The incredible story of Yosemite – America’s most photogenic national park

A granite masterpiece

The crown jewel of the Sierra Nevada mountain range, Yosemite is one of California’s – and America’s – most precious landscapes. Located around 140 miles from the city of San Francisco, this spectacular site played a pivotal role in the shaping of America’s national park system, and is today one of the most popular national parks in the world. Here we chart its mesmerizing story, from its many natural wonders to modern man-made threats.

Click through this gallery to discover the history of Yosemite, and how to get the best out of your visit today…

Humans lived here long before national parks existed

Archaeological studies of Yosemite Valley show that Native Americans have lived in this part of modern-day California for around 5,500 years. The peoples of the Southern Sierra Miwuk Nation were the main Indigenous inhabitants of what is now the national park, with Yosemite translating as “those who are killers” in the language of the Miwuk.

This name refers to the Ahwahneechee, a mixed tribe including Miwuk and Mono Paiute peoples who resided in Yosemite Valley.

The Gold Rush changed everything

The natural sanctuary offered by the valley's seclusion afforded its Indigenous residents some protection against Mexican, Spanish and other European-American colonists, but the California Gold Rush of 1848 marked a troubling turning point in Yosemite’s history.

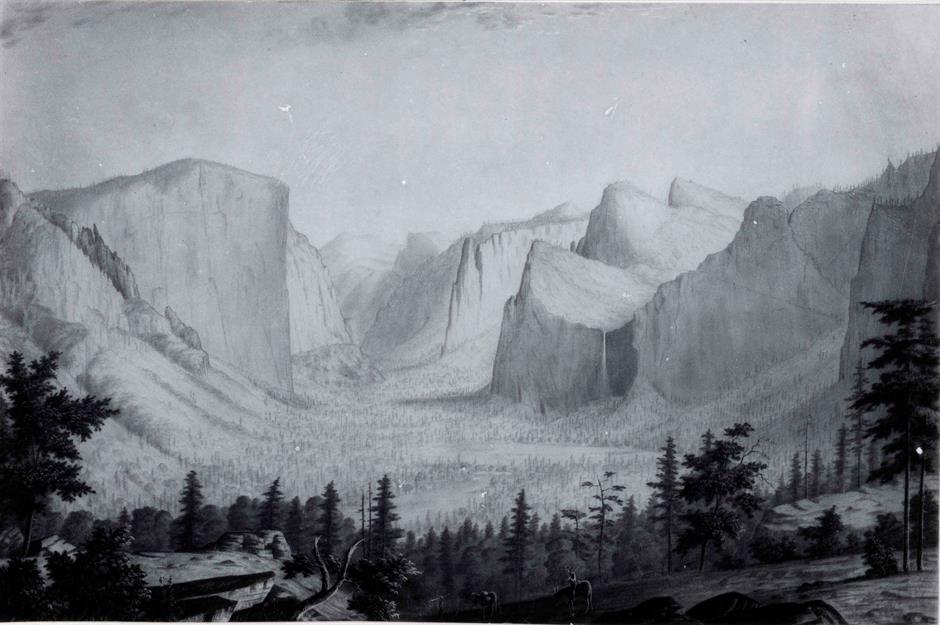

Thousands of miners and settlers descended upon the foothills of the Sierra Nevada, and tensions came to a head in 1851 when the Mariposa Battalion (sanctioned by the new state of California) burned the villages of the Miwuk peoples and took their ancestral lands. This 1855 drawing of Yosemite Valley is by Thomas Ayres.

The protection of Yosemite was a first for America

In the years that followed, continued commercial exploitation as a result of mining, animal grazing, and tourism gradually devastated the Yosemite Valley ecosystem. In 1864 a group of conservationists convinced President Abraham Lincoln to declare the valley, together with the Mariposa Grove of giant sequoias (pictured), a public trust of California.

This was the first time in US history that the government acted to protect land for public enjoyment – meaning that Yosemite paved the way for the national park movement.

But it wasn’t officially the country’s first national park

At the time of Yosemite’s designation as a national park on October 1, 1890, the American national park system was in its earliest days. Yellowstone became the country’s first official national park on March 1, 1872, followed by Mackinac Island three years later (though it was later reclassified as a state park).

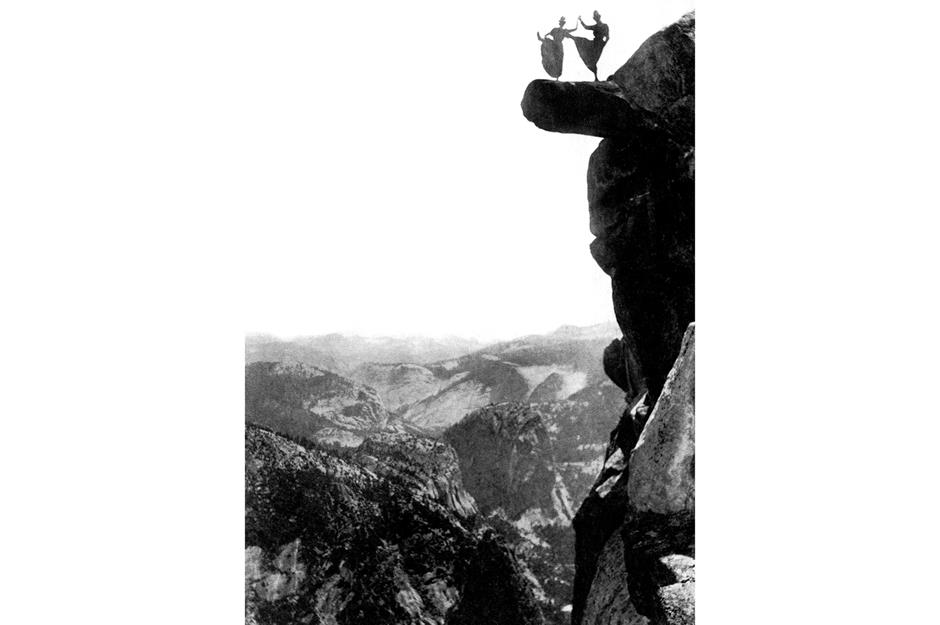

Sequoia National Park was then established on September 25, 1890 – a week before Yosemite. Here’s a photo from 1890 showing a couple of local waitresses dancing atop Yosemite's Glacier Point.

A Scotsman was instrumental in its foundation

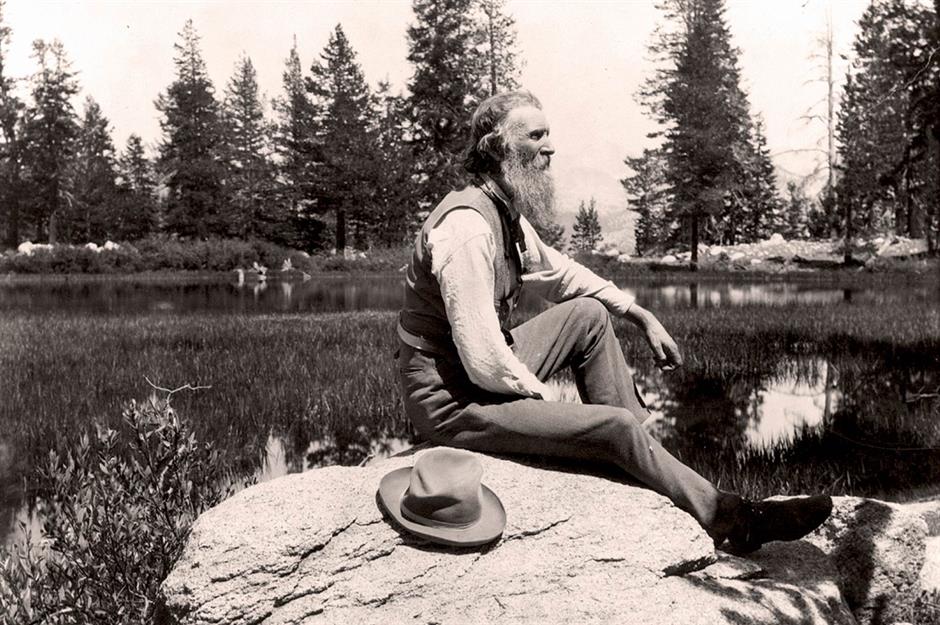

Yosemite’s inauguration came after the environmentalist John Muir and his colleagues lobbied for President Benjamin Harrison to save the meadows surrounding Yosemite Valley from unregulated sheep grazing in 1889, which had contributed to habitat damage and the spread of disease among native species.

Muir was born in Scotland but relocated to Wisconsin, and fell in love with the Californian countryside when he visited for the first time in 1868. He wrote that "no temple made with hands can compare with Yosemite." But the lauded conservationist remains a controversial figure given his use of racist slurs.

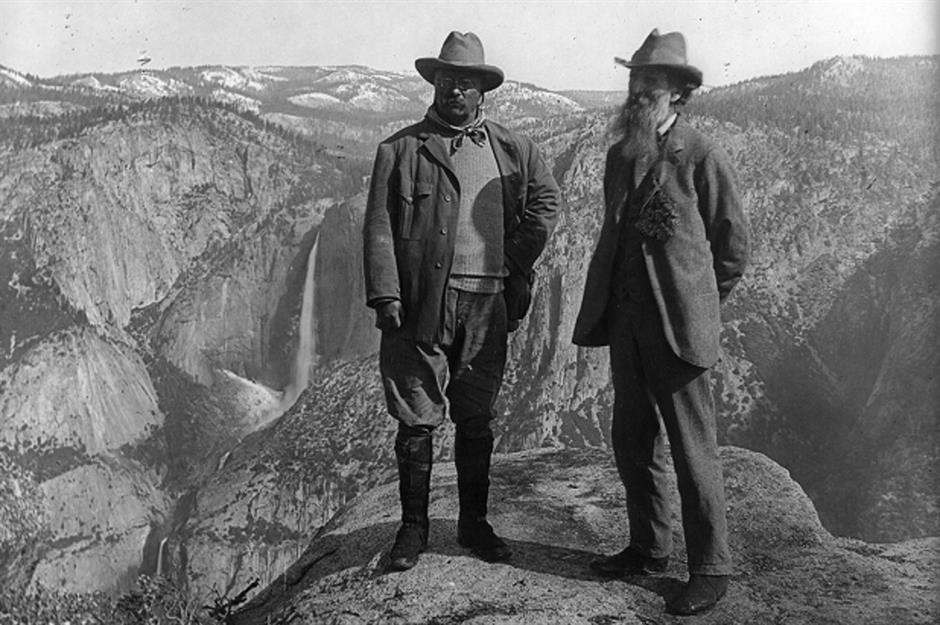

He took the president camping

In 1890, Congress allocated over 1,500 square miles of land (roughly the size of Rhode Island) for what would become Yosemite National Park. The state-controlled Yosemite Valley and Mariposa Grove were added to the park in 1906, after President Theodore Roosevelt traveled to California in 1903 and requested that John Muir join him on a camping trip.

Roosevelt, having slept under the gargantuan sequoias of Mariposa Grove, echoed Muir’s sentiments and compared the experience to "lying in a great solemn cathedral."

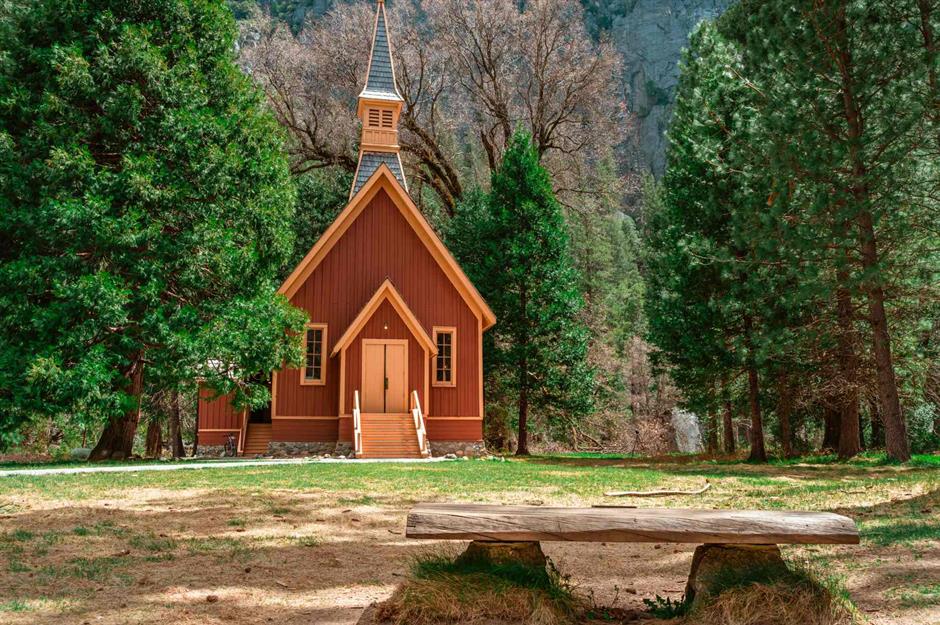

The park is home to one of California's original mountain resort hotels

One of the first accommodations in Yosemite National Park was the Wawona Hotel (pictured). The Victorian lodge still welcomes guests today and is a National Historic Landmark.

It is remembered as one of the Golden State’s original mountain resort hotels – Teddy Roosevelt famously visited – and is one of the only original hotels in Yosemite still standing. The earliest structure on the site, a humble log cabin, was built in the mid-19th century by former gold prospector Galen Clark, who was the first guardian of the Yosemite Grant.

Trails and tribulations

In the days before cars arrived in Yosemite, the journey here from San Francisco was nothing short of an expedition. It started with a boat to Stockton and continued with a rickety stagecoach to Mariposa or Coulterville, followed by a ride on one of several horse trails.

The establishment of more developed trails revolutionized travel to and through Yosemite: there are now roughly 800 miles of trails that knit through the park, with some of the earliest first trodden by Native Americans.

The road to greatness

The advent of roads in Yosemite began with wagon routes completed in the mid-1870s, with stagecoaches full of tourists filing into the park via three new toll roads. But in 1900, an automobile (the steam-powered "locomobile" pictured) chugged into the national park for the first time.

Annual visitors rose from around 3,000 in 1885 to over 30,000 by 1915, owing to the introduction of car access, more sophisticated highways and the (since discontinued) railroad. The number of yearly tourists surpassed half a million in 1940 and first breached the one-million threshold in 1954.

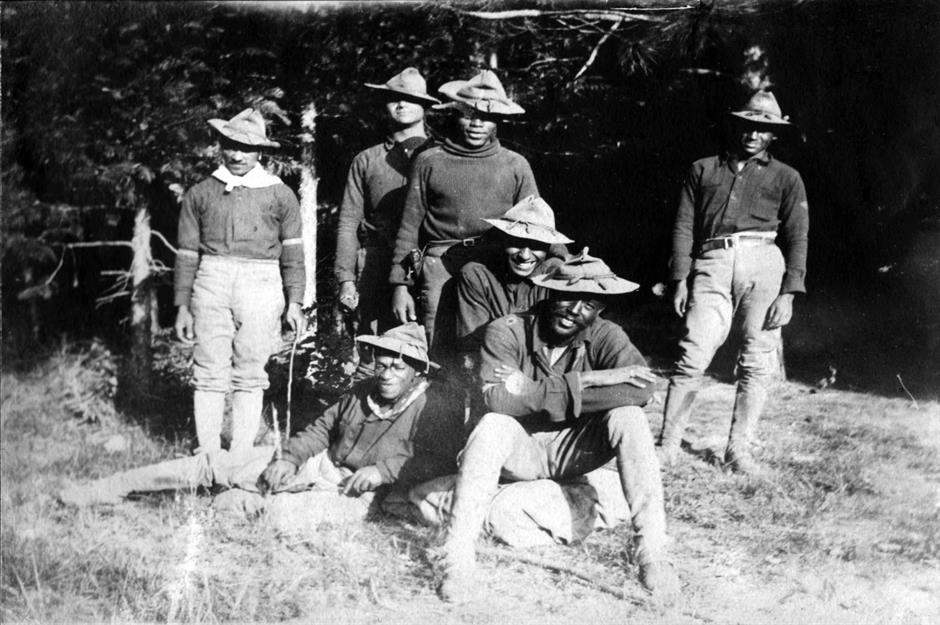

Buffalo soldiers pioneered the NPS ranger hat

Before the emergence of America’s National Park Service (NPS) in 1916, looking after Yosemite fell to the military, often to so-called buffalo soldiers. These men were African-American veterans of the Spanish-American War who, while serving overseas in rainy conditions, had learned to pinch their domed, wide-brimmed hats into symmetrical quadrants to keep water out of their faces.

This "Montana Peak" style continued when the soldiers began managing Yosemite, and was eventually incorporated into the official NPS ranger uniform. Pictured are Buffalo soldiers of the 25th Infantry or the 9th Cavalry, while stationed at Yosemite in around 1899.

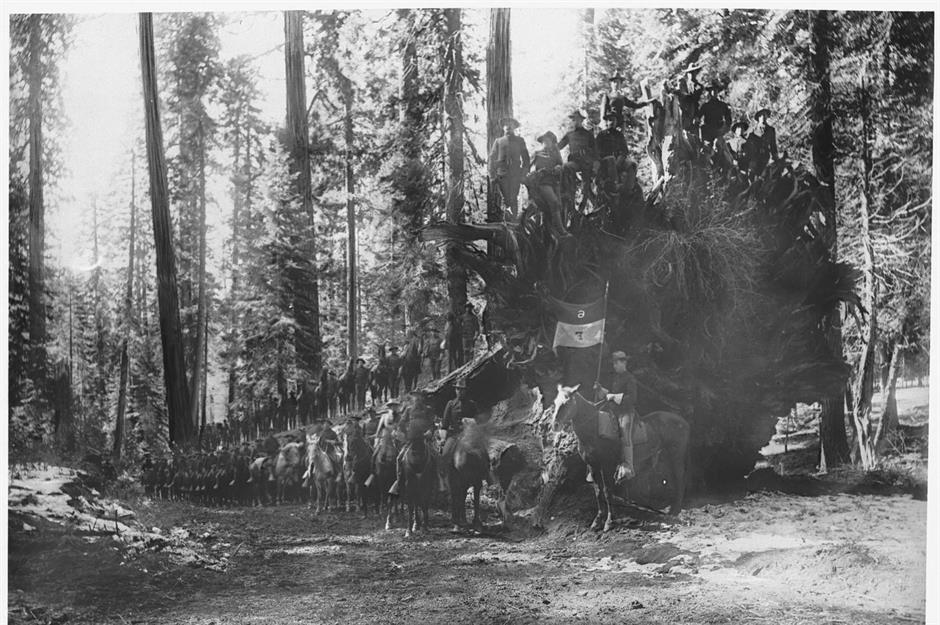

Rangers were vital to the protection and preservation of the park

This famous image from 1899 shows around 40 members from Troop F of the US 6th Cavalry posing with their trusted steeds in Yosemite National Park. The tree they surround is the Fallen Monarch, believed to have been toppled some 300 years ago; it still lies in Mariposa Grove today and can be seen along the Big Trees Loop trail.

Federal troops such as these helped police trespassing, livestock grazing, and clear-cutting in Yosemite between 1891 and 1913. In 1918, Clare Marie Hodges became the first female ranger to serve at the park.

Yosemite could have hosted the 1932 Winter Olympics

Inspired by his visit to the 1928 Winter Olympics, held in the Swiss resort of St Moritz, longstanding Yosemite grandee Don Tresidder spearheaded the national park’s bid to host the tournament’s next chapter.

To help market Yosemite as "the Switzerland of the West," an ice-skating rink, toboggan runs, a ski jump, and an 800-foot snow slide were created specifically for the campaign. However, along with several other American candidates, Yosemite lost out to Lake Placid in New York.

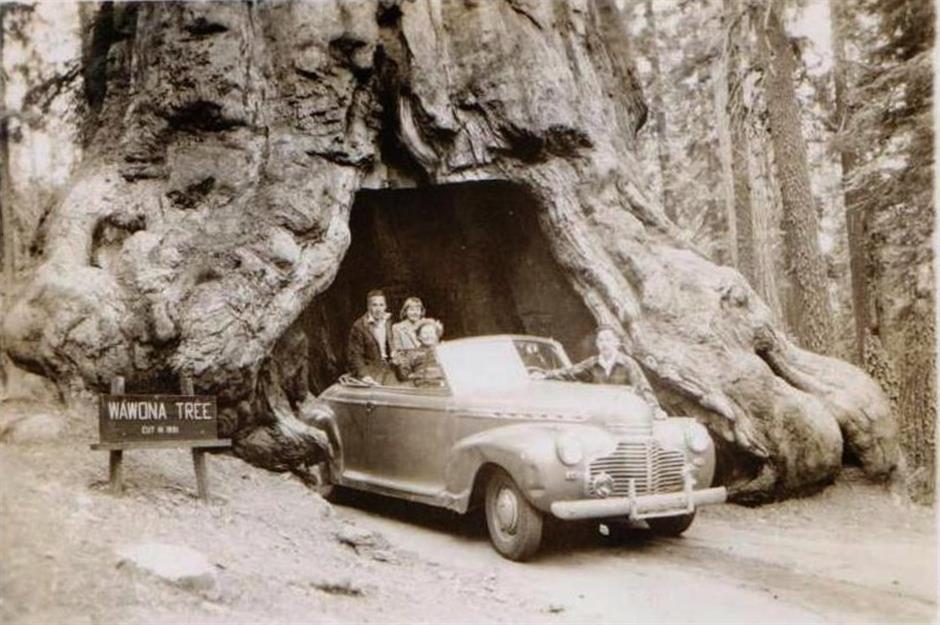

The dark side of tourism

Through the 1960s Yosemite felt the weight of its reputation as an increasingly sought-after tourist destination. Eighty-eight years after a tunnel was cut through its trunk as a visitor attraction and photo opportunity, the Wawona Tree (pictured here in 1946) fell during the winter of 1968-69.

The national park was also a known gathering place for nature-loving, free-spirited Californians, with one newspaper at the time claiming there were "more hippies than bears" in Yosemite.

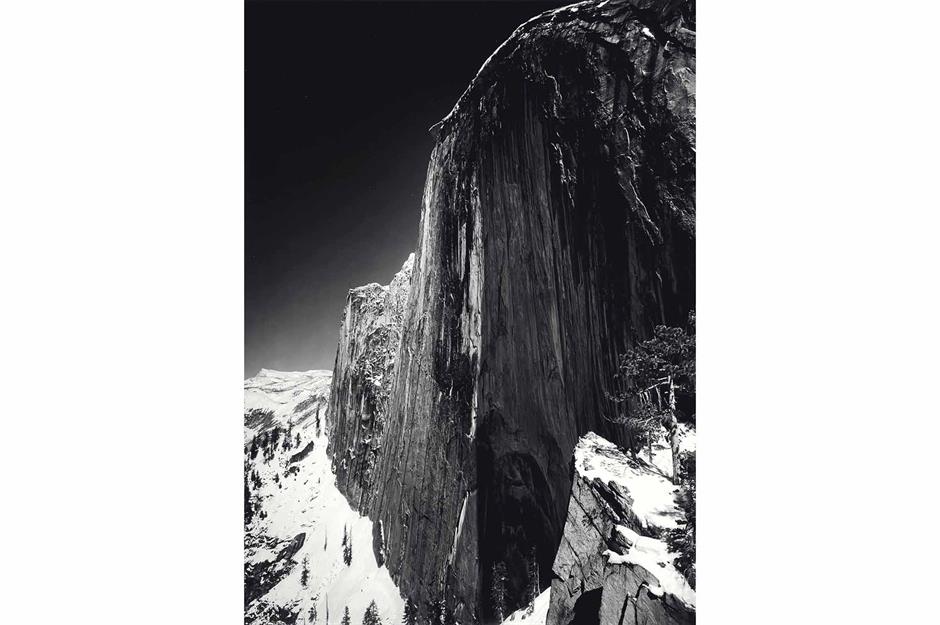

Yosemite: caught on camera

The beauty of Yosemite has captured the imagination of countless creatives down the decades. One of the most notable was the landscape photographer Ansel Adams (1902-1984), who dedicated years of his life to documenting the park.

His monochrome images of Yosemite – especially this one, Monolith, the Face of Half Dome, taken in 1927 – brought him immense critical acclaim. The Ansel Adams Gallery in Yosemite Village is still operated by the Adams family.

Other artists' impressions of Yosemite

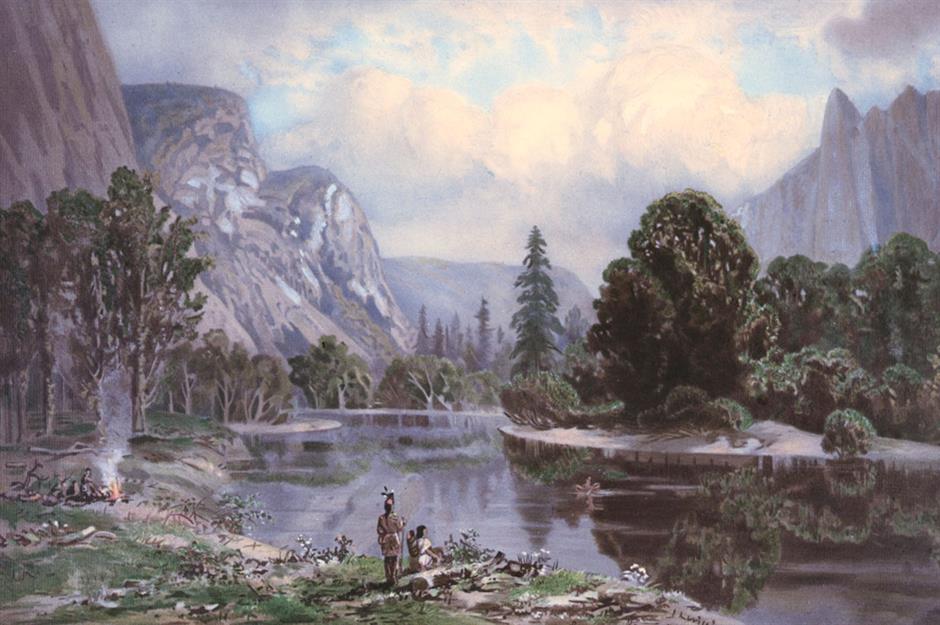

Images of Yosemite didn’t just help promote its stunning sights to the wider world, they also contributed to the foundation of the Yosemite Grant in the park's early history. Works by artists and photographers like Thomas Ayres, Albert Bierstadt, Thomas Hill, Carleton Watkins,and Charles Leander Weed were offered as evidence that Congress and President Lincoln needed to sign the grant into law.

Pictured here is an 1866 painting of Mount Starr King by Albert Bierstadt, who visited Yosemite in 1863 to make sketches, before returning to his New York studio to transform them into ethereal color scenes.

Its unique geology is recognized by UNESCO

While Yosemite’s human history dates back almost six millennia, its natural history is much, much older. Some of the granite rock formations that punctuate this scenic landscape date back more than 100 million years, born out of glaciers and eons of slow erosion that have also sculpted its yawning valleys.

Many of its tallest mountains exceed 10,000 feet, including Mount Lyell, which at 13,114 feet is the highest peak in the national park. This, along with the park's enormous waterfalls and towering trees, helped secure Yosemite World Heritage Site status in 1984.

A 21st-century restoration project split opinion

Announced in 2000, the big-budget Yosemite Valley Plan was the largest restoration effort to be mounted since the national park was declared in 1890. Its aim was to reduce human footprint in the park by pruning parking spaces, relocating campgrounds and roads, renovating accommodation, rebuilding houses wiped out by flooding, and improving shuttle buses.

It also included building wooden walkways over wetland meadows and demolishing an old river dam so water could flow freely again. While many welcomed the developments, others were critical of their impact on visitor freedom and archaeological sites.

What to expect today

Today, Yosemite National Park attracts well over four million visitors annually, who travel from all corners of the globe to see its towering trees, dramatic waterfalls, and majestic granite geology for themselves. There are five different entrances to the park – four on the western side and one, the Tioga Pass entrance, on the more remote eastern side.

Note that reservations for driving into or through the park and using its campgrounds are required at certain points in the year, so always check the NPS website ahead of your trip.

Meet the captain

El Capitan (pictured) is the literal rock star of Yosemite. Standing at more than 3,000 feet tall, this hulking granite monolith rises to more than twice the height of the Empire State Building. Another of the park’s most striking geological landmarks is Half Dome, nearly 5,000 feet above the valley floor, which can, like El Capitan, be climbed for unreal views over the majestic landscape.

To get Half Dome in the frame of your photo head to Glacier Point for the best perspective. Tunnel View, perhaps the most photographed view in the national park, features El Capitan, Bridalveil Fall, and Half Dome in the distance.

Admire gentle giants

Aside from mind-blowing rock formations, Yosemite is also renowned for its ancient sequoias. It’s believed that the oldest sequoia here could be more than 3,000 years old, and there are three groves of imposing, red-barked trees you can visit – Mariposa Grove, Tuolumne Grove, and Merced Grove.

One of the largest and best-loved residents of the Mariposa Grove is the affectionately named Grizzly Giant (pictured), estimated to be 2,900 years old. Giant sequoia trees can only be found on the western slopes of the Sierra Nevada, making the groves at Yosemite all the more enticing.

Bear witness to a commanding cascade

Yosemite Falls is an epic, triple-tier waterfall in the heart of the national park. One of the world’s tallest waterfalls, it has a combined drop of 2,425 feet and can be seen from a number of spots in the Yosemite Valley, with particularly good visibility from Yosemite Village and Yosemite Valley Lodge.

A one-mile loop trail leads visitors to the base of Lower Yosemite Fall, or you can hike right to the top if you have a whole day to spare and legs of steel. To catch Yosemite’s many waterfalls in full flow, time your visit for spring.

The fabled Yosemite "firefall" wasn't always a natural phenomenon

A tradition that began in the early 1870s, Glacier Point hotel owner James McCauley, having regaled guests with tales around the campfire, would then kick glowing embers over the side of the cliff, resulting in a fiery cascade. This put on a spellbinding show for the people below, who were soon paying McCauley for the experience.

This somewhat dangerous attraction continued on and off until 1968 when the NPS put a stop to it. However, on occasional February evenings, the water of Horsetail Fall seemingly turns amber when back-lit by the sunset, reminiscent of the historic practice.

It’s not the only rare spectacle in Yosemite

Visit the national park on a late-winter or early-spring morning and you might encounter frazil ice – an unusual phenomenon that occurs when ice crystals collect in freezing, turbulent waters. At Yosemite, it’s often caused by waterfall mist freezing mid-air and dropping into the park’s babbling creeks, before flowing downstream like cotton-white lava.

It’s difficult to predict exactly when frazil ice might appear, but Yosemite Creek, Ribbon Creek, and Sentinel Creek are some of the best places to glimpse it when it does.

Yosemite’s climate is changing

The national park has had some difficult recent years when it comes to extreme weather and natural disasters. In summer 2022, smoke from California’s devastating Oak Fire blew into Yosemite, turning its skies murky grey and marring its typically unspoiled panoramas.

Then came the winter of 2023 and an onslaught of historic storms that saw the park temporarily close after snowfall broke a 54-year-old daily record. Yosemite has been called "ground zero for climate change," with endangered wildlife species, shrinking glaciers, rising temperatures, and drought.

A vast percentage of Yosemite goes unseen by tourists

According to Visit California, 95% of those that come to Yosemite only see 5% of the park. Most of the park lies within the bounds of Tuolumne and Mariposa counties, and both areas boast abundant natural wonders, heritage-rich towns, and other appealing attractions.

To discover Yosemite’s best-kept secrets, it’s worth exploring beyond the famous Yosemite Valley and venturing deeper into these counties. So, if you’ve finished basking in the beauty of El Capitan, we’ve got some suggestions for where to go next...

Hetch Hetchy Reservoir

2023 marked the centennial of the Hetch Hetchy Reservoir and the O’Shaughnessy Dam, which were created following the 1906 San Francisco earthquake to serve the city with drinking water. While its purpose is practical, the reservoir also represents one of Yosemite's finest hidden gems.

Filling the valley of the same name (which stems from the Native American Miwuk word "hatchhatchie," meaning "edible grasses"), the artificial lake is surrounded by soaring silver cliffs and two of North America’s tallest waterfalls, Tueeulala and Wapama Falls. Hetch Hetchy is wonderfully peaceful, receiving only 1% of total park visitation.

Tuolumne Meadows

In 1870, the Tuolumne Meadows were overrun and over-grazed by as many as 15,000 sheep. But nowadays they form a diverse landscape that houses a remarkable number of vivid plant species.

Because of this, Tuolumne Meadows has emerged as a highly valued ecosystem and is one of the most visually satisfying places in Yosemite, offering its trickle of visitors a true back-to-nature experience. Rimmed on all sides by the park’s iconic granite peaks and domes, this subalpine meadow is a breath of fresh air.

Go deeper into the Yosemite counties

In both Mariposa County and Tuolumne County, remnants of the California Gold Rush are never far from view. Old mining hubs like Mariposa’s historic downtown and Groveland (pictured) stand today as living museums, peppered with historic courthouses, saloons, and inns.

But there are more modern attractions in and around the gateways to Yosemite too, such as the Yosemite Climbing Museum and Gallery in Mariposa. Opened in 2022, it displays fascinating artifacts, photographs, and memorabilia that avid rock climbers will love.

Learn about Yosemite's Indigenous peoples

The Mariposa Museum and History Center sets out to preserve and interpret local culture, with an emphasis on the Gold Rush and the region’s Native American heritage. You’ll discover what life was like for the Indigenous tribes living in Yosemite long before its national park status.

The museum’s collection includes an umacha – a traditional tipi-shaped house clad in cedar bark – and an array of intricately woven baskets. At the Indian Village of the Ahwahnee (pictured), a reconstructed Native American settlement features replicas of a ceremonial roundhouse, a Miwuk cabin, and a chief’s house.

Rest your head in a royal bed

Opened in the 1920s, the Ahwahnee Hotel has hosted presidents, monarchs, and Hollywood stars in its time, as well as inspiring aspects of the Overlook Hotel in the film adaptation of Stephen King’s The Shining.

Today's guests can book a stay in the Ahwahnee's Mary Curry Tresidder Suite, which is where the late Queen Elizabeth II stayed during her 1983 tour of California. The hotel was also used as a World War II hospital for those afflicted with shell shock.

Comments

Be the first to comment

Do you want to comment on this article? You need to be signed in for this feature