These ancient finds quite literally changed history

History makers

Historians studying the distant past must often rely on scarce and incomplete sources. Sometimes, archaeologists uncover a single find that turns everything we thought we knew about the past on its head. Roman coins have exposed a previously unknown emperor, Greek tablets have revealed a new language and a lost settlement in Canada proved that the Vikings made it to North America years before Columbus. Dig through these archaeological finds that changed history as we know it...

L’Anse aux Meadows, Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada

A discovery by a Norwegian couple in 1960 shattered the idea that Christopher Columbus was the first European to reach the Americas. Investigations at L'Anse aux Meadows, an 11th-century Viking settlement in Newfoundland, proved that Vikings crossed the Atlantic nearly 500 years before Columbus set sail. Once they'd landed in America, a small community of Vikings set up camp in sturdy wooden huts – though it’s unclear whether the site functioned as a trading base or a colony. Nowadays, recreated buildings help modern visitors picture what life was like when the Vikings came to North America.

Love this? Follow us on Facebook for more travel inspiration

Ancient bronze statues, Italy

A hoard of 24 Etruscan and Roman bronze statues were unearthed in late 2022 by archaeologists digging in an ancient religious sanctuary near the village of San Casciano dei Bagni. Dated between the second century BC and the first century AD, they depict gods and replicas of human organs which had been tossed into the thermal waters by devotees hoping to be healed. A local professor said the find would "rewrite history", as it provided evidence that the relationship between Etruscans and Romans was closer than previously thought; the two peoples even prayed together. There are plans to turn the site into an archaeological park and display the statues at a new museum.

Sponsored Content

Hoxne hand axes, England, UK

When antiquarian John Frere found flint hand axes in a 12-foot (3.6m) hole dug by brickworkers in Suffolk in 1797, he wrote to the Society of Antiquaries and ventured his belief that these axes were from a "very remote period indeed" – a controversial assertion when many still followed the Bible's suggestion that the world was only a few thousand years old. But Frere wasn’t wrong, and modern tests proved that the hand axes date back at least 370,000 years. The flint tools are now housed in the British Museum.

Children of Llullaillaco, Argentina/Chile

In a cave high in the Andes, straddling the Argentina/Chile border, the naturally mummified bodies of three children were discovered by archaeologists in 1999. They were drugged then sacrificed around 500 years ago as part of an Incan ritual, and reveal fascinating and previously unknown details about the Incas. For instance, the 15-year-old girl is believed to be a sacrificial virgin, separated from her family and elevated to high status among the priesthood until her death: a valuable insight into the important Capacocha harvest ceremony.

Sponsian coins, Romania

Finds that change history can often be controversial. Historians agree that a Roman coin hoard was found in Transylvania in 1713, but the jury is still out on whether one of the people featured on the coins was real. Some classicists rejoiced when they realised several of them bore the head of a hitherto unknown Roman emperor named Sponsianus, but others dismissed the coins as an elaborate forgery. Research from 2022 recently suggested that the Sponsian coins were legitimate after all. Decide for yourself at the Hunterian Museum in Glasgow.

Sponsored Content

Giza workers' cemetery, Egypt

Traditional Egyptology has long held that the pyramids were built by slaves working in back-breaking conditions – a view propagated by the classical Greek historian, Herodotus. But an ancient cemetery uncovered at the turn of the 21st century suggests the pyramids were actually built by labourers able to down tools at will. The cemetery revealed that those who died on the job were granted an honourable burial, close to the royal tombs they helped construct, with grave goods including jars of beer and bread to help them on the journey to the afterlife. Not quite the riches of pharaonic burials, but these generous gifts have changed our understanding of social class in the deserts of ancient Egypt.

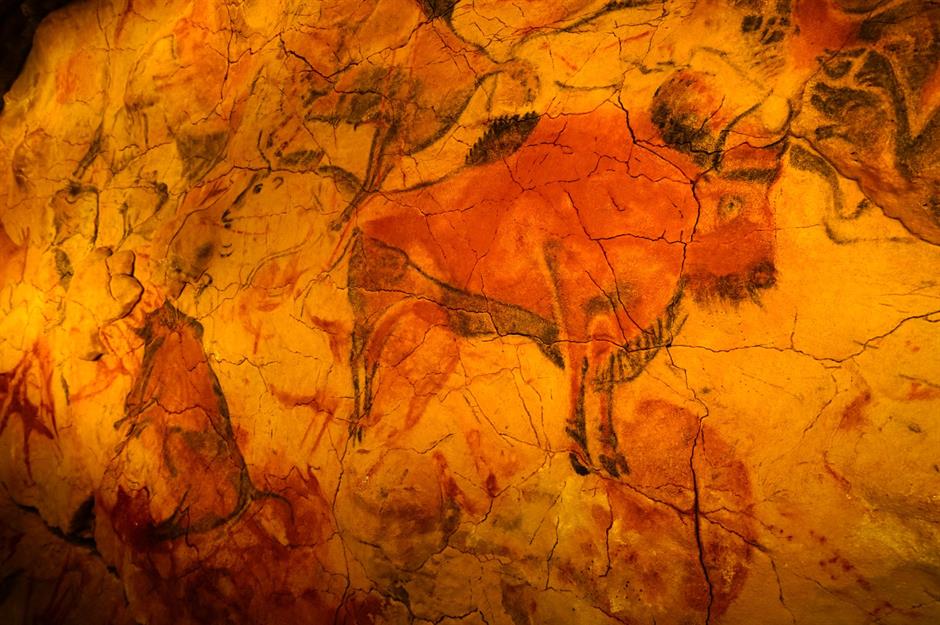

Cave of Altamira, Spain

An amateur archaeologist had been working in these caves in northern Spain for three years between 1876 and 1879, when his eight-year-old daughter looked up and noticed one ceiling was covered in pictures of bison, horses and wild boar. Until then, experts thought prehistoric people lacked the ability to create artwork, and the Cave of Altamira was the first example of Paleolithic cave art ever discovered. Access to the original is limited, but a precise replica of the cave paintings has been constructed at the National Museum and Research Centre of Altamira.

These amazing archaeological finds were stumbled upon by amateurs

Gobekli Tepe, Turkey

For a long time, historians thought the Neolithic Revolution – when humans stopped being nomads and started living in permanent agricultural settlements – occurred around 10,000 years ago. That consensus lasted until the 1990s, when archaeologists working at Gobekli Tepe in southern Turkey used radiocarbon dating to pinpoint the site's construction to 11,000 years ago, pushing the birth of human settlement further back into prehistory. Not only that, but some archaeologists working at Gobekli Tepe believe it may have been home to the world's first temple. It’s well worth a trip to Turkey to see a monument twice the age of Stonehenge.

Sponsored Content

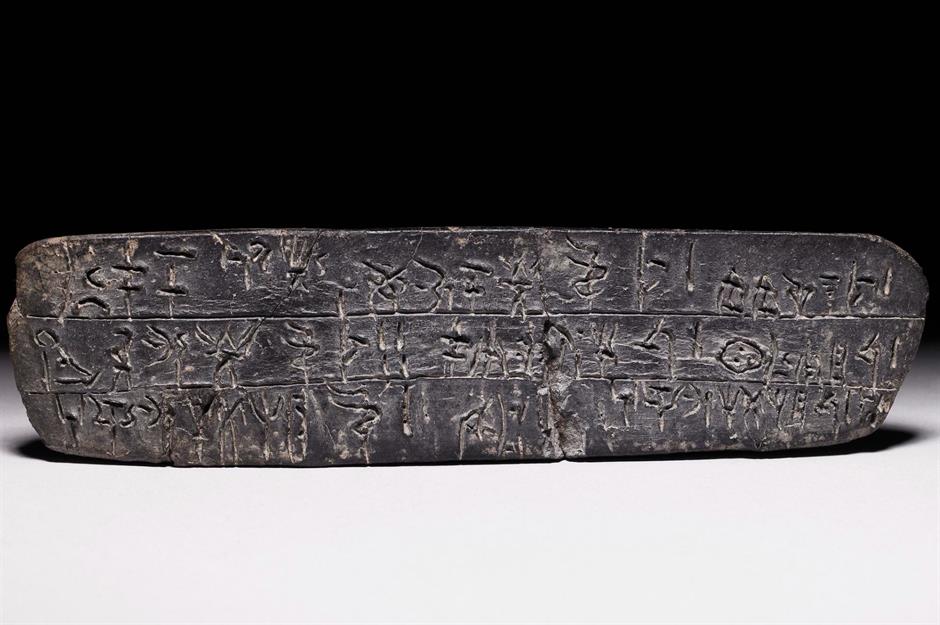

Knossos tablets, Greece

Early 20th-century excavations at Knossos on the Greek island of Crete revealed a wonderful Bronze Age palace with over 1,000 rooms, but perhaps the most important artefacts plucked from the dirt were thousands of baked clay slabs. These seemingly mundane tablets were cleaned up to expose a never-before-seen language, Linear B, used by the ancient Minoans. In 1952 it was finally deciphered (by an unusual duo comprising an enthusiastic architect and a young Cambridge linguist), making Linear B the oldest comprehensible language in Europe. Try to decipher the tablets yourself at Knossos or the British Museum.

Akrotiri, Greece

More than 1,500 years before Pompeii, the city of Akrotiri on Santorini was buried by a volcano in 1450 BC. Then, while digging for building material for the Suez Canal in 1860, an incredible snapshot of life in the Minoan era was uncovered. Archaeologists discovered something new: that the Bronze Age civilisation had the ability to construct three-storey buildings and dig complex drainage systems. The only thing missing from Akrotiri are its inhabitants – no human remains were found, suggesting the entire population was evacuated before the massive eruption. Wander Akrotiri’s deserted streets for yourself at the Museum of Prehistoric Thera.

Check out Pompeii's secrets that are only just being uncovered

Neanderthal jewellery, Spain

It’s tempting to think of Neanderthals as the brutish cousins of Homo sapiens, but archaeologists think a beautiful collection of decorative shells in a cave in Spain actually has Neanderthal origins. The shells have been coloured and perforated, suggesting they were worn as body ornamentation. As a result of this intriguing find, we're ever closer to understanding the Neanderthals – it proves they had the capacity to think symbolically and create art 50,000 years ago.

Sponsored Content

Vindolanda huts, England, UK

Vindolanda Roman Fort is famed for its wooden writing tablets, a set of 780 texts that enormously enhanced our understanding of what life was like as a Roman soldier in Britain. However, it's also known for a set of Celtic-style huts, the first example of native Britons living and interacting with the Roman invaders following the conquest. Perhaps more importantly, their design shows that even mighty Rome could be influenced by those it conquered. Excavations at Vindolanda occur every summer, so visitors have a chance to see the next history-changing find plucked out of the soil.

Discover the incredible little-known Roman ruins around the world

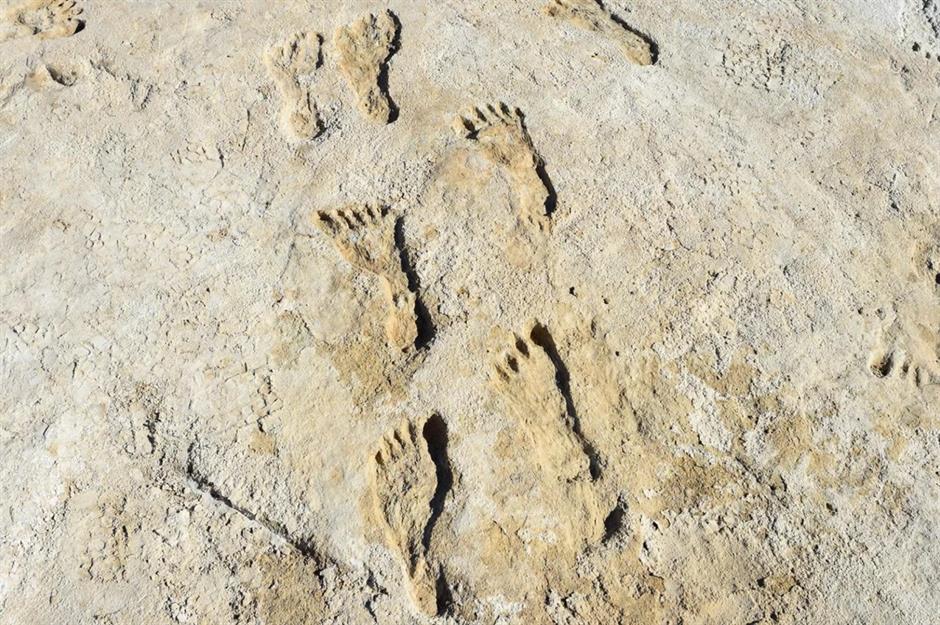

White Sands footprints, New Mexico, USA

As the name suggests, White Sands National Park in New Mexico is hot and dry – but it wasn’t always so. Around 23,000 years ago a lake sat in what is now Tularosa Basin, and humans left footprints in the wet mud as they skirted its shore. These wanderers even interacted with Ice Age mammals, such as mammoths. When their fossilised footmarks were discovered in 2021, it pushed back the earliest known arrival of humans in the Americas by up to 10,000 years. The footprints appear and disappear with the shifting sands, but replicas of the trackways are always on view at a visitor centre.

Durrington Walls, England, UK

Investigations at Durrington Walls – a larger, if less spectacular, Neolithic henge a couple of miles from Stonehenge – offer a new theory as to the true purpose of England's iconic stone circle. In 2015, radar scans of the area hinted at the existence of 90 giant stone monoliths buried underground in a C-shape, leading some archaeologists to dub the entire area a 'super-henge' – a vast site used for practicing spiritual rituals to do with life and death (not just death, as was thought likely at Stonehenge). The recent discoveries have prompted further research into the history of the entire region.

Sponsored Content

Hand of Irulegi, Spain

In 2021, archaeologists unearthed this 2,100-year-old bronze relic in Navarre, northern Spain. The Hand of Irulegi once belonged to the Vascones, a late-Iron Age tribe, and was most likely hung over a door for good luck. During its restoration in 2022, a four-line inscription was found etched into the hand, and the words are now believed to be the earliest ever written in the Basque language, arguably Europe's most unique modern language. Before the discovery, it was thought that the Vascones were mostly illiterate.

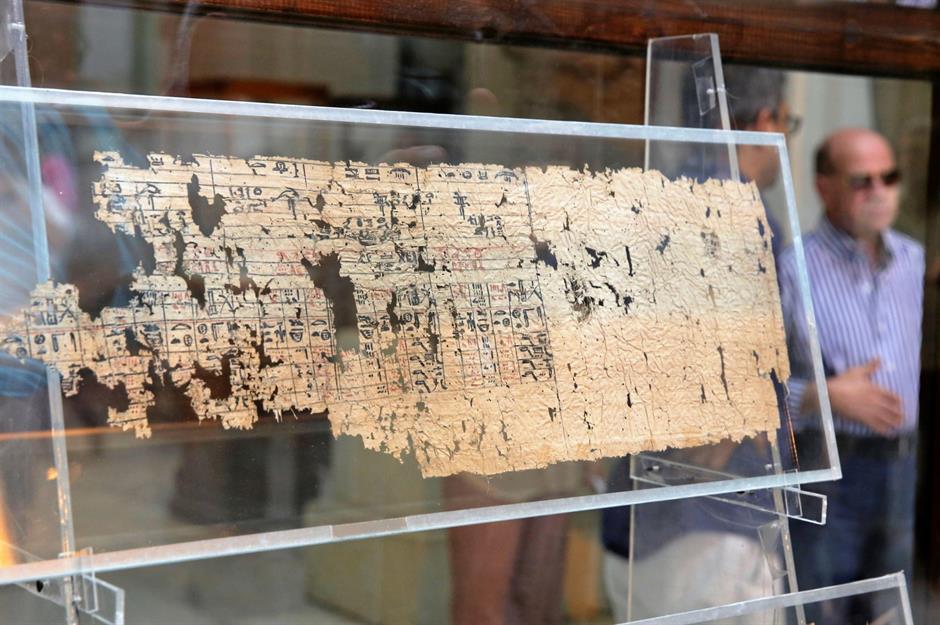

Wadi al-Jarf Papyri, Egypt

Archaeologists excavating the ancient Egyptian harbour – possibly the world's oldest known port – at Wadi al-Jarf in 2013 found a collection of well-preserved papyri that details not only how the pyramids were built but who built them, a mystery that has long puzzled archaeologists. One papyrus, the Diary of Merer, reports that a vizier named Ankhhaf was in charge of the pyramid’s construction. It also details daily working life at the building site, where skilled workers were well-treated – contradicting the commonly-held belief that the pyramids were built by slaves. The papyri are on display in Cairo, a few miles from the Great Pyramid.

Kilwa Coins, Northern Territory, Australia

Thanks to a handful of old coins, it's now possible that Indigenous Australians met outsiders much earlier than previously thought. In 2014, Australian researchers scouring museum storage rooms found some old coins originally picked up on a Northern Territory beach during the Second World War. The researchers soon realised that these coins were 900 years old and hailed from the Kilwa Sultanate, once a thriving maritime nation based on East Africa's Swahili coast. The coins suggest that medieval merchants travelled all the way to Australia, meaning Yolngu Aboriginals had some form of contact with the wider world six centuries before Captain Cook.

Sponsored Content

Creswell Crags, England, UK

In 2003, researchers were surveying caves in Nottinghamshire when they spotted faint engravings high up the walls. It was the first time that prehistoric cave art had been found in Britain, proving that the nomadic tribes of Britain had a similar enthusiasm for art and culture as the peoples who produced the more famous cave art of southern Europe. The engravings aren’t easy to see with an untrained eye, but guided tours help offer a glimpse into Britain’s distant past.

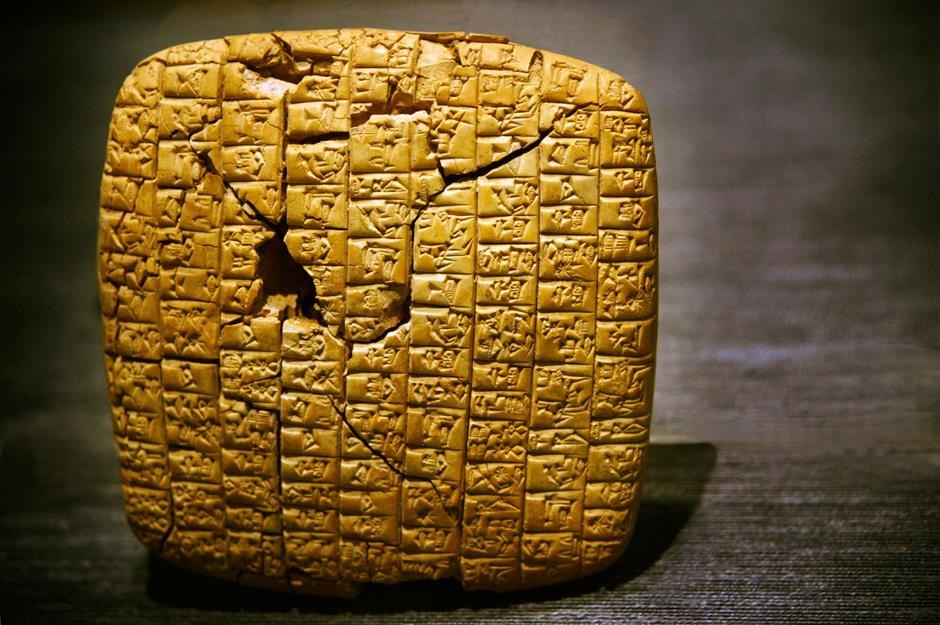

Ebla Archive, Syria

A wall collapsed at a Syrian archaeological excavation at the ancient city of Ebla in 1974, and beneath it was a 4,000-year-old archive of clay writing tablets bearing cuneiform script, a Bronze Age writing system used in the Middle East. The tablets were incredibly well-preserved, and still arranged on shelves in order of subject, making it one of the world's oldest libraries. The scholarly discovery gave historians an insight into just how advanced the Bronze Age people of this region were; the area was previously thought to have been a barren wasteland. The tablets are now kept in museums in Aleppo, Damascus and Idlib.

Rimini Surgeon’s House, Italy

Digs below the Piazza Ferrari in Rimini in 1998 revealed a surgeon’s house containing over 150 medical instruments – the most complete collection of surgical apparatus from the ancient world. The surgeon may have been a Greek military doctor and made use of remarkably modern implements for bone trauma and wounds, including a specific tool to root arrowheads out of the body. We knew the ancient Greeks were good at medicine – the Hippocratic oath that doctors take today is testament to that – but this find showed just how advanced their tools and methods were.

Sponsored Content

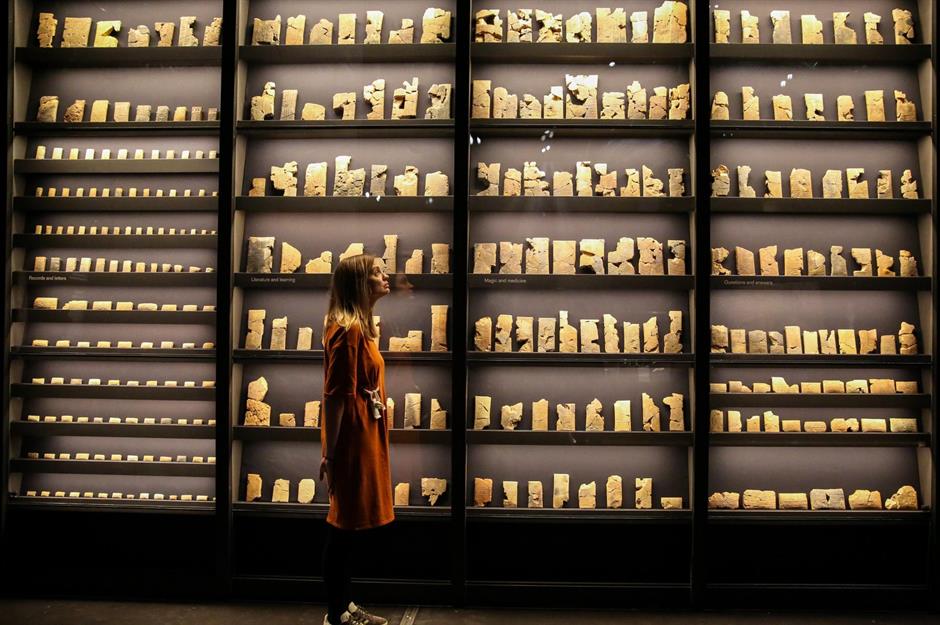

Library of Ashurbanipal, Iraq

In the 1850s, archaeologists working in modern-day Iraq found a batch of inscribed clay tablets that belonged to Ashurbanipal, a ruler of the Assyrian Empire in the 7th century BC. More than 30,000 pieces of writing were found, from administrative documents and medical textbooks to literary works like the Epic of Gilgamesh, an ancient Mesopotamian poem. This discovery gave modern historians access to an entire library of information about life in ancient Assyria, meaning they no longer needed to rely on often-inaccurate contemporary sources (such as the Bible and classical Greco-Roman historians). Some of the tablets are now on display in the British Museum.

Queen Neith, Egypt

Everybody is familiar with the pyramids of Giza – but a little to the south is another burial ground used by Egyptian royalty, the Saqqara complex. Among the most recent finds is a cache of 300 coffins and over a hundred mummies, including the remains of Tutankhamun's advisors and a previously unknown wife of pharaoh Teti, Queen Neith. The timeline of Egyptian royals is often incomplete or unclear, so Neith’s discovery fills another gap: top Egyptologist Zahi Hawass claimed it "rewrites what we know of history".

Misliya Cave Jawbone, Israel

In 2002, a student at his very first excavation found a fossilised human jawbone in a cave on Mount Carmel in Israel, but the find was kept quiet for 16 years while his supervisors sought to prove an earth-shattering theory. In 2018, they finally went public with their conclusions – the jawbone, itself up to 194,000 years old, was found alongside flint flakes that were as old as 250,000 years, meaning that Homo sapiens actually left Africa 50,000 years earlier than previously thought. A jaw-dropping discovery.

Sponsored Content

Troy, Turkey

For hundreds of years, classicists regarded the epic stories of Homer as just that: stories. That all changed in 1870, when excavations led by celebrity archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann began at an old city near Hisarlik, Turkey. Shortly afterwards, archaeologists excitedly announced they’d found the lost city of Troy, suggesting that the epic tales of wooden horses and women so beautiful they could launch ships had a basis in reality. The extent to which the ancient city matches up with the Troy of legend is up for debate, but it was inhabited for thousands of years and you can still wander its streets today.

Holmul Frieze, Guatemala

Archaeologists exploring the Maya city of Holmul in 2013 found a gigantic piece of wall art that yielded a lot of new information about the Maya. Around the outside of one building they uncovered a 26-foot (8m) stone frieze telling a religious story. Closer examination revealed that the frieze depicted at least two previously unknown gods in a coronation scene of a Maya ruler, adding to the pantheon of Maya deities and shedding light on coronation practices in this once-powerful empire.

Rosetta Stone, Egypt

The Rosetta Stone was uncovered by French soldiers in 1799 while digging the foundations for a fort. Its inscription, a decree by pharaoh Ptolemy V written in hieroglyphics, ancient Greek and demotic, offered a means to understand ancient Egyptian writing – although it took another 23 years to decipher it. Using the widely-understood ancient Greek text, Egyptologists could make sense of hieroglyphs, allowing them to finally decode all the mysterious inscriptions plastered on temples and buildings across the ancient kingdom. Read Ptolemy V’s proclamation for yourself at the British Museum.

Now discover the beautiful treasures the ancient Egyptians left us

Sponsored Content

Comments

Be the first to comment

Do you want to comment on this article? You need to be signed in for this feature