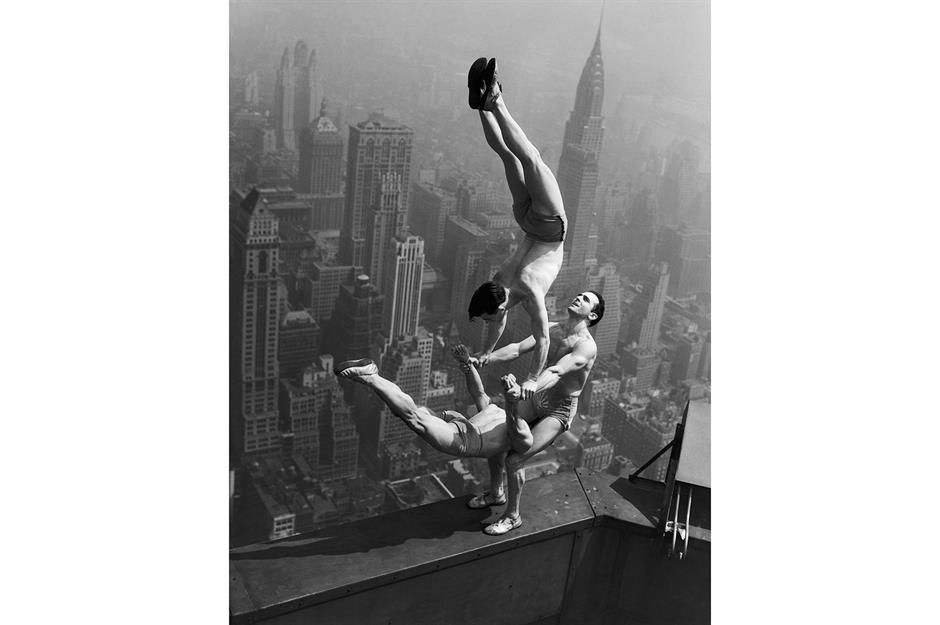

Balancing act

Word of the Empire State Building’s majestic architecture and unbeatable views travelled fast. Within six months of opening to the public, the building amassed more than $3,000 (£49k/$62k today) from visitors paying 10 cents for a glimpse of the NYC skyline through one of the ESB’s telescopes. But it wasn’t just tourists going to great heights – this image from 1934 shows the ‘Three Jacksons’ acrobatic troupe entangled in a death-defying stunt on the ledge of the skyscraper’s 86th floor. The act, performed with no harnesses or safety net, remains the only instance anything like this has ever been allowed at the ESB.

Sponsored Content

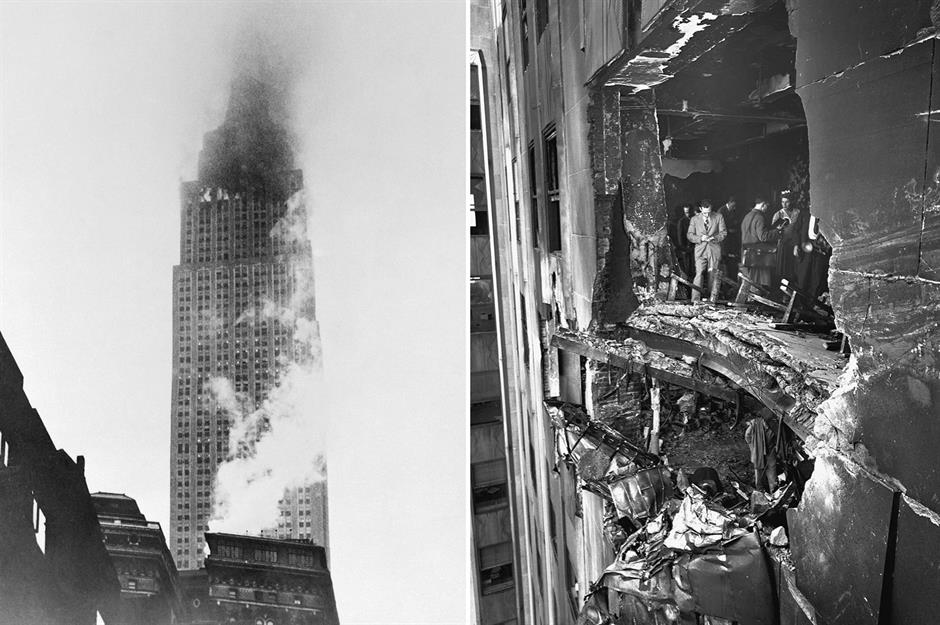

Trying times

As time wore on and the Great Depression intensified, the Empire State Building could not escape its effects. Reams of its rentable square footage were left unoccupied, with the so-called ‘Empty State Building’ taking until 1950 to turn a profit. Even worse circumstances hit the tower on 28 July 1945, when dense fog caused a US Army B-25 bomber to crash into its 78th and 79th floors (aftermath pictured here). There were 14 fatalities, including the pilot and his crewmen. The consequent explosion set a blaze burning on several floors, but this was extinguished within 40 minutes by the fire service. The undamaged parts of the building reopened two days later.

Modern marvel

The 1950s were far more peaceful and prosperous for the ESB. Gaining wide recognition as an architectural, structural and cultural marvel, the skyscraper went from strength to strength. It was topped with its first new antenna in 1950 (pictured), which increased the building’s height to 1,472 feet (449) for the next 35 years of its life. In 1955, the Empire State joined the likes of the Panama Canal and the Hoover Dam to be pronounced one of the seven greatest engineering feats in US history, as decided by the American Society of Civil Engineers.

ESB in the 1960s

The Empire State Building had an eventful decade in the 60s. Pictured here in 1962, it was bought by Lawrence A. Wien, Peter L. Malkin and Harry B. Helmsley for $65 million (£540m/$683m today) the previous year – a cost which didn’t include the land beneath it, making this the most expensive purchase ever of a single building. In 1969, it served as the finish line for the Daily Mail Transatlantic Air Race from London to New York, an event marking 50 years since the first nonstop flight across the Atlantic.

Sponsored Content

Lighting it up

In 1976, the Empire State Building welcomed its 50 millionth visitor. This was also the year of the United States Bicentennial, which saw the landmark’s top 30 floors floodlit with colour for the very first time. The ESB’s lights, upgraded to LEDs in 2012, can now glow in 16 million different colours. They shine for annual celebrations and holidays, for notable anniversaries and sporting events, but also to raise awareness for social and charitable causes. At the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, they pulsed red and white in tribute to emergency workers. The full calendar for the tower lights schedule can be viewed online.

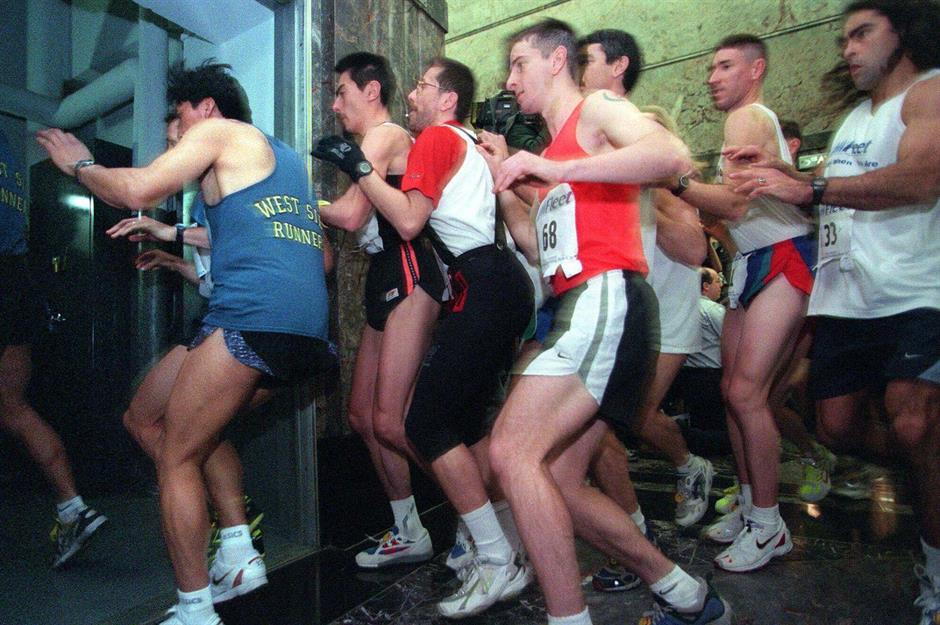

Run for glory

Two years after the Empire State gained its famous lights, a yearly tower tradition was born. On 15 February 1978, the inaugural Empire State Building Annual Run-Up was held, challenging racers to sprint up the 1,500-plus steps to the skyscraper’s 86th floor. The event continues to this day – 2023 marked its 45th year, making this the longest-running and most famous tower race in the world. More than 300 people typically take part, from elite athletes to celebrities, with places decided by a lottery.

Skyline views

No visit to the Big Apple would be complete without a trip up to the Empire State Building’s observatories. The landmark’s 86th-floor observation deck, with its open-air balcony, (now free) telescopes and 360-degree views, offers sightings of the Hudson and East Rivers, Brooklyn Bridge and the Statue of the Liberty. From the 102nd floor, which wins the silver medal for NYC’s highest observation deck, you can see as many as six states on a clear day – New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Connecticut, Massachusetts and Delaware. This level is enclosed with floor-to-ceiling windows.

Sponsored Content

A landmark lobby

But it’s not just the views that are spectacular. The skyscraper’s gorgeous Fifth Avenue lobby is one of only a few interiors in New York to be designated a historic landmark. Gilded with gold and shiny with marble, it’s entirely befitting one of the world’s most remarkable buildings. Among its most striking features is the celestial ceiling mural, decorated with classic Art Deco impressions of stars, sunbursts and gears. After being covered with a dropped ceiling in the 1960s, the mural was painstakingly and precisely recreated between 2007 and 2009 – a process taking longer than the ESB’s original construction.

‘A city within a city’

Did you know the Empire State has its very own zip code? Holding over 2.7 million square feet (250,838sqm) of office space, it’s one of the largest office buildings in the world, where businesses like LinkedIn, Shutterstock and JCDecaux North America all have premises. As well as its own zip code (10118), the Empire State Building also has its own post office on the second floor. But what else is inside? In addition to its observatories, corporate offices and public exhibitions, you’ll find a selection of shops and restaurants within the skyscraper, including a three-storey Starbucks Reserve.

Artist in residence

In October 2017, the 80th floor of the Empire State Building hosted British artist Stephen Wiltshire (pictured) while he sketched a panoramic pencil drawing of the New York City skyline. But this was no ordinary piece of art; Wiltshire, having taken just a 45-minute helicopter flight above Manhattan, then drew his cityscape completely from memory. A live audience watched over the course of five days as he flooded the canvas with astonishing detail. The finished drawing is on display at the ESB and can also be viewed online.

Sponsored Content

Greening the ESB

As it has become increasingly important for even heritage buildings to operate more sustainably, the Empire State Building recently underwent an immense 21st-century retrofit that took more than 10 years to complete. This project saw the energy efficiency of the ESB vastly improved: every single one of the skyscraper’s 6,514 windows were replaced, quadrupling the energy performance and ensuring over 96% of the existing materials were repurposed. Since 2011, the Empire State has also run entirely on electricity generated by wind power.

Love is in the air

Among its other accolades, the Empire State Building has also been called the world’s most romantic building. For several years beginning in 1994, the skyscraper held an annual Valentine’s Day contest to award lucky lovers the wedding of their dreams on the 86th-floor observatory (pictured). While these weddings no longer take place, more than 250 couples have exchanged their vows as part of the event. The ESB still keeps the romance alive in other ways, including giving away a $10,000 (£7,894) dinner experience, offering exclusive engagement packages and hosting themed movie nights. The tower lights glowed with a pink heartbeat pattern for Valentine’s Day 2024.

Caught on camera

Though it has since had to relinquish its status at the world's tallest building, the Empire State is scientifically proven to be its most photographed. Researchers from Cornell University came to the conclusion in 2011, having analysed millions of images of the iconic skyscraper. Some of the best photo opportunities occur on stormy nights – the ESB’s antenna is struck by lightning an average of 25 times a year, making for some seriously dramatic shots. Budding shutterbugs should also head to 34th Street, Williamsburg's waterfront Domino Park and DUMBO to capture the ESB's most photogenic angles.

Sponsored Content

Visiting today

Visitors to the Empire State Building are encouraged to book their tickets in advance, which can be easily done through the ESB website, though you can also book in person at one of the onsite kiosks. Either way, you’ll be allocated a timed entry slot and have the choice to visit just the 86th-floor observation deck, or the 102nd floor as well. But don’t just rush to the views – take some time to soak up the indoor museum and exhibitions too, which chart various phases of the landmark’s story.

Now check out these incredible photos of NYC from over a century ago...

Comments

Be the first to comment

Do you want to comment on this article? You need to be signed in for this feature