The incredible story of Tutankhamun’s tomb and its treasures

Tales and treasures from the boy-king’s tomb

The grand opening of the Grand Egyptian Museum has reignited interest in Tutankhamun. He was a pharaoh like no other: a minor during his reign, but mighty after his death. He only ruled for 10 years before his untimely death at age 19, but when his tomb was discovered in 1922 it ignited mysteries that still prevail to this day.

Click through the gallery for the incredible story of that discovery and the compelling treasures it brought to light...

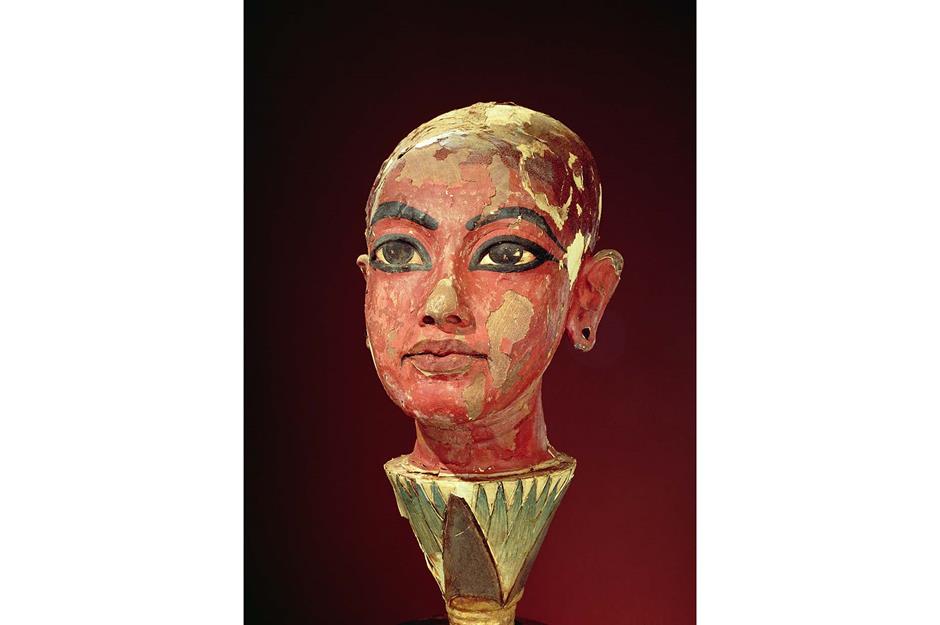

Who was King Tut?

Born around 1341 BC, Tutankhamun, as we know him today, was originally called Tutankhaten. This was in reference to the sun deity that his father, King Akhenaten, ordered the people of Egypt to worship, which was just one of the controversial decisions made during the unpopular king's reign.

However, in Tut's lifetime, his father's rule would be short-lived.

From Tutankhaten to Tutankhamun

Akhenaten died in 1333 BC and at the young age of nine years old, Tut became king. With the help of advisers (one of whom would go on to become his successor), the boy-king reversed many of his father’s controversial decisions.

He moved the royal city from Amarna back to Thebes and returned his people to a polytheistic society (belief in more than one god). He also added ‘amun’ to the end of his name, after the creator god Amun.

Sponsored Content

A forgotten pharaoh

But Tut’s reign wasn't a long one. Just 10 years after becoming king, he died at the age of 19 in 1323 BC and was buried in a relatively small tomb, succeeded by Pharaoh Ay. Despite the changes Tut had made, he was still associated with his father and not remembered too fondly.

In fact, he was largely forgotten about, with sweeping desert sands burying his tomb. But all of that changed centuries later in 1922, when British Egyptologist Howard Carter discovered a step leading to his tomb. And the rest, as they say, is history…

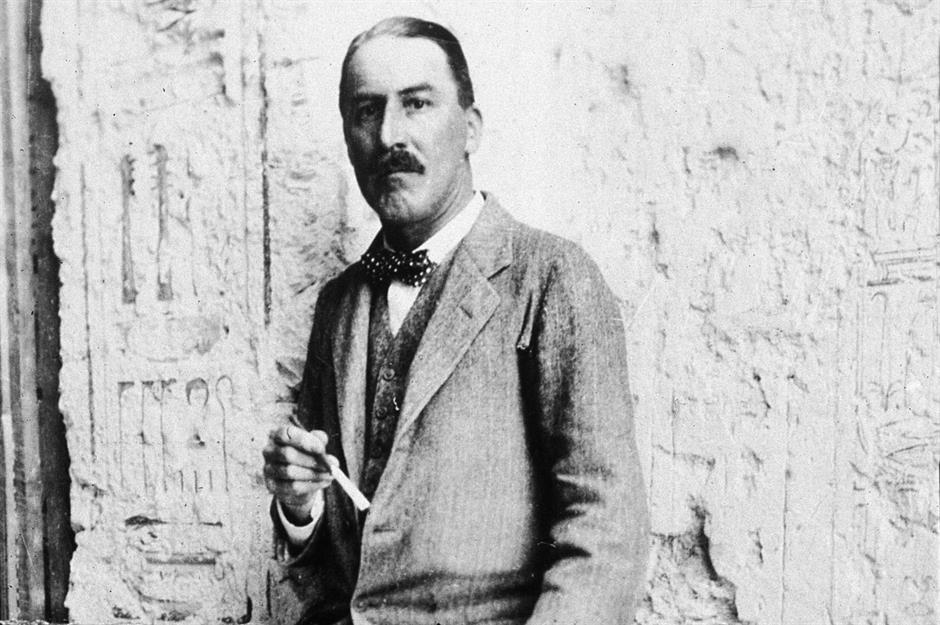

The man, the myth, the Egyptologist

Egypt was under British rule between 1882-1922, which allowed Howard Carter to work on the prestigious Valley of the Kings site in Luxor, where Tut was believed to be buried. After World War I, Carter resumed his search for the royal tomb and on 4 November 1922, a member of his team exposed the first step leading down to the tomb, all by scratching a stick against the sand.

By the end of the next day, the team had uncovered the entire staircase. Little did they know the tremendous quality – and quantity – of treasures that awaited them.

It started with a single step

The step was discovered not far from the entrance of King Ramesses VI’s tomb. It was previously believed that most of the Egyptian tombs in the Valley of the Kings had already been excavated, so its discovery was especially remarkable.

It was even more significant given the timing – Egypt was starting to regain independence from British rule, so it was effectively Carter’s last chance to locate the site. By April 1923, following years of French and British occupation, the country would become the Kingdom of Egypt, with its own constitutional monarchy.

Sponsored Content

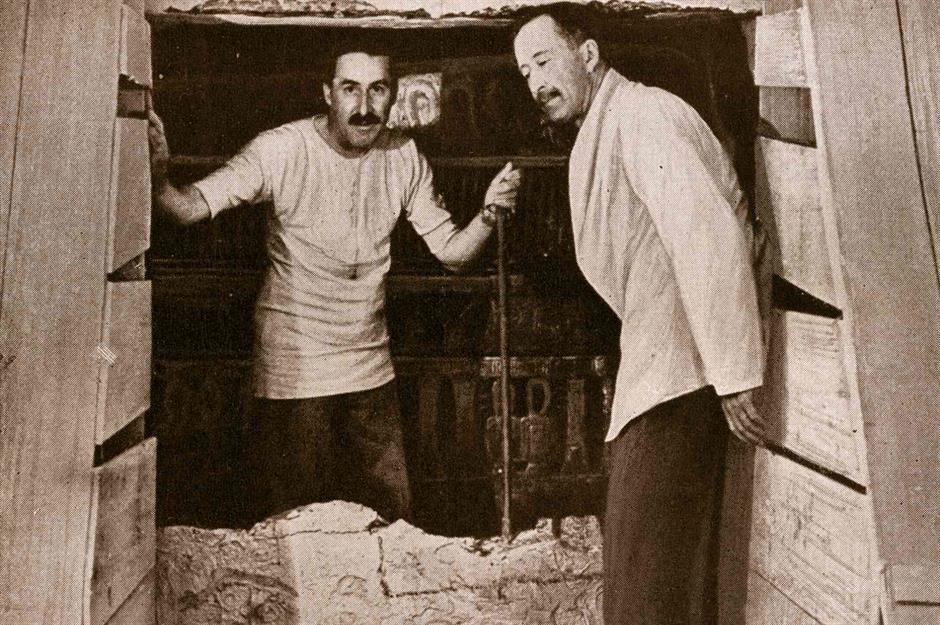

History-changing discoveries

As the month went on, an antechamber, treasury and door to the tomb were discovered. On 26 November, the door – which had remained sealed for 3,245 years – was cracked open.

The room was jam-packed with treasures, although the boy-king’s sarcophagus (a large, coffin-like box displayed on ground level) wasn’t discovered until later on.

Lord Carnarvon’s curse

Ancient Egyptian tombs and pyramids were sacred places, and many believed that a ‘curse of the pharaohs’ awaited anyone who desecrated them. And when Lord Carnarvon, the archaeologist who funded the project and hired Carter, died just four months after first entering the complex, it made the curse seem all too real.

Years later, several hundred Egyptian antiquities (including some from Tut’s tomb) were controversially found in secret cupboards at Carnarvon’s English home, Highclere Castle. Over the years that followed, several other people linked to the excavation died, fuelling a media frenzy about the curse, although Carter himself would live for another 13 years.

Initial excavations

Although encouraged by famous names such as Arthur Conan Doyle, creator of Sherlock Holmes, Carter himself dismissed stories about the curse as “tommy rot” and continued to excavate the four-room tomb undeterred. Over the following months, he and his team discovered an astonishing array of relics including artwork, jewellery, chariots, furniture and weapons.

They were almost packed to the ceiling and it took 10 years to catalogue and empty the tomb, from which they recovered well over 5,000 objects in all.

Sponsored Content

Who’s a pretty boy then?

When Tutankhamun’s sarcophagus was finally discovered, there was no denying who it contained. Within the sarcophagus, three coffins depicted the pharaoh’s portrait as well as Osiris, the god of the underworld.

Beneath these, the legendary funerary mask had been placed over his head. It was made from 22lbs (10kg) of solid gold, as well as lapis, clay, quartz, glass, feldspar and obsidian. His body had been wrapped in resin-soaked bandages and was placed with items to accompany him into the afterlife.

Mummification process

Tutankhamun had been mummified according to ancient Egyptian practice, but even so, a closer examination revealed that he was tall, frail and had an apparent bone disease in his left leg.

The discovery of 130 walking sticks in his tomb added further weight to this theory.

Health and happiness?

The king’s health issues were very likely due to bad DNA. Incest was common among royals in ancient Egypt and although the identity of his mother is still unknown, research has shown that his parents were brother and sister.

Tut himself is believed to have married his half-sister, Ankhesenamun. The couple had two daughters who were both stillborn so there was no direct descendant. Ay, his successor, wasn’t related to Tutankhamun and had been one of his advisors during his reign.

Sponsored Content

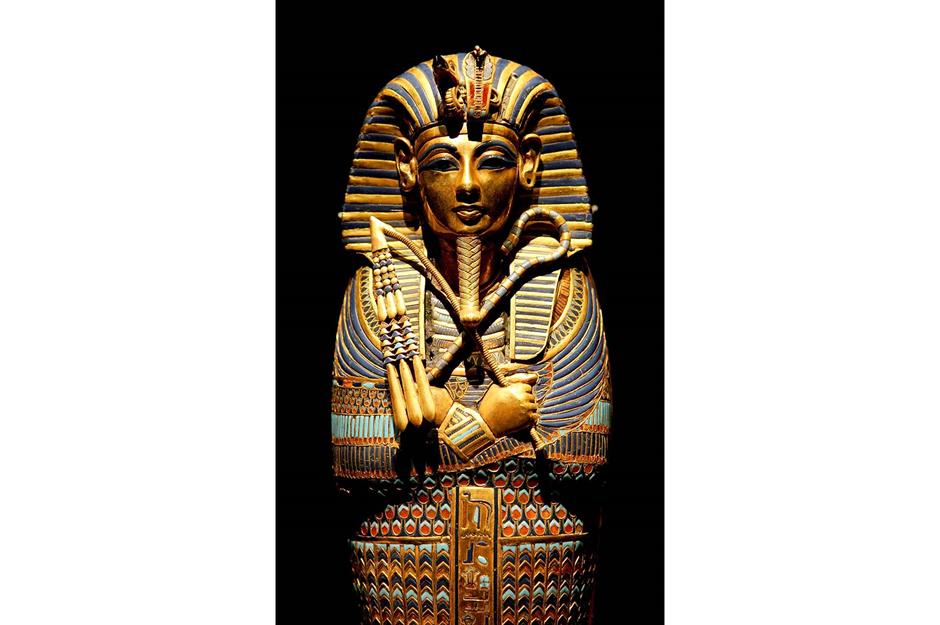

Amazing artefacts

One of the most well-known artefacts from Tutankhamun’s treasure collection is his innermost coffin. He’s depicted as Osiris (the god of the underworld) as he holds a crook (a cane with a hooked handle) and flail (a rod with three beaded strands) which are also symbolic of his kingship.

The coffin was made from solid gold and was anointed in a black resin – Carter described it as a ‘thick black pitch-like layer’ – but it’s now been restored to all its gleaming glory.

Second-hand sarcophagus

This stone sarcophagus may not look as striking as the highly decorated coffins it contained, but there’s more to it than meets the eye. Analysis of its orientation suggests that it was placed in position for a queen (turned to the right from the entrance) instead of a king (which was typically turned to the left).

Some historians now believe it was built for another family member – exactly who is still uncertain, but recent studies suggest that it might have been his stepmother Nefertiti. The tomb’s small size also suggests that Tut’s death was unexpected and the burial rushed, which could explain why this repurposed item was used.

The seated hunt

While seated figures of pharaohs (usually on a throne) were common in funerary contexts, Tut is the only pharaoh to be seen sitting down for physical activities, a nod to his walking difficulties. This fan handle – which held 30 ostrich feathers at the end – portrays an ostrich hunting scene in which Tut is seated in his chariot as he uses the bow and arrow.

The reverse side tells us that the feathers on the fan are from the ostrich he caught during the hunt.

Sponsored Content

Tutankhamun’s throne

This exquisite golden throne was discovered by Carter in the antechamber of Tutankhamun’s tomb. Carved from wood and covered in gold, the inlays and outlays use other materials like silver and semi-precious stones.

This was a common style of royal chairs in the Eighteenth Dynasty. The chair depicts the boy-king with his wife and on each side of the throne are hieroglyphics which say ‘King of Upper and Lower Egypt’.

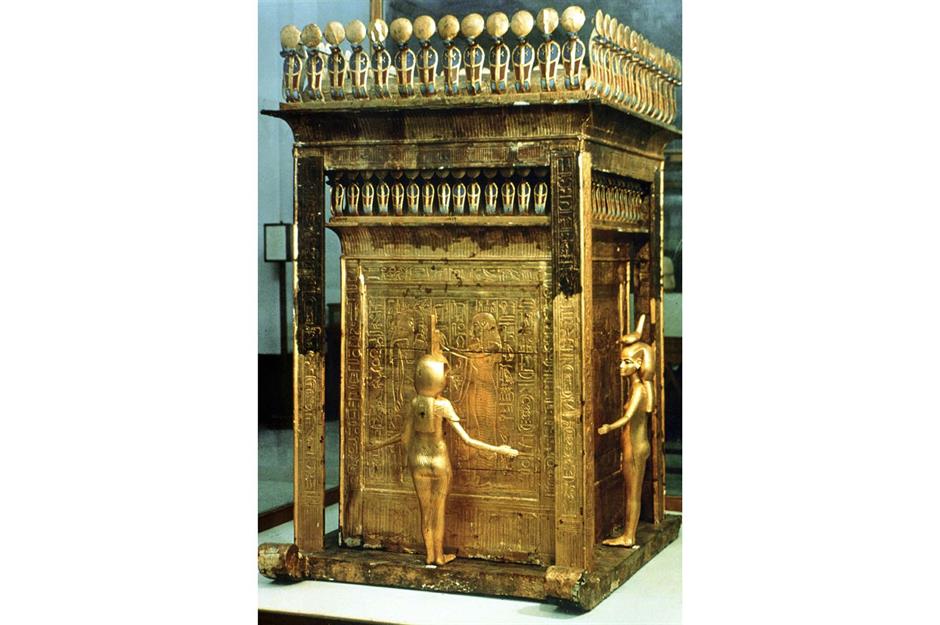

Golden shrines

Tutankhamun’s golden canopic shrine was a 6.5-foot-tall (1.98m) ‘container’ that held the chest of the king’s internal organs. The shrine was made from wood and covered in sheet gold, with each side flanked by a protective goddess with outstretched arms, a detail replicated on the inner calcite chest.

Along the top of the shrine are hieroglyphics topped with cobras wearing gold sun disk crowns, while pictures on each side of the shrine depict scenes of Tutankhamun’s daily life with his queen.

Detailed jar stoppers

Organ removal was part of the mummification process and included the embalming of the lungs, liver, stomach and intestines. The heart was left in place as it was believed it was needed for the afterlife. These calcite lid-toppers were used for the jars that contained the king’s internal organs.

Usually four jars were contained in one chest, as pictured here. They were protected by the figures of four goddesses on each corner of the chest, each with outstretched arms.

Sponsored Content

Valuable coffers

Another item discovered in the tomb was this beautiful, square-shaped coffer (a large stone-shaped chest). The relic is made from wood and ivory with applied gold and silver, and is covered in hieroglyphics.

Along with other chests found in the tomb, they generally contained personal items such as jewellery, sandals and embroidered ceremonial robes.

Footwear

Around 80 to 90 pairs of sandals were found in Tut’s tomb. During the mummification process, his feet would have been thoroughly washed first before a pair of sandals were placed on his feet, followed by linen bandages.

This photograph shows a replica of a pair recovered from his tomb. On each side are figures and arches that represent Egypt’s nine traditional enemies, which the pharaoh symbolically trod on.

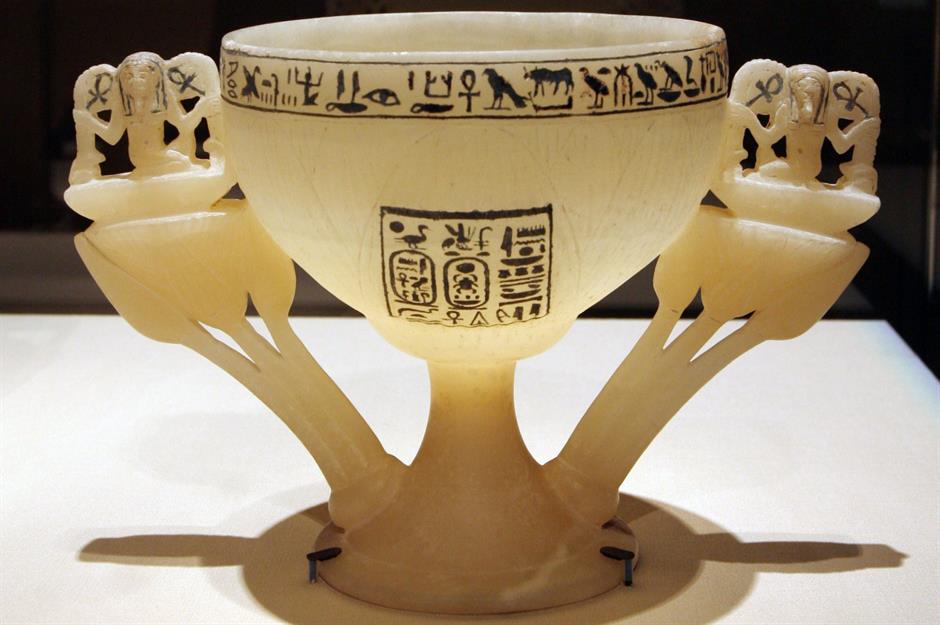

Powerful words

This alabaster cup was one of the first relics Carter found in the tomb’s antechamber. The lotus blossom-shaped cup is also known as the Wishing Cup – as named by Carter – as the hieroglyphics around the rim wish for a long life for the king’s ka (spirit).

Tut’s name is on one side of the cup and a small figure of the god Heh is on each handle.

Sponsored Content

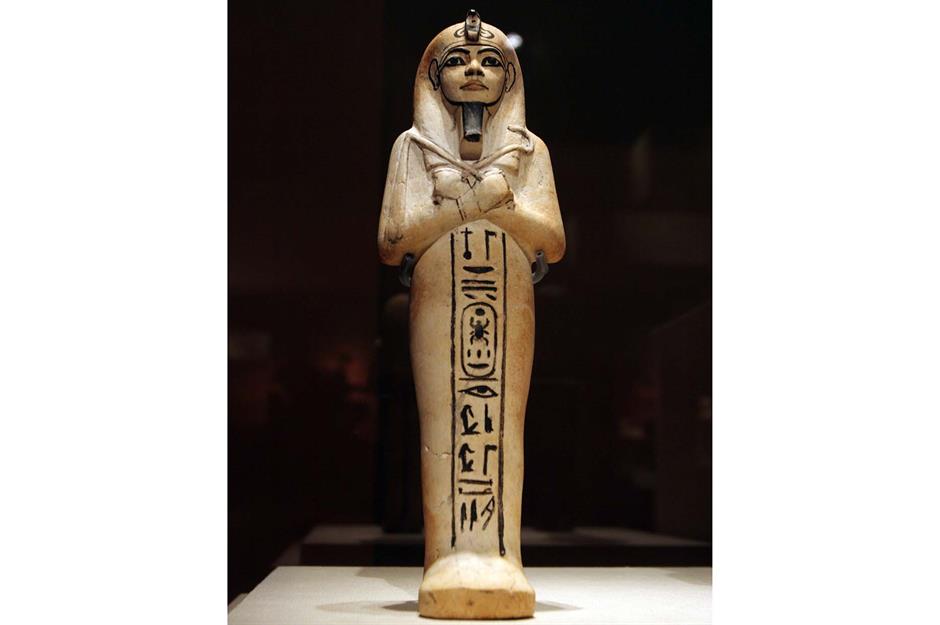

Special shabtis

This funerary figurine, or shabti, depicts Tutankhamun holding the crook and flail to represent Osiris, the god of the underworld. The hieroglyphics include royal epithets and the king’s throne name, Nebkheperure.

An incredible 413 shabti were discovered inside Tut’s tomb, reflecting his royal status, whereas most private burials only included two. Shabti were believed to perform tasks for the deceased in the afterlife and scrolls were often included instructing them to perform their duties.

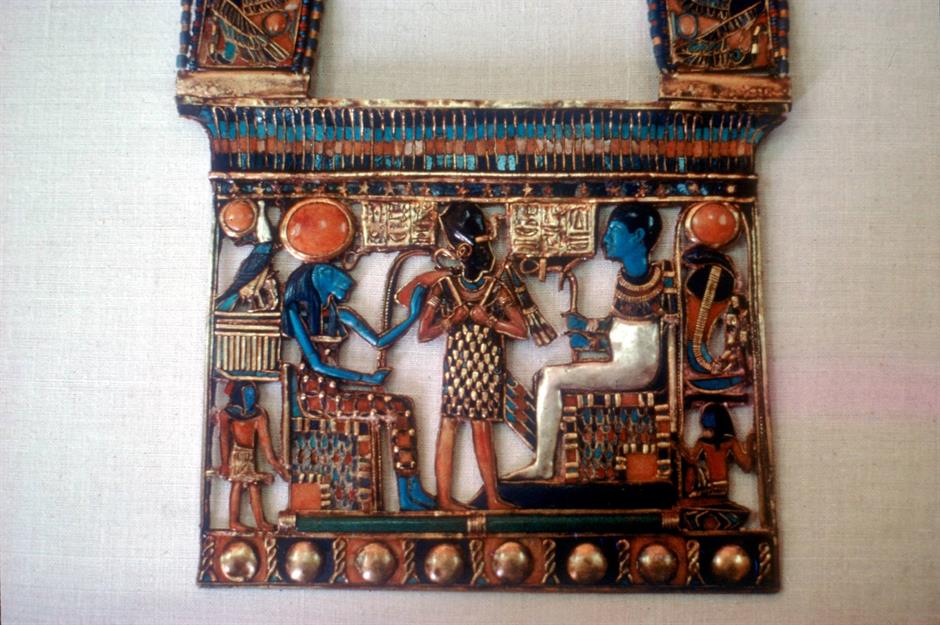

Royal jewels

One of the most ornate pieces of jewellery discovered was this pectoral jewel. It depicts Ptah, the creator of the universe and patron of craftsmen, with his consort Sekhmet, the lion-headed goddess of war.

In between the two of them stands Tutankhamun, who is dressed in full pharaoh regalia. This piece would have been worn like a brooch by the king. Many other intricately detailed pectoral jewels were also found in the tomb.

Very old vessels

Other objects located in the tomb included small jewellery chests, miniature shaped vessels and even a games board. The larger vessel pictured here was one of two of this type out of the 80 vessels found. It still contained an oily residue when it was excavated and although research revealed it to be a mixture of coconut oil and frankincense, its use is still unknown.

This vessel was made from calcite and was decorated in a faience (glazed ceramics) style, the blue and green colours representing rebirth. The faience style was a feature of other Egyptian funerary chambers, like the Djoser Pyramid in Saqqara.

Sponsored Content

From painstaking hand restoration…

The restoration lab of Giza’s Grand Egyptian Museum (which opened in November 2025) has painstakingly worked on delicate items like this wooden and gold-covered chariot. The tangled pieces of six dismantled chariots were discovered in the antechamber and north wall of the treasury.

Chariots weren’t a common inclusion in funerary contexts, and only a few have been found in other pharaohs’ tombs. It was more common for them to be depicted in art, to represent the king’s association with battle and domination.

…to myth-busting modern technology

Thanks to modern technology, researchers have gained a deeper insight into Tut’s health issues and the cause of his death. In 2005, a CT scan showed that he had a broken left leg that became infected, while DNA analysis confirmed he had malaria. It’s now widely believed that one of these (or both) led to his death.

While radar testing once disproved the theory that Nefertiti (his predecessor) was buried in the same place as the boy-king, Egyptologist Nicholas Reeves recently suggested there are still clear traces of a previous name on the north wall, perhaps suggesting that the famous queen lies hidden in a burial chamber nearby.

New beginnings

The Grand Egyptian Museum's restoration lab has been working hard in recent years on many objects, including King Tut's golden coffin (pictured here). The restoration process was no easy feat, with extensive studies, tests and digital imaging taking place before any work could even commence.

The lab is entrusted with the preservation of over 100,000 artefacts, ensuring they are safeguarded for future generations. Other items from Tut’s tomb that have been restored by the lab include beds, pottery, jewellery and a scarf.

Sponsored Content

The boy-king today

Although much delayed, the Grand Egyptian Museum finally opened its doors to the public in November 2025. Twice the size of the Louvre, it includes two halls dedicated to Tutankhamun – the first time that the entire collection of 5,398 Tut-related objects has ever been exhibited together.

Spread over 75,347 square feet (7,000sqm), the display includes his famous mask, gilded sarcophagus, throne and many other treasures. The only major exception will be his mummy, which is still on display in its stone sarcophagus, surrounded by beautiful murals, in the Valley of the Kings.

Controversy in the closet

While a large number of Tut's treasures are still in Egypt, others are on display at the British Museum. In 1988, the seventh Earl of Carnarvon (Lord Carnarvon's grandson) discovered over 300 ancient Egyptian treasures – including some of Tut's – stashed away in hidden cupboards at Highclere Castle.

It seems that the sixth Earl of Carnarvon (his father) had lost a lawsuit with the Egyptian government in 1924 for a half share of the tomb's treasures and possibly hid his collection from view. Controversially, a number of these ancient artefacts are still on display at the castle today.

Now see inside Egypt's 'Lost Golden City' only recently discovered

Comments

Be the first to comment

Do you want to comment on this article? You need to be signed in for this feature